Yevhen Vitte/shutterstock.com

SAN FRANCISCO—Lung involvement is a frequent and often life-threatening manifestation of the connective tissue diseases (CTDs) that are commonly encountered by rheumatologists. A variety of rheumatic diseases can affect the lungs, including systemic sclerosis, rheumatoid arthritis, vasculitis, lupus, polymyositis/dermatomyositis (PM/DM) and Sjögren’s syndrome. A panel presentation on lung disease associated with rheumatic diseases at the California Rheumatology Alliance 2016 Medical and Scientific Meeting in May highlighted the challenges of managing this difficult population and the need for rheumatologists to collaborate with pulmonologists and other specialists. Strategies to help with prompt or early diagnosis were emphasized. The initial presentation of lung disease in this patient population may be to either the rheumatologist or the pulmonologist.

The overlap of autoimmune and connective tissue diseases with interstitial lung disease (ILD)—which involves inflammation, scarring and thickening of the lung’s interstitium—represents a spectrum of conditions and severities, said Aryeh Fischer, MD, associate professor of medicine in the Divisions of Rheumatology and Pulmonary Sciences at the University of Colorado School of Medicine. Rates of ILD are estimated to be 45% or higher in systemic sclerosis, 20–30% in rheumatoid arthritis and 20–50% in PM/DM, with ILD a leading cause of death in these conditions.

“We have to work together on shared patients, because ILD is a common manifestation of CTD. Too often, the pulmonologist is not as familiar with the underlying autoimmune factors, and the rheumatologist may not be looking carefully enough for the presence of lung involvement,” Dr. Fischer said. “For the rheumatologist, it’s important to connect the dots and assess for an autoimmune basis for presumed idiopathic ILD.” These patients may have subtle autoimmune features, such as Raynaud’s disease, digital edema, inflammatory arthritis and the skin lesions of “mechanic hands.”

Further, in treating extra-thoracic disease manifestations, such as synovitis or myositis, “we need to be aware of what’s going on in the lungs because the presence of lung disease may impact choice of immunosuppressive therapy,” he said. “In assessing ILD in those with CTD, we don’t conclude that this is a CTD with ILD until we go through a process of elimination for the possible causes for symptoms. Ask what else could be the cause. Does the ILD pattern fit? What other organs are involved? Are there manifestations of other etiologies?”

‘We have to work together on shared patients, because ILD is a common manifestation of CTD. Too often, the pulmonologist is not as familiar with the underlying autoimmune factors, & the rheumatologist may not be looking carefully enough for the presence of lung involvement.’ —Dr. Aryeh Fischer

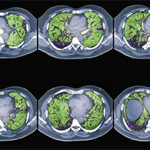

The high-resolution computed tomography (CT) scan is the diagnostic test of choice for assessing disease extent and severity in ILD, Dr. Fischer said. He encouraged rheumatologists to read the radiologist’s report about what the scan is showing in the lungs. “Then actually see the images for yourself. By looking at the actual scans, one can get a better sense of the degree of lung involvement and appreciation of its severity,” he urged. “Listen to our patients’ lungs. Ask about their functional limitations from a respiratory standpoint.” Assess the impact of dyspnea on activities of daily living. “We can be lulled into a false sense of security about their lung function because these patients may be sedentary from their rheumatic disease and, thus, aren’t reporting respiratory symptoms.”