After 30 years of private practice in Hixson, Tenn., rheumatologist Joseph E. Huffstutter, MD, isn’t worried about squeezing in a new referral from a primary care colleague across the river in Chattanooga. Dr. Huffstutter and his four partners accommodate nonurgent referrals in about six weeks; patients with immediate needs are seen in a day or two.

But Dr. Huffstutter knows his practice is more the exception than the rule in Tennessee. Patients on the other side of the state, some 300 miles to the west in Memphis, are in far more desperate straits. “The wait time for a new patient in Memphis is six months,” says the past president of the Tennessee State Rheumatology Society. “We have more rheumatologists in Chattanooga, and Memphis is four times as big as we are.”

About 100 miles northeast in Knoxville, a city with nearly 200,000 residents and a major university, “there is a real dearth of rheumatologists,” Dr. Huffstutter says. And subspecialists are even scarcer as you travel farther north toward western Virginia. “There are several medium-size cities that just don’t have any coverage,” he says. “It’s six months or longer to get any rheumatology care.”

Patient access in rural and underserved U.S. communities is a serious issue—and not unique to rheumatology. Experts point to a multitude of reasons: an aging workforce, uncertain business climate and government regulation—to name a few.

“Access is a true, regional issue,” says Daniel Battafarano, DO, a retired U.S. Army colonel who is chief of the Rheumatology Division at San Antonio (Texas) Military Medical Center and a member of the ACR’s Committee on Rheumatology Training and Workforce Issues. “In the northeast United States, you might be a stone’s throw away from accessing a rheumatologist, but this is in dramatic contrast to Western states like Idaho or Nevada, which are underserved.”

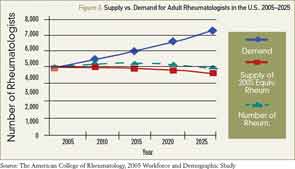

And access to subspecialists in underserved areas isn’t getting better anytime soon (see Figure 1).

“There is no doubt in my mind patient access is becoming more difficult,” Dr. Battafarano says. “It’s simple arithmetic. More than half of our rheumatologists are over age 50 and could retire in the next 10–15 years. At the same time, the population in America is expanding while we are implementing the Affordable Care Act, which generates its own access challenges.”

Source: The American College of Rheumatology, 2005 Workforce and Demographic Study

International State of Affairs

Up until the year 2000, a patient in the United Kingdom referred to a rheumatologist could wait six, nine, even 18 months for an initial visit, according to Simon Bowman, BSc, MBBS, PhD, FRCP, consultant and honorary professor of rheumatology at University Hospitals Birmingham NHS Foundation Trust. In 2000, however, the maximum waiting time target for outpatient appointments was set at 12 weeks.1

“That was a big change, in terms of patient access,” Dr. Bowman says. “Suddenly, the hospitals had to collect data and make sure patients were booked in the 12-week timeframe. It made a very big difference to outpatient specialties like rheumatology, dermatology, etc.”

Even with regulation, a recent report showed “unacceptable” wait times for rheumatoid arthritis and psoriatic arthritis patients in the U.K. The research showed a 10% increase in “unacceptable delays” of 12 weeks or more to see a specialist in the past 10 years.2

“It is true that in many areas the time (from referral to specialist visit) is slipping a little bit,” Dr. Bowman says. “But the data probably should be taken with caution. Things are much improved over the past 10–15 years. On the whole, there probably are regional variations. In my locality, rheumatologists are able to meet these ideals.”

Meeting the “window of opportunity” target is reliant on all cogs in the health system wheel functioning correctly, Dr. Bowman says. Nurses and support staff, positions that are first to be cut in times of economic downturn, are critical to follow-up care. Another key is continued education for patients and referring physicians.

