nukeaf / shutterstock.com

In 1866, Adolf Kussmaul, an internist, and Rudolf Maier, a pathologist, published the classic characterization of what eventually became known as polyarteritis nodosa.1 It was the first scientific clinical characterization of a noninfectious vasculitis. As such, it became a paradigmatic point of contrast to other types of vasculitides that were later described. Their description also provided key information about vasculitides that are still used to evaluate patients. Incorporating both precise clinical acumen and the latest in scientific technologies, the case continues to be a source of inspiration and guidance to today’s rheumatologists.

The New Scientific Era of Medicine

To understand the importance of the Kussmaul and Meier case, it is important to place it in the scientific context of the era. Eric Matteson, MD, MPH, is a professor of medicine in the divisions of rheumatology and epidemiology at the Mayo Clinic, in Rochester, Minn. One of Dr. Matteson’s interests is the history of medicine, particularly as it relates to rheumatology. “I think this medical history teaches us how we came to know what we know, and I think that’s important,” he explains. “It also shows us how difficult it is. That helps us know how medicine has advanced and was made more scientific and, ultimately, led to better understanding of the disease and its treatment.”

This was an era in which scientific medicine was first being developed. Various procedures had been performed for hundreds of years, such as removing cataracts, setting wounds, performing amputations and lancing boils. But various superstitions, dubious potions and erroneous metaphysics existed alongside these practices. The scientific basis of disease did not start to become systematically explored until the 1800s or late 1700s.

“Our understanding began to improve with systematic teaching of anatomy initially, and then systematic teaching of pharmacology,” recounts Dr. Matteson. “Then came the advent of technologies like the microscope, the stethoscope and also some chemical analyses of different substrates, like urine.” Clinicians began bringing these tools into their clinical practice.

Diseases of the blood vessels have been known since antiquity, but inflammatory arterial disease had not been characterized. At the end of the 18th century, John Hunter made some of the first observations about diseases of inflammation associated with blood vessels in his observations on phlebitis.

Karl Rokitansky likely provided a description of a case of polyarteritis nodosa in 1852. Although he provided a compelling pathological description of aneurysmal findings seen in autopsy, it was only years later that one of his students examined the specimens under the microscope and found the characteristic changes of inflammation. Rokitansky mistakenly thought the changes were degenerative or hereditary in nature.

There are other earlier cases we can now recognize as probable vasculitis, based on autopsy reports.2 Dr. Matteson points out, “The introduction of the more scientific methodology and reasoning and technology really helped revolutionize our understanding of disease. The Kussmaul and Meier case is really a watershed in rheumatology for that reason.”

‘I think this medical history teaches us how we came to know what we know, & … that helps us know how medicine has advanced & was made more scientific &, ultimately, led to better understanding of the disease & its treatment.’ —Dr. Matteson

The Kussmaul & Meier Case

Kussmaul and Meier published the first characterization of polyarteritis nodosa in the inaugural journal of German Archive of Clinical Medicine: “On a previously undescribed peculiar arterial disease (Periarteritis nodosa), accompanied by Bright’s disease and rapidly progressive general muscle weakness.”1 The first of the clinical cases described is that of Carl Seufarth, a 27-year-old journeyman tailor hospitalized in Freiburg, Germany. Kussmaul and Maier first speculated the disease might have been caused by a human form of nematode infection similar to Strongylus, and even published an initial abstract to this effect.3 However, the two withdrew this impression in their subsequent full report of the case.1

Seufarth appeared quite ill on first contact. Kussmaul and Meier described Seufarth as “[one] of these patients for whom one can already give the prognosis before the diagnosis. The first impression was of a lost soul whose … days were numbered.” The patient’s symptoms seem to have begun a month or more earlier. Seufarth developed acute signs and symptoms of recurrent fevers, tachycardia, decreasing appetite, severe thirst, global myalgias, mononeuritis multiplex, abdominal pain (with occasional vomiting and diarrhea alternating with constipation), proteinuria and modest lymph node swelling. Kussmaul and Meier also described a sign characteristic of vasculitis: “small nodular tumors in the subcutaneous tissue of the chest and abdomen.”1,4

The authors’ description of Seufarth’s rapidly advancing mononeuritis multiplex (secondary to his vasculitis) is particularly vivid. Seufarth was admitted with a minor neurological deficit including numbness of the thumb and neighboring two fingers of the right hand. This rapidly worsened.

