esigner491 / shutterstock.com

Historically, the early approach for treating interstitial lung disease (ILD) due to systemic sclerosis (SSc) involved immunosuppressant therapy, primarily with cytotoxic agents.1 Glucocorticoids in combination with another immunosuppressant agent, such as oral azathioprine or cyclophosphamide, were often used to treat patients with severe, progressive SSc-ILD.2 However, direct evidence to support this therapeutic approach was lacking until the publication of Scleroderma Lung Study (SLS) I, a randomized, controlled trial comparing 12 months of oral cyclophosphamide with 12 months of placebo in 158 patients with relatively early SSc (<7 years from the onset of the first non-Raynaud’s symptom of SSc) and evidence of active alveolitis.3

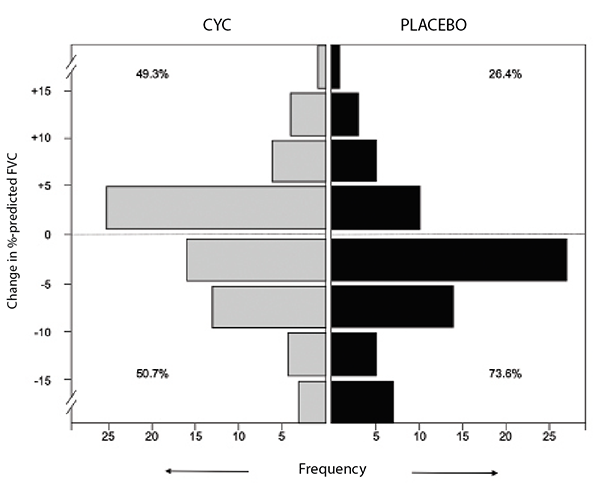

In SLS I, patients randomized to cyclophosphamide experienced a modest improvement at a group level in the primary endpoint of the forced vital capacity (FVC) percent-predicted compared with placebo (2.53%; P<0.03) (see Figure 1).3 Moreover, patients randomized to cyclophosphamide also experienced clinically meaningful improvements in quality of life, dyspnea measures and several secondary endpoints, including total lung capacity percentage predicted and the extent of both visually assessed and computer-assisted quantitative lung fibrosis.3,4

(click for larger image) Figure 1: Frequency distribution of changes from baseline to 12 months in FVC percent-predicted by treatment arm in SLS I.

However, the benefits of cyclophosphamide were tempered by safety concerns because more adverse events were observed in this study arm, including higher rates of leukopenia and neutropenia compared with placebo.3 Further, one year after treatment cessation, the FVC percent-predicted returned to baseline in both study arms. A responder analysis revealed a loss of any significant treatment effect of cyclophosphamide at 24 months for both the FVC percent-predicted and total lung capacity percent-predicted.5

Study #2

The findings of SLS I highlighted the need for additional studies to identify novel therapeutic agents for SSc-ILD with better safety profiles and more sustained treatment effects. SLS II was conceived to evaluate the safety and efficacy of daily mycophenolate mofetil, an agent that possesses both anti-fibrotic and immunomodulatory effects.6 This study compared 24 months of mycophenolate mofetil with 12 months of oral cyclophosphamide followed by 12 months of placebo in 142 patients with SSc-ILD. The entry criteria and investigating centers were nearly identical in SLS I and II.

The primary hypothesis of SLS II was that patients assigned to mycophenolate mofetil would experience significantly greater improvement in FVC percent-predicted compared with patients assigned to cyclophosphamide. This hypothesis was largely based on the assumption that continued treatment with mycophenolate mofetil for 24 months would lead to a sustained improvement in FVC percent-predicted, while cessation of cyclophosphamide at 12 months would lead to a decline in FVC percent-predicted back to baseline values at 24 months.

The final results of SLS II indicated no difference in the course of FVC percent-predicted over 24 months in patients assigned to mycophenolate mofetil vs. cyclophosphamide.6 Both treatment arms experienced significant and clinically meaningful improvements in their FVC percent-predicted over the course of the trial (see Figure 2). Sixty-five percent of those assigned to cyclophosphamide and 72% of those assigned to mycophenolate had stable or improving pulmonary function as measured by FVC percent-predicted. In addition, both treatments resulted in significant improvements in dyspnea (as measured by the transitional dyspnea index), cutaneous sclerosis and extent of radiographic fibrosis and ILD; however, no significant differences between treatment groups were observed in any of the outcome measures.