In the second week of April–a time in Durham when green-yellow buds burst forth from barren branches, the birds tune up their summer songs, and azaleas flash with magenta and pink–our division finished its interview season for fellows for next year. By all indications, 2012 will be a banner year. The applicants we interviewed were uniformly bright, motivated, and enthusiastic. I would be happy to have any one of these fine young people join our program. Whoever comes to Durham, we will do our best to teach them the fine points of rheumatology. We will also teach them about motion offense and man-to-man defense for those who live under a rock and do not know Atlantic Coast Conference basketball.

Like all young people applying for positions these days—medical school, house staff, fellowship—our applicants were uniformly well dressed. Dark suits are clearly de rigueur for men and women alike. Such an outfit clearly signifies seriousness—indeed, solemnity—of purpose. That’s OK. Program directors like seriousness. No wild and crazy guys (or gals) for us, and we appreciate that you care what we think. As they say, you have only one chance to make a first impression, and the first impression has been very good.

An Abundance of Seriousness

Nevertheless, I do have concerns about all that dark wool that clothed our applicants and made them look like clergy. A dark suit is certainly safe, but since I grew up in era when great flannel meant conformity and a dreary and stunted spirit, I like some expression of individuality. My recommendation for the class of 2013 applicants is therefore to lighten up. Add a little color. Make a splash. I guarantee that I will remember you much better if you wear an orange polka-dot tie than a plain-Jane blue and red foulard that Brooks Brothers sells in airports. I anticipate that once interview season is over, the black, blue, or pinstripe suits will go back into the closet and not be seen again until job-hunting time a few years hence.

In my discussions with the current applicant pool, I have been very gratified by their understanding of rheumatology. They seem to grasp the essence of our specialty because, at their core, physicians who want to be rheumatologists like the idea of “being a doctor,” someone who enjoys the doctor–patient relationship in all its variety and likes to rely on old-fashioned skills of the history and physical exam. Even if the ultrasound machine beckons, especially those contraptions that produce whiz-bang multicolor Power Doppler images, I suspect that many—if not most—of the decisions rheumatologists will make now and in the future will result from inspection and palpation of joints. Furthermore, for patients who present with systemic complaints, percussion and auscultation will remain important parts of the diagnostic repertoire.

I have enormous respect for real diagnosticians. I still remember the time when, as a medical student, I watched with amazement as an attending on what was then called the Chest Service precisely delineated the boundaries of a lung abscess by thumping with his fingers and hearing an E-to-O change with this stethoscope. “Wow,” I said to myself, “that’s slick,” although it was a long time ago, and I might have said neat, groovy, or cool instead.

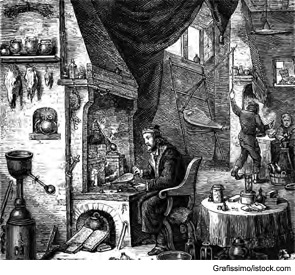

Perhaps unique among specialists, rheumatologists value clinical skill and acumen and continue to aspire to serve patients just the way Hippocrates, Galen, or Osler did in bygone eras. Our spirit resides in the confines of a little black bag, squeezed next to a tuning fork, reflex hammer, or tape measure. I suspect, however, that the only little black bags anyone carries around anymore on the ward are made by Prada. Kate Spade could probably do a nifty job, but I do not think that the medical profession would be ready for a profusion of colors called coral, sophronitis, or sunshine.

Although our applicant pool was great, I nevertheless cannot help but worry about the direction of our specialty since, among the people who indicated an interest in research, not one said that he or she wanted to do basic science. Rather, … aspiring trainees professed an interest in translational research.

Bringing Science to the Applicant Pool

Although our applicant pool was great, I nevertheless cannot help but worry about the direction of our specialty since, among the people who indicated an interest in research, not one said that he or she wanted to do basic science. Rather, among those interested in academics, the aspiring trainees professed an interest in translational research. I think I know what basic or clinical research is, but the concept of translational research still eludes and puzzles me. I have yet to get a clear vision of the scope of translational research and how to train someone for this endeavor.

In the usual realm of commerce and politics, translators are middlemen and go-betweens. The root of the word actually means to carry over. The skill of translators is the mastery of two languages and the facility to render in real time—in the flick of an eye and the snap of a finger—the sense of words in one language into another in a bidirectional whir of word wizardry.

The training of a translator is therefore seemingly straightforward. If you want to be a French/English translator, you learn English if you speak French and French if you speak English. I doubt that simply having the knowledge of two languages is sufficient to be a good translator. The process must involve elaborate brain reprogramming, since words that go into the head in one language must come out in another with a fundamentally different vocabulary and syntax.

So, if a prospective applicant comes to me saying that he or she wants to be a translational investigator (i.e., a translator), the first question I ask is the following: “How many languages do you speak?” If the answer is only one—clinical medicine—the obvious answer is to learn the other—science. A person cannot translate with only one language. Translation is never unitary. It is inevitably and ineluctably dyadic.

