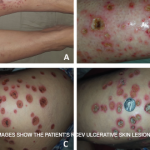

Current guidelines are inadequate to incorporate vasculitic syndromes involving skin.

Clinical Photography, Central Manchester University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, UK / Science Source

CHICAGO—Warren Piette, MD, professor of dermatology at Rush University Medical Center, Chicago, updated rheumatologists on the topic of cutaneous vasculitis at the ACR’s State-of-the-Art Clinical Symposium in April. He began by explaining that the current vasculitis criteria developed by the ACR in 1990 and the Chapel Hill Consensus Conference (CHCC) in 1994 are inadequate to incorporate vasculitic syndromes involving skin. This deficiency has led an international group to propose revised criteria that will soon be submitted to Arthritis & Rheumatology.

Dr. Piette focused his talk on immune complex vasculitis and anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic autoantibody (ANCA)-associated vasculitis and the purpura that are key to their diagnosis. He explained that purpura can be primary or secondary, and distinguishing the two clinically is more art than science. He emphasized the importance of lesional morphology in sorting purpura pathophysiology into simple hemorrhage, inflammatory hemorrhage or microvascular occlusion, and he also disputed a few dogmas.

Primary Palpable Purpura Are Not Specific for Vasculitis

Primary palpable purpura are not specific for vasculitis. Moreover, explained Dr. Piette, vasculitis is not always palpable or purpuric. He then showed a series of slides of purpura and talked the audience through their diagnoses.

He emphasized the importance of determining if the lesion is blanchable. If the early lesion completely blanches, then it is not purpura, although it could still be vasculitis. If the early lesion partially blanches, then the patient likely has inflammatory purpura, but does not necessarily have vasculitis. Finally, if a lesion doesn’t blanch, then it could simply be a hemorrhage.

Dr. Piette described the four main purpura patterns—multi-generalized, acral, pauci-random and multi-dependent—and showed examples of each. He also noted that there is an evolving recognition that retiform purpura is also a typical morphologic pattern of cutaneous vascular occlusion. Multi-generalized purpura generally contain fewer than 100 lesions, distributed widely and often randomly. They are usually caused by a virus or drug and are only rarely urticarial vasculitis, lymphomatoid papulosis (LyP) and pityriasis lichenoides et varioliformis acuta PLEVA/Lyp, or bowel stasis vasculitis. If the patient with multi-generalized purpura is very ill, however, with multiple lesions retiform, Dr. Piette suggests that purpura fulminans be considered as a diagnosis.

Acral purpura tend to locate on the hand and/or foot. These stocking-glove purpura are likely caused by viral infection, especially parvovirus infection. They may also be caused by sepsis/disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) with hypotension leading to microvascular occlusion in vasoconstricted areas. Patients who have retiform purpura in cold-exposed areas, such as ears, nose, hands and feet, likely have cryoglobulins, cryofibrinogens and/or cold agglutinins.

Dr. Piette described pauci-random purpura as fewer than 25 lesions distributed randomly over the body, with occasional clusters on the legs. They are typically formed as a result of ANCA-associated vasculitis or microvascular occlusion, and only rarely are they the result of PLEVA/LyP.

Multi-dependent purpura patterns tend to include more than a 100 purpura. If they are not palpable or partially blanchable, then they are likely caused by platelet-related simple hemorrhage, immune complex vasculitis, or benign hypergammaglobulinemic purpura of Waldenstrom, or are chronic pigmented purpura. If the multi-dependent purpura are palpable or partially blanchable, they probably result from immune complex vasculitis or, more rarely, are chronic pigmented purpura. Purpura that are palpable or partially blanchable may be the result of a disease with secondary hemorrhage.

Dr. Piette described the four main purpura patterns—multi-generalized, acral, pauci-random & multi-dependent—& showed examples of each.

Vasculitis Can Mimic Both Simple Hemorrhage & Occlusion

Dr. Piette explained that vasculitis can mimic both simple hemorrhage and occlusion at the clinical and histological level. He then presented slides of purpura and discussed whether the patient had vasculitis, hemorrhage or occlusion. He first presented a patient who had a recurrent crop of lesions that were predominantly macular. Dr. Piette explained that if the purpura burn and occasionally itch, then the patient may have benign hypergammaglobulinemic purpura of Waldenstrom. Such purpura often follow exercise or the ingestion of aspirin or alcohol. They are most common in younger women with no systemic findings.

Urticarial vasculitis also tends to burn more than it itches, and the lesions last longer than 24–48 hours. In this case, the purpura are often minimal and are idiopathic. Urticarial vasculitis may be associated with hepatitis B and hepatitis C infection, as well as systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). In the case of urticarial vasculitis, history is often more important than biopsy. Consequently, it may be helpful to circle the lesions in order to determine lesional duration. Patients with urticarial vasculitis who have systemic disease or are hypocomplementemic may benefit from a check for C1q antibody.

Conclusion

Dr. Piette explained the initial evaluation of purpura can be done from the doorway. Closer inspection should reveal the morphology of the purpura. The number, distribution and morphology shape the clinical hypothesis. When the data are put together, the physician should be able to propose whether the patient has a simple hemorrhage, inflammatory hemorrhage or occlusion. This clinical hypothesis should then be correlated with additional clinical and laboratory data. He noted, though, that histologic and immune findings can be misleading if the age of the biopsied lesion is not considered in the diagnosis.

Lara C. Pullen, PhD, is a medical writer based in the Chicago area.