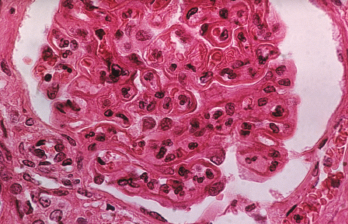

The pattern of lupus glomerular involvement is similar to that in membranous nephropathy, forming wire-loop lesions.

Biophoto Associates / Science Source

The incidence of lupus nephritis in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) has decreased over the past 50 years, according to a study from Gabriella Moroni, who works in the Nephrology Unit at Fondazione IRCCS Ca’ Granda Ospedale Maggiore Policlinico in Milano, Italy.1 Typically, renal involvement is part of the disease course for two-thirds of patients, the study authors reported. Renal involvement is a strong predictor of death and end-stage renal disease, but in their cohort, patient and renal survival markedly improved over time.

The authors wanted to examine changes in demographic, clinical and histological features of lupus nephritis, and changes in prognosis. Their retrospective study included 499 patients with lupus nephritis diagnosed between 1970–2016. The inclusion criteria included an SLE diagnosis based on ACR criteria, and biopsy-proven lupus nephritis. The patients were seen at one of four Italian referral centers.

The study’s 46-year follow-up was divided into three time periods of 15 years each: P1=1970–1985, P2=1986–2001 and P3=2002–2016, paralleling major advancements in lupus nephritis treatment.

About 85% of the study patients were women, and almost all were Caucasian; patients were followed for a median of 10.6 years. The number of male patients increased over time, from 6.6% in P1 to 12% in P2 and 19.6% in P3. The researchers noted an increasingly longer lag time between SLE and lupus nephritis diagnosis from 1970–2016 (P<0.0001). Age of lupus nephritis occurrence rose from 28.4 years in P1 to 29 years in P2 and 34.4 in P3 (P<0.001).

Researchers observed a progressive decrease in mean serum creatinine at diagnosis over time (1.8 mg/dL in P1, 1.2 mg/dL in P2 and 1.0 mg/dL in P3), as well as a significant decrease in the frequency of acute nephritic syndrome and rapidly progressive renal insufficiency. Significant growth was found in the prevalence of isolated urinary abnormalities from P1–P3.

Treatment & Outcomes

Among all time periods, more than two-thirds of patients were treated with methylprednisolone pulses as induction therapy. In P1, 29% of patients received induction therapy with corticosteroids alone, compared with 17.9% in P2 and 5.4% in P3. Immunosuppressive drug use grew more common over time, and they were added for maintenance therapy in 30.5%, 65.5% and 89.1% of patients in P1, P2 and P3, respectively. Cyclophosphamide was used by 50% or more of patients in each time period, and there was a decrease in the use of azathioprine as induction therapy from P1–P3; this was counterbalanced by an increase in the use of mycophenolate mofetil.

“Notably, the proportion of patients treated with [immunosuppressive drug] induction therapies progressively decreased over time,” the study says.

Among the 478 patients with outcomes available, 49.6% had complete renal remission in P1, compared with 48.4% in P2 and 58.5% in P3. The incidence of chronic kidney disease and end-stage renal disease lowered over time—it was 7.9% and 24.8% respectively, in P1; 8.5% and 9.1% in P2; and 4.5% and 1.3% in P3 (P<0.0001 for all comparisons). In P1, 20 patients died, compared with nine patients in P2 and eight patients in P3.

The chronic kidney disease-free survival rate at 10 and 20 years was 75% and 66% in P1, respectively; 85.5% and 80.2% in P2; and 91.5% in P3. The end-stage renal disease-free survival at 10 and 20 years was 87% and 80% in P1, respectively; 94% and 90% in P2; and 99% in P3.