I can sympathize with the aspirations of the trainees for their academic careers, and I applaud their desire to perform relevant, patient-based research. Such research can amalgamate cutting-edge science with state-of-the-art clinical observations, elucidate the effects of a new therapy on physiology or immunology, or take an exciting new discovery on a journey from the bench to the bedside to become the next targeted therapy. The devil is in the details, however, and translational research is very difficult if you know only the clinical part and are a novice or uninitiated in the world of hard science. Bench scientists live in an ivory tower (or ivory cold room or ivory incubator or whatever). To engage them in collaboration, you need to speak their language. Learning that language—like learning German, Sanskrit, or Urdu—is no slam dunk. It takes time—and I mean years. There is no six-week Berlitz course to help you converse in biochemistry or cell biology.

Although the trainees we interviewed had remarkable life experience, working in rural clinics in Guatemala or teaching “health” to inner-city high school students, their encounters with the laboratory were in general quite transient. For some, it was a quick project during their undergraduate years that unfortunately, but not surprisingly, never came to fruition; a few hours each week is simply not enough time to make headway on a project that should be a full-time job. For the others, the lab experience was a bunch of hum-drum exercises from Chemistry or Biology 101. The trainees spoke as if the lab was a distant and foreign place, impenetrable to the ordinary intellect, governed by a special code harder to crack than the Rosetta Stone.

In Defense of Basic Research

Although basic research can be arduous and frustrating, especially now when the funding levels are in the single digits, its rituals can be learned, its heights can be scaled, and the rewards can be gained. Please remember that all of the major advances in the treatment of rheumatic disease started as basic laboratory research that was neither translational nor clinical in origin and mostly had nothing to do with rheumatology. After all, tumor necrosis factor (TNF) got its name from a factor that could kill tumor cells in mice; interestingly, the cytokine we know and love as TNF could equally well have been called cachectin. Cachectin is the same molecule as TNF, with this activity found by an inspired investigator trying to understand why animals infected with certain pathogens stopped eating and lost weight.

In their extraordinary work, the discoverers of TNF (or cachectin) were pursuing fundamental questions, and they did not have rheumatoid arthritis (RA) on their radar screens. In the chaos and jumble of scientific inquiry, however, investigators eventually saw a connection with RA, allowing anti-TNF (after a detour in sepsis) to find a place in clinic where today it is a mainstay in a treatment paradigm that is making remission increasingly possible. That, dear readers, is what scientific advance is all about. Without a long gestation period of heavy duty basic research—protein purification, sequencing, expression cloning, development of functional assays, shooting up mice—the role of TNF in the pathogenesis of inflammatory arthritis likely would have been missed. It was only later when a treasure chest of basic science observations had been filled to the brim that a translational conversation could begin. Most importantly, the individuals pursuing this initial work made progress because they could speak both clinical and basic research languages, making translation possible. Look at the early publications of these investigators. They are replete with top-flight basic science. Without the ability of these pioneers to zig and zag between the clinic and the lab, anti-TNF would likely have been shelved long ago.

Becoming Bilingual

Time was, students in the United States had to take a foreign language to graduate from high school or college. Belief was strong that a truly educated person should know two languages and, by implication, two cultures. (Did you think my adeptness with dropping bon mots and navigating the boîtes on the Left Bank came out of thin air? No, mes amis, it was four years of high school French, disciplined by teachers we called Monsieur and Madame who, sacré bleu, made us conjugate verbs incessantly—Je suis, tu es, il est—working us so hard my derrière turned into rien de tout, and then we had to read Le Malade Imaginaire, La Peste, and Le Père Goriot in French in paperback books whose pages I had to slit apart with a silver letter opener.)

To you trainees who want to do translational research, I want you to look deep into your souls and ask yourself a serious question: “Do I know two languages? Do I know science as well as medicine?” If the answer is no, then I say that you should come to the lab for a good long stay. Get a few feet of bench space and a computer with lots of memory. Learn what a mole is, how to make a buffer of pH 7.4, and how to take that flow cytometer for a spin. Make PubMed your friend, and start reading articles. Unlike journal club, no skipping the “Materials and Methods,” because this section often contains the key nuggets for translation.

In the world of modern research, it takes two to tango. Therefore, start practicing your dancing; whether it is dancing with the stars or dancing with the nerds, only time will tell.

Applicants for the class of 2012, as you rank your choices for fellowship, bonne chance. Along with many of my colleagues throughout academic rheumatology, I will welcome you to the realm of basic research at any time. I promise you will work hard and enjoy it, and I guarantee that you won’t have to wear a dark suit. In my lab, jeans will be just fine.

Au revoir, mes élevés. À bientôt.

Dr. Pisetsky is physician editor of The Rheumatologist and professor of medicine and immunology at Duke University Medical Center in Durham, N.C.