Yevhen Vitte/shutterstock.com

SAN FRANCISCO—Lung involvement is a frequent and often life-threatening manifestation of the connective tissue diseases (CTDs) that are commonly encountered by rheumatologists. A variety of rheumatic diseases can affect the lungs, including systemic sclerosis, rheumatoid arthritis, vasculitis, lupus, polymyositis/dermatomyositis (PM/DM) and Sjögren’s syndrome. A panel presentation on lung disease associated with rheumatic diseases at the California Rheumatology Alliance 2016 Medical and Scientific Meeting in May highlighted the challenges of managing this difficult population and the need for rheumatologists to collaborate with pulmonologists and other specialists. Strategies to help with prompt or early diagnosis were emphasized. The initial presentation of lung disease in this patient population may be to either the rheumatologist or the pulmonologist.

The overlap of autoimmune and connective tissue diseases with interstitial lung disease (ILD)—which involves inflammation, scarring and thickening of the lung’s interstitium—represents a spectrum of conditions and severities, said Aryeh Fischer, MD, associate professor of medicine in the Divisions of Rheumatology and Pulmonary Sciences at the University of Colorado School of Medicine. Rates of ILD are estimated to be 45% or higher in systemic sclerosis, 20–30% in rheumatoid arthritis and 20–50% in PM/DM, with ILD a leading cause of death in these conditions.

“We have to work together on shared patients, because ILD is a common manifestation of CTD. Too often, the pulmonologist is not as familiar with the underlying autoimmune factors, and the rheumatologist may not be looking carefully enough for the presence of lung involvement,” Dr. Fischer said. “For the rheumatologist, it’s important to connect the dots and assess for an autoimmune basis for presumed idiopathic ILD.” These patients may have subtle autoimmune features, such as Raynaud’s disease, digital edema, inflammatory arthritis and the skin lesions of “mechanic hands.”

Further, in treating extra-thoracic disease manifestations, such as synovitis or myositis, “we need to be aware of what’s going on in the lungs because the presence of lung disease may impact choice of immunosuppressive therapy,” he said. “In assessing ILD in those with CTD, we don’t conclude that this is a CTD with ILD until we go through a process of elimination for the possible causes for symptoms. Ask what else could be the cause. Does the ILD pattern fit? What other organs are involved? Are there manifestations of other etiologies?”

‘We have to work together on shared patients, because ILD is a common manifestation of CTD. Too often, the pulmonologist is not as familiar with the underlying autoimmune factors, & the rheumatologist may not be looking carefully enough for the presence of lung involvement.’ —Dr. Aryeh Fischer

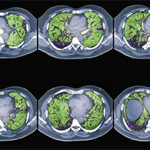

The high-resolution computed tomography (CT) scan is the diagnostic test of choice for assessing disease extent and severity in ILD, Dr. Fischer said. He encouraged rheumatologists to read the radiologist’s report about what the scan is showing in the lungs. “Then actually see the images for yourself. By looking at the actual scans, one can get a better sense of the degree of lung involvement and appreciation of its severity,” he urged. “Listen to our patients’ lungs. Ask about their functional limitations from a respiratory standpoint.” Assess the impact of dyspnea on activities of daily living. “We can be lulled into a false sense of security about their lung function because these patients may be sedentary from their rheumatic disease and, thus, aren’t reporting respiratory symptoms.”

Dr. Fischer recommended the pulmonologist’s “six-minute walk test” as a good way to assess functional status over time. It measures distance walked, heart rate, oxygen desaturation and how musculoskeletal disease affects performance, although it won’t distinguish ILD from pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) or other causes of hypoxia. He urged rheumatologists to keep their stethoscope handy and listen for crackles. But don’t assume that absence of crackles or of dyspnea means lack of ILD.

A Paucity of Data for Effective Treatment of Scleroderma

Although scleroderma patients with ILD typically face poor prospects, Francesco Boin, MD, director of the Scleroderma Center at the University of California, San Francisco, offered some additional perspectives on their management, treatment and future directions for research. “Scleroderma is a heterogeneous, multi-organ disease with overlapping features and burden of side effects,” he said. There are no proven, targeted therapies—no disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (DMARDs)—for scleroderma, and a paucity of evidence-based data exist for what is effective.

As a result, management strategies come to the fore—starting with encouragement for smoking cessation by the patient. Promotion of vaccinations is also important, because any infection in the lungs can trigger new disease. Other supportive care strategies include management of esophageal dysfunction, acid reflux and risk for aspiration; pneumocystis pneumonia prophylaxis when indicated; oxygen therapy to help minimize hypoxemia; patient education and support including referrals to peer groups; and palliative care for breathlessness, cough and depression.

“Educate the patients that this is a chronic disease for life,” Dr. Boin said. “Tell them that a group of professionals will be caring for them, but they also need to learn more about their disease.”

The challenge for rheumatologists is knowing who to treat and when to treat and distinguishing early vs. end-stage disease, he said. Not all patients are affected to the same degree, so it’s important to determine severity of disease.

“With a lot of these patients, where the course of their disease is relatively benign, we wonder: do we really need to treat?” Patients with the best chance of responding to treatment may be those with higher risk of declining lung function, predicted poor outcome or more extensive disease at presentation.

Dr. Boin also emphasized looking for changes in function and using pulmonary function tests to assess disease progression over time.

The efficacy of corticosteroids for CTD‑ILDs remains controversial because no randomized controlled trials have yet proved their efficacy at moderate to high doses. In scleroderma patients, there is also the potential risk of renal crisis and other side effects from corticosteroid treatment.

