Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is a heterogeneous, autoimmune, inflammatory, connective tissue disease affecting multiple organs. Neither central nervous system nor peripheral nervous systems are spared. The neurologic system is involved in a wide range of 10–80% of patients with SLE.

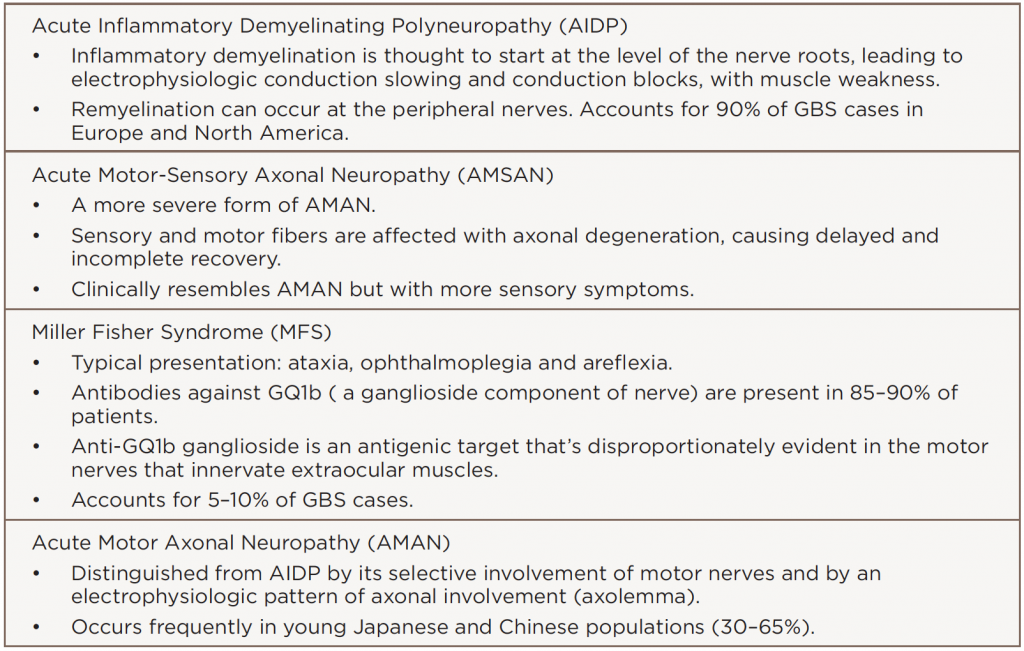

Peripheral neuropathy, such as Guillain-Barré syndrome (GBS) and its variants, can occur in neurologic complications of SLE. GBS variants include: 