“In this country, our focus is on new patients, instead of follow-up,” he says. “That can have an impact on subsequent care. That can be somewhat challenging, and it’s complex. In Europe, my colleagues are expected to see fewer patients than in the U.K., and are expected to spend more time with follow-up. Probably at the moment, there is not a great deal of prospect for that to be modified.”

The U.K. is dealing with similar obstacles to patient access in the U.S., in terms of an aging population, workforce capacity and government cuts to budgets, says Alan J. Silman, MD, medical director of Arthritis Research UK.

“The issue here is what part of the workload can be handled in primary care, particularly for non-inflammatory joint disease, including osteoarthritis, back pain and fibromyalgia,” says Dr. Silman, who notes new initiatives, such as the “best practice tariff” and “treat to target,” allow for patients with newly diagnosed inflammatory arthritis to be seen and started on treatment quickly. “There are a number of models being developed, with closer integration of primary and secondary care, including, for example, development of skilled physiotherapist and other healthcare professionals who can manage many of these patients.”

Source: The American College of Rheumatology, 2005 Workforce and Demographic Study

The Numbers

In 2005, the ACR published research that showed demand for rheumatologists in 2020 would be about 6,500, but only slightly more than 5,000 rheumatologists would be in active practice. By 2025, the gap was projected to widen to 2,000 (see Figure 2).

Howard Blumstein, MD, realizes the U.S. system is headed for “a real problem” and is concerned about the impact the Affordable Care Act will have on patient-access issues.

“The future here is extremely hazy,” says Dr. Blumstein, a partner in Rheumatology Associates of Long Island, N.Y. “I wonder how much the [U.K.] model will [translate] here, where we will become managers of armies of nurse practitioners or physician assistants doing the day-to-day work. Personally, that’s not why I went into this field. To me, that’s scary stuff.”

Changes in workforce demographics and productivity are generational, Dr. Blumstein says. He says it’s hard to argue with newly minted doctors choosing work-life balance or taking a secure salary in a hospital-employed position.

Dr. Huffstutter, whose daughter is in medical school, realizes that more women in medicine—about 60% of rheumatology trainees are women—will affect patient access in the future.

“This is a gender-shift issue in medicine,” Dr. Battafarano says. “It is conceivable that a subset of female physicians, for a variety of reasons, will practice part time at some point in their career. We may be graduating and training more rheumatologists in 2014 than we were in 2000, but the gender shift definitely will influence access to rheumatology care. This is not unique to rheumatology, but is true for other subspecialties as well.”

Short-Term Fix

No single solution will fix patient-access issues in the U.S., experts agree. Some say, “Train more rheumatologists.” Some say rheumatologists need to do a better job educating primary care and patients on the importance of early diagnosis and referral. Others, but not all, think that easing limitations on nurse practitioners (NPs) and physician assistants (PAs) is a good place to start. But everyone seems to agree that those are only pieces of the larger puzzle.

“In my opinion, the biggest short-term solution for rheumatology access is training more NPs and PAs,” Dr. Battafarano says. “That would require us to recruit them into the rheumatology profession, and it would require us to have more formal training programs—in addition to training some in private practice settings. Longer-term solutions to improve access include recruiting rheumatology providers to underserved areas and better training for [primary care physicians] to recognize and treat RA early.”

Richard Quinn is a freelance writer in New Jersey.

References

- Department of Health. The NHS Plan: A plan for investment, a plan for reform. London: Department of Health, 2000. July 1, 2000. http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20130107105354/http://www.dh.gov.uk/en/Publicationsandstatistics/Publications/PublicationsPolicyAndGuidance/DH_4002960.

- More rheumatoid arthritis and psoriatic arthritis patients waiting “unacceptable” times for referral than a decade ago. Business Wire website. Jan. 29, 2014. http://www.businesswire.com/news/home/20140129005500/en/Rheumatoid-Arthritis-Psoriatic-Arthritis-Patients-Waiting-%E2%80%9CUnacceptable%E2%80%9D#.U1A-ZBlRE5N.