Factors independently associated with poor renal outcomes included baseline serum creatine, high activity and chronicity index, arterial hypertension and the absence of maintenance immunosuppressive therapy. “In addition, male gender, older age and high serum creatinine were predictors of death,” the study says. The reason for a larger proportion of male patients over time was not clear to the authors, and they believe this finding should be confirmed in large multicenter studies.

Study limitations include its retrospective nature, no information on patients who achieved remission after induction therapy and the homogenous nature of the study population. However, the authors believe this is the first study that evaluates changes in demographic, clinical and histological features at the time of lupus nephritis presentation.

Discussion

The study results pleasantly surprised clinicians who regularly treat patients with SLE.

“These data suggest that advances in therapy have had a significant impact on major morbidities in SLE, which is remarkable and reassuring,” says Anca D. Askanase, MD, MPH, director and founder of the Columbia University Lupus Center and associate professor of medicine in the Division of Rheumatology at Columbia University Irving Medical Center in New York City, as well as a member of the Lupus Foundation of America’s Medical and Scientific Advisory Council.

“There are several very provocative findings from the study,” says Brad H. Rovin, MD, FACP, FASN, professor of medicine and pathology, the Lee A. Hebert Distinguished Professor of Nephrology and the director of the Division of Nephrology and vice chairman of medicine for research at Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center in Columbus, Ohio. “First, the duration of SLE before the diagnosis has increased significantly over the three time periods, with the longest difference in the modern era. Concomitant with this, the severity of [lupus nephritis] at presentation, based on serum creatinine, rapid renal deterioration and chronicity on biopsy, has declined in the current era.”

This may suggest that SLE is being diagnosed earlier, Dr. Rovin says. In turn, patients receive appropriate treatments, so lupus nephritis is less severe than in the past when it does develop.

Dr. Rovin, who is also a member of the Lupus Foundation of America’s Medical and Scientific Advisory Council, believes the finding of hypertension as a risk factor and the absolute levels of chronic kidney disease in the lupus nephritis population over time were two other important findings.

“One take-home lesson is the importance of meticulous blood pressure control in patients with lupus who develop lupus nephritis,” Dr. Rovin says. “This is a modifiable risk factor for poor kidney outcomes that can be readily addressed by the patient’s caregivers.”

“There also should be a lower threshold to perform renal biopsies [because] this can lead to improved renal outcomes,” says Jane E. Salmon, MD, who is the Collette Kean Research Professor at the Hospital for Special Surgery in New York City.

“Another take-home message is that better and more consistent use of immunosuppressive therapy seems to decrease end-stage renal disease,” Dr. Salmon says.

When reflecting on applicability of the study results to her own patient mix, Dr. Salmon sees some parallels. “At Hospital for Special Surgery, we have always been concerned when we see hypertension, increased creatinine and lack of consistent baseline immunosuppression in lupus nephritis patients. Further confirmation that these features are associated with a worse prognosis for renal disease underscores our need to continue to aggressively monitor and treat them,” she says.

Dr. Askanase points out differences in patient populations. “The population of patients at Columbia University Medical Center is predominantly Hispanic and black, of lower socioeconomic status, with complicated insurance and medical coverage issues, making it difficult to generalize some of these findings to our cohort and the U.S. patient population.”

Additionally, data from the U.S. Renal Data System, a national population-based registry of all people with end-stage renal disease on dialysis, show that incidence rates of end-stage renal disease due to lupus nephritis seem to be stable over time (1996–2004) despite therapeutic advances, Dr. Askanase says.2

Vanessa Caceres is a medical writer in Bradenton, Fla.

References

- Moroni G, Vercelloni PG, Quaglini S, et al. Changing patterns in clinical-histological presentation and renal outcome over the last five decades in a cohort of 499 patients with lupus nephritis. Ann Rheum Disease. 2018 Sep;77(9);1318–1325.

- Ward MM. Changes in the incidence of endstage renal disease due to lupus nephritis in the United States, 1996–2004. J Rheumatol. 2009 Jan;36(1):63–67.