The pathologist who performed the autopsy was awestruck. In all his years of dissecting the bodies of the deceased in search of answers, he had never observed such a cause of death. His thick Glaswegian brogue was almost indecipherable to my Canadian ears, but the evidence that he held in his hands was irrefutable.

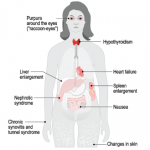

The normally flaccid bowel appeared rod-like rigid, looking and feeling more like a stovepipe, its walls studded with stercoral ulcers, those rarely seen perforations caused by chronic, massive fecal impaction explaining why Simone had been complaining so bitterly.1 Mon dieu! A picture is worth a thousand words. The pervasive infiltration of amyloid throughout her body had rendered her blood vessels pulseless and wrecked her kidneys, too.

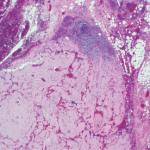

As we peered through microscopes to study these tissues, the striking apple green birefringence of the Congo red stain confirmed that their destruction had been caused by amyloid, the starch-like protein whose predilection to invade and damage selected tissues and organs is well known to rheumatologists.

Perhaps its penchant for linking to the glycosaminoglycans that form the backbone of connective tissue led to amyloid crossing the rheumatologist’s path periodically. Recall the well-described, though rarely seen, shoulder pad sign—a condition caused by the accumulation of massive sheets of amyloid material in the shoulder joints, giving the patient, usually a frail individual in their eighth decade of life or older, the appearance of a football player donning shoulder pads.2 There are also those rare occasions in which the ensuing synovial thickening of the knuckles that was characteristic of amyloid arthritis, misled clinicians into believing the patient had rheumatoid arthritis. These vignettes recall a bygone era when amyloidosis seemed more prevalent.

From the Body to the Brain

Although amyloidosis has faded from view, it has not entirely disappeared. There remain a few active centers of excellence for the study of amyloidosis, such as the one established at Boston University Medical Center, and sporadic cases of the disease affecting the heart, lung or peripheral nerves occasionally meet up with rheumatology consult services. For the most part though, the intense interest in the biology of amyloid has shifted from the body to the brain, where it continues to gain interest as a major target of study among neuroscientists.

For good reason, amyloidosis is often linked with the work of the noted German neuropathologist and clinician, Alois Alzheimer, MD, whose paper, “On a Peculiar Severe Disease Process of the Cerebral Cortex,” presented at a conference in 1906, described a curious finding: the presence of neurofibrillary tangles in the cerebral cortex of a patient, Auguste D.

Cognitively normal people can accumulate a large amyloid load in their brains, so the simple accumulation of amyloid in the brain is insufficient to cause dementia. However, there appears to be a much clearer correlation between the number of neurofibrillary tangles containing tau found post-mortem & the degree of dementia observed in life.

Auguste D. was described as a 51-year-old delusional, forgetful, disoriented, anxious, suspicious, unruly and disruptive woman who exhibited a striking personality change over the course of one year. She died of pneumonia, and Dr. Alzheimer made these prescient post-mortem observations of her brain cells: “In the center of an otherwise almost normal cell there stands out one or several fibrils due to their characteristic thickness and peculiar impregnability.” Regarding the senile plaques that he also observed, he wrote: “Numerous small miliary foci are found in the superior layers. They are determined by the storage of a peculiar material in the cortex.”3