“In our scleroderma clinic, we are very cautious with steroids and try to minimize their use to only when really necessary.” Other treatment options currently used for CTD-ILD include non-selective immunosuppressive therapies such as cyclophosphamide and mycophenolate mofetil. A recently published, randomized trial, the Scleroderma Lung Study-II, comparing mycophenolate and cyclophosphamide, shows possible effectiveness for both drugs.1 Findings suggest that mycophenolate is associated with fewer side effects and may have a safer profile, Dr. Boin said.

High-dose cyclophosphamide therapy with bone marrow rescue by hematopoietic stem cell transplantation has been shown to be feasible in scleroderma patients, with improvement of skin disease and stabilization of lung function. But high treatment-related mortality remains a relevant limitation to this approach. Novel treatments with anti-fibrotic properties, recently approved by the Food and Drug Administration for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, include pirfenidone and nintedadib.2,3 Future treatment options for scleroderma/CTD and ILD may include rituximab, tocilizumab and other biologic therapies, alone or in combination. Rituximab, a monoclonal antibody directed against B cells, is gaining popularity as several reports and case series have shown some benefit.

“Combination therapy using, at different stages of the disease, immunomodulators and anti-fibrotic drugs may be the most effective strategy, but it clearly awaits formal clinical studies to be further explored,” he said.

Pulmonary Hypertension Is Associated with Poor Prognosis

Dr. Fischer also discussed the diagnosis of pulmonary hypertension (PH), defined as elevated pulmonary blood pressure where the disease process causes thickening and constriction in the pulmonary artery. PH, which the World Health Organization has described in a clinical classification system of five patterns based on etiology,4 is characterized by increased pulmonary vascular resistance that causes the right-sided heart muscle to weaken and eventually fail.

One of these five types of PH is PAH, a condition of the pulmonary artery itself, with restricted flow and elevated rates of pulmonary artery pressure and pulmonary vascular resistance. In the REVEAL Registry, CTDs are associated with one-quarter of all PAH cases, while 10–15% of all systemic sclerosis patients develop PAH.5 PAH is also associated with other CTDs, including systemic lupus erythematosus, antiphospholipid syndrome and mixed connective tissue disease.

Effective screening should lead to earlier detection of PAH and earlier intervention with specific PAH therapies, Dr. Fischer said. Screening for PAH is very important, and it is indicated annually for all patients with systemic sclerosis and mixed connective tissue disease. There are different screening algorithms; none is perfect. But it is important to have a strategy for screening in place with a goal for earlier detection of disease, he emphasized. “You cannot confirm PAH without a right heart catheterization.” Consider a right heart catheterization if PAH is suspected, in order to confirm its presence, determine cardiac hemodynamics to help grade severity, guide therapy and exclude other etiologies for PH.

Van Selby, MD, assistant professor of medicine in cardiology at UCSF who works frequently with rheumatologists for patients who have PH, offered additional perspectives on PH and PAH during the lung disease panel at CRA. “Sometimes we use these two terms interchangeably, but it’s important to know which is which. Get familiar with the WHO classification of PH,” he urged attendees. Patients with PH should be referred to someone who has experience treating the condition, whether pulmonologist or cardiologist, Dr. Selby said. Some cardiologists may not be comfortable with it, “but we work closely with rheumatologists all the time for co-management of PAH in systemic sclerosis and other kinds of connective tissue diseases.”

Supportive therapy is also critical for these patients, including exercise. “Have patients start out easy and watch closely for chest pain, dizziness or fatigue. Cardiac or pulmonary rehabilitation programs where they are closely monitored are also helpful.” Other supportive measures include diuretics, digoxin, supplemental oxygen, oral anticoagulants and iron supplementation.

In terms of treatment for CTD-related PAH, an upfront two-drug strategy demonstrated superiority in the huge AMBITION trial comparing initial combination versus monotherapy with tadalafil and ambrisentan, Dr. Selby said.6 “That was a game changer for me and for the pulmonary hypertension community. People are now even studying initial therapy with more than two drugs. The idea is to hit it hard, as early as possible.” This includes treatment of PAH associated with systemic sclerosis, which can be hard to treat. “The last decade has seen many new medications approved for the treatment of PAH. The guidelines are still trying to find the optimal initial approach for each patient.”

Ultimately, once lung function drops below a certain level, lung transplant may be the only long-term treatment option for some of these patients. The speakers encouraged early referral to a transplant center to get patients assessed and enrolled on the transplant list before their condition is too far advanced.

Larry Beresford is an Oakland, Calif.-based freelance medical journalist.

References

- Tashkin DP, Roth MD, Clements PJ, et al. Mycophenolate mofetil versus oral cyclophosphamide in scleroderma-related interstitial lung disease (SLS II): A randomised controlled, double-blind, parallel group trial. Lancet Respir Med. 2016 Jul 25. pii: S2213–S2600(16)30152–30157. Epub ahead of print.

- King TE, Brandford WZ, Castro-Bernardini S, et al. A phase 3 trial of pirfenidone in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. N Engl J Med. 2014 May 29;370(22):2083–2092.

- Richeldi L, duBois RM, Raghu G, et al. Efficacy and safety of nintedanib in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. N Engl J Med. 2014 May 29;370(22):2071–2082.

- Simonneau G, Robbins I, Beghetti M, et al. Updated clinical classification of pulmonary hypertension. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009 Jun 30;54(1 Suppl):S43–S54.

- Badesch DB, Raskob GE, Elliott CG, et al. Pulmonary arterial hypertension: Baseline characteristics from the REVEAL Registry. Chest. 2010 Feb;137(2):376–387.

- Galie N, Barbera JA, Adaani EF, et al. Initial use of ambrisentan plus tadalafil in pulmonary arterial hypertension. N Engl J Med. 2015 Aug 27;373(9):834–844.