“In the next days the general weakness increased so rapidly that he was unable to leave the bed, [and] the feeling of numbness also appeared in the left hand.” The paralysis progressed quickly but inconsistently. “Before our eyes a young man developed a general paralysis of the voluntary muscles, which, accompanied by severe muscle pains, progressed so rapidly, that the patient was already bedbound after a few days, had to be fed by the attendants, and within a few weeks was almost completely robbed of the use of most of his muscles.”1,2

Seufarth’s symptoms advanced quickly over his 30-day hospitalization, ultimately leading to his death. With the therapeutic tools then available, there was little that Kussmaul could do as treating physician. The authors described Seufarth on the day before his death: “The patient was in a state of extreme weakness. He was scarcely able to speak, lay with persistent severe abdominal and muscle pains, opisthotonically stretched, whimpering, and begged the doctors not to leave him.”1,4

Throughout his illness, the treating clinicians were quite puzzled by the patient’s presentation. Seufarth’s illness could not be fitted into any previously defined clinical picture. “We deemed it wise to forego a diagnosis,” the authors noted. “It was either an unusually complicated trichinosis, or must be an altogether still little known, or unknown illness. It is understandable that under these circumstances, we awaited the results of the autopsy with great anticipation.”1

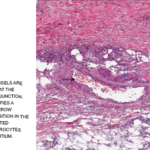

The autopsy report revealed unusual findings of visible nodules along medium-sized arteries. “One glimpse of the transected muscles … immediately demonstrated something unusual … numerous, whitish small tumors up to the size of poppy seeds and hemp seeds.”

Kussmaul and Meier described, “peculiar mostly nodular thickening (periarteritis nodosa) of countless arteries of and below the caliber of the liver artery and the major branches of the coronary arteries of the heart, principally in the bowel, stomach, kidneys, spleen, heart and voluntary muscles, and, to a lesser extent, also in the liver, subcutaneous cell tissue, and in the bronchial and phrenic arteries.” Kussmaul and Meier suggested the term periarteritis nodosa, due to this nodular thickening over blood vessels and the perceived localization of the inflammation to the perivascular sheaths, media and outer layers of the arterial walls.1,4

Now, many other techniques are available to the astute clinicians, including techniques from molecular biology, gene sequencing & detailed medical imaging. Yet when not paired with careful clinical observations, such tests can sometimes lead us astray.

The Paradigmatic Vasculitis

The disease served as a reference point for forms of noninfectious idiopathic vasculitis that were subsequently identified. Its research led to breakthroughs in understanding the pathophysiology of other forms of vasculitis. Dr. Matteson notes, “This description was a really important moment because it became a comparator for other forms of vasculitis that were subsequently described.” Other forms were characterized in terms of their similarities or differences to the constellation of signs, symptoms and pathological findings.5

In the decades to follow, most forms of vasculitis were termed periarteritis nodosa. Even early cases of Kawasaki disease were initially labeled “infantile periarteritis nodosa.” In the early 1900s, the term polyarteritis nodosa began to replace periarteritis nodosa, to emphasize the fact the lesions were found to be transmural and the fact that multiple arteries were affected.4

It eventually became recognized that the term polyarteritis nodosa actually included a wide group of clinically distinct syndromes. “In the 1920s, microscopic polyangiitis was first described, and that could be set apart from the Kussmaul case because it involved very small blood vessels and was associated with lung hemorrhage and glomerular nephritis,” Dr. Matteson explains.

Other examples include the description of a vasculitis associated with asthma and small vessel disease in the teens and ’20s—eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (EGPA, formerly Churg-Strauss syndrome). The 1930s saw identification of another form of vasculitis: giant cell arteritis, which was also clearly different in the organs it involved compared with Kussmaul’s case.

Other types of vasculitides continued to be identified.

Current Vasculitis Nomenclature

Over the years, classification of vascular diseases evolved. The first coherent vasculitis scheme was compiled in 1952 by the pathologist Pearl Zeek, which then served as a benchmark for later systems.6 “What we use now is the 2012 Chapel Hill nomenclature,” says Dr. Matteson. “It is actually going to undergo some further modification in the next year or so because we have continued to make progress in our understanding of these diseases.”7

Defining these different subsets is helpful both for establishing prognosis and developing more specific effective therapeutic choices.

As defined by current nomenclature, only a very small subset of vasculitides is now categorized as polyarteritis nodosa. A diagnosis of polyarteritis nodosa is now applied to multisystemic necrotizing arteritis that does not otherwise fit into a currently recognized vasculitic syndrome.2,8

“We still see polyarteritis nodosa, but many of the other forms of vasculitis are much more common,” notes Dr. Matteson. “One of the thoughts is that that portion of polyarteritis that might be linked to hepatitis B may be declining. That may be a contributor to why that disease is a lot less common than some of other vasculitides.”

There are still many important questions remaining around vasculitides in general. “I think the most important questions around vasculitis are around pathogenesis: how they get started, what triggers them, and what conditions in the body and the immune system favor their expression.”

