Regular physical activity and exercise are necessary for optimal health and development in children. This is especially true for children with juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA), where joint swelling, pain, stiffness, and fatigue often result in a sedentary lifestyle and poor fitness. Despite remarkable advances in the pharmacological management of joint inflammation, many children with JIA—even those whose disease is well-controlled or in remission—have significant impairments of aerobic and anaerobic exercise capacity.1-3 Deficits may begin early in the disease course, continue into the adolescent and young adult years, and persist long after clinical remission. While daily energy expenditure in children with JIA appears to be similar to that of healthy children, their participation in vigorous physical activity and sports is considerably less. As a result they often fail to develop the strength, endurance, gross motor skills, and neuromuscular control that are necessary for safe and enjoyable participation in recreational sports. Children with mild arthritis who do play sports may get injured because they are poorly conditioned or have impaired neuromuscular function.4

What Exercises Are Best?

A growing body of literature suggests that a comprehensive physical conditioning regimen may be safe and beneficial for most children with JIA.3-6 The exercise medium (water or land) is less important than the intensity, duration, and frequency of the exercise sessions and the overall length of the program; a minimum of two 30 to 60 minute sessions of general conditioning each week for at least eight weeks is necessary to induce improvements in fitness and functional capacity.

When planning an exercise program for a child with arthritis, there are three main questions to consider:

- When should a child with arthritis be referred to physical therapy (PT) for an exercise regimen?

- What constitutes a safe and effective exercise prescription for a child with arthritis? and

- What is the most effective strategy to insure the child’s adherence to the exercise program?

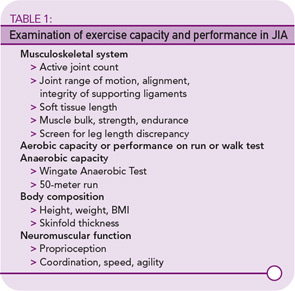

I believe that children with JIA, especially those with polyarticular disease, should be referred to PT early in the disease course so that the therapist can examine the child’s aerobic and muscular exercise capacity; document any biomechanical impairment in joint mobility, alignment, or integrity; and establish functional goals that are important to the child or parents. (See Table 1, TK, for components of the PT examination.)

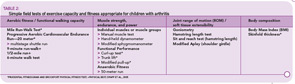

While some children may require controlled laboratory tests of exercise capacity (VO2peak), the majority only need field tests of aerobic and muscular performance. Table 2 lists fitness tests that are generally safe and appropriate for children with arthritis and easily performed in the clinic or school setting. The Prudential FitnessGram, Physical Best, and Brockport Physical Fitness Test provide health fitness standards that are compatible with good health and prevention of the chronic diseases associated with a sedentary lifestyle. These test batteries also include training programs and software to track a child’s progress.

Exercise Prescription

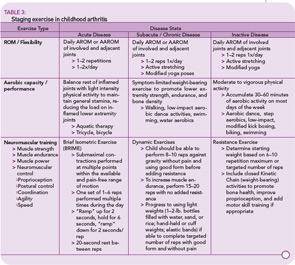

Balanced rest and exercise are necessary to manage pain and maintain joint mobility and function. Table 3 illustrates the components of a general physical conditioning program. The individualized exercise prescription for a child with JIA should be graded to the child’s disease status and initial fitness level. During periods of acute arthritis, the goal is to prevent loss of motion and preserve normal alignment and integrity of the involved joints, while maintaining functional capacity. Daily active range of motion (AROM) or active–assisted range of motion (AAROM) exercises should target joints with active disease, as well as adjacent joints that are at risk for secondary loss of motion. The Arthritis Foundation book, Raising a Child with Arthritis: A Parent’s Guide, includes instructions and illustrations for ROM and postural exercises. I recommend doing ROM exercises during or after a warm bath or shower before bed to relax the child for sleep and reduce morning stiffness. Submaximal isometric contractions performed at multiple points in the pain-free ROM may preserve muscle bulk and strength during the acute stage. The child should also be encouraged to accumulate at least 30 minutes a day of low intensity aerobic activity that does not stress inflamed joints—for example swimming, walking in a warm pool, or riding a bike.

During subacute and chronic stages, AROM should continue, and the PT can also teach the child to perform gentle active stretches to lengthen shortened tissues. Encourage dynamic strengthening exercises; external resistance in the form of light hand or cuff weights or elastic bands can be added once the child is able to perform eight to 10 repetitions of the exercise against gravity without pain while maintaining good form. The amount of resistance is determined by the initial assessment of the child’s six to 10 repetition maximum, and should be increased when the child can perform sufficient reps with the current load. Encourage moderate intensity weight-bearing aerobic activities to improve fitness, build strength, and promote good bone density. Encourage parents to set aside exercise time and exercise with their child to improve adherence.

Many children whose disease is well-controlled or inactive want to play a sport. A PT can help the child choose a sport that matches his or her abilities and interests and develop a training program to remediate deficits in strength, endurance, motor skills, and neuromuscular control, thereby reducing the risk of injury (See fig. 1). Low impact drills that challenge movement speed, agility, and coordination add interest to a conditioning regimen. Finally the child should be taught how to recognize the signs of overuse, use RICE (rest, ice, compression, elevation) for pain and swelling, and modify his or her activities to reduce stress to the joint.

Dr. Klepper is assistant professor of clinical physical therapy at Columbia University, College of Physicians and Surgeons in New York City.

References

- Klepper SE. Exercise and fitness in children with arthritis: evidence of benefits for exercise and physical activity. Arthritis Care Res. 2003;49:435-443.

- Lelieveld OT, van Brussel M, Takken T, et al. Aerobic and anaerobic exercise capacity in children with juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Arthritis Care Res. 2007;57:898-904.

- Van Brussel M, Lelieveld OT, van der Net J, et al. Aerobic and anaerobic exercise capacity in children with juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Arthritis Care Res. 2007;57:891-897.

- Myer G, Brunner HI, Melson PG, et al. Specialized neuromuscular training to improve neuromuscular function and biomechanics in a patient with quiescent juvenile rheumatoid arthritis. Phys Ther. 2005;85:791-802.

- Singh-Grewal D, Wright V, Bar-Or O, Feldman BM. Pilot study of fitness training and exercise testing in polyarticular childhood arthritis. Arthritis Care Res. 2006;55:364-372.

- Epps H, Ginnelly L, Utley M, et al. Is hydrotherapy cost-effective? A randomized controlled trial of combined hydroptherapy programmes compared with physiotherapy land techniques in children with juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Health Technol Assess. 2005;9:1-59.

- American Physical Therapy Association. Guide to Physical Therapist Practice, 2nd Edition. APTA, Alexandria, Va.; 2001.