Dr. Matteson likens the situation to the conditions in a forest. “There are lots of ways to set fire to a forest. But whether your forest catches on fire really depends a lot on the conditions. Is it dry, are the trees close together, is there a lot of brush, is there a lot of wind, or has it not rained for a long time? If all those conditions are there, your forest is going to take off like wildfire.”

Innovations in treatment are another important ongoing research avenue. Dr. Matteson notes that in some cases, our therapeutic choices have actually given clinicians better understanding of disease. “A great example is granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA). There was an idea by some clinicians to use rituximab, a B cell inhibitor, to treat GPA, even though there was no evidence that B cells had any involvement in this disease. We didn’t know that.” In this case, the treatment innovation worked. He continues, “Subsequently we’ve gotten better ideas about why that might be the case, and that has given us some insights into the pathophysiology of the disease.”

General Principles of the Case That Still Apply

Dr. Matteson believes the Kussmaul and Meier article demonstrates some important principles that are important to rheumatologists (and other clinicians) moving forward. “The case shows us how we can go wrong if we have fixed ideas about disease.”

He notes that Rokitansky’s description of a clinical case of polyarteritis nodosa predates that of Kussmaul and Meier, but Rokitansky failed to recognize it. “Part of the reason he failed to understand the nature of the disease is that he was not fond of using the microscope, which was actually available even in 1850.”

One of his students later identified the disease based on histological findings. Dr. Matteson notes that Dr. Rokitansky had preconceived notions about what blood vessel disease was. “I think that understanding cases like the Kussmaul case actually provides us with some humility, because we see that there are errors in thinking that are made by very smart people. I think that is important.”

The case also highlights the important role that clinicians can play in recognizing disease associations that ultimately better define diseases and lead to better therapeutics. Kussmaul was an astute clinician, and it was partly his attention to clinical detail that allowed him to successfully characterize the first case of non-infectious vasculitis. Dr. Matteson points out other historical examples of clinicians making such important observations, such as the identification of Helicobacter pylori in the pathogenesis of stomach ulcers, and the many insights of AIDS that were first made by clinicians working directly with patients. “Today there is still lots of opportunity for the clinicians to make important contributions in identifying diseases,” he notes.

Of course, since Kussmaul and Meier’s time, a wide range of clinical diagnostic tools has become available. As Dr. Matteson points out, “They didn’t have X-ray; they didn’t have angiogram—the only thing they could do was an autopsy.” Now, many other techniques are available to the astute clinician, including techniques from molecular biology, gene sequencing and detailed medical imaging. Yet when not paired with careful clinical observations, such tests can sometimes lead us astray.

Today’s rheumatologists deal with many diseases that are obscure or difficult to diagnose and recognize. Importantly, Kussmaul paired his willingness to use new scientific technology with a sharp clinical acumen. Such a pairing is critical for rheumatologists, who must often utilize subtle clinical signs and symptoms along with sophisticated testing to formulate diagnoses and treatment plans.

Although it has been over 150 years since its initial publication, Kussmaul and Meier’s description still provides a powerful example of how to combine these two essential approaches.

Ruth Jessen Hickman, MD, is a graduate of the Indiana University School of Medicine. She is a freelance medical and science writer living in Bloomington, Ind.

References

- Kussmaul A, Maier R. Ueber eine bisher nicht beschriebene eigenthümliche Arterienerkrankung (Periarteritis nodosa), die mit Morbus Brightii und rapid fortschreitender allgemeiner Muskellähmung einhergeht. Deutsche Arch klin Med. 1866:1;484–518.

- Matteson EL. Historical perspective of vasculitis: Polyarteritis nodosa and microscopic polyangiitis. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2002 Feb;4(1):67–74.

- Kussmaul A, Maier R. Aneurysma verminosum hominis: Vorläufige Nachricht. Deutsches Arch klin Med. 1866;1:125–126.

- Stone JH. Polyarteritis nodosa. JAMA. 2002 Oct 2;288(13):1632–1639.

- Matteson EL. Classical descriptions of vasculitis—what do they teach us in the 21st century? Rev Series Rheumatol. 2003;1:4–9.

- Zeek PM. Periarteritis nodosa: A critical review. Am J Clin Pathol. 1952 Aug;22(8):777–790.

- Jennette JC. Overview of the 2012 Revised International Chapel Hill Consensus Conference Nomenclature of Vasculitides. Clin Exp Nephrol. 2013 Oct;17(5):603–606.

- Hernández-Rodríguez J, Alba MA, Prieto-González S, et al. Diagnosis and classification of polyarteritis nodosa. J Autoimmun. 2014 Feb–Mar;48–49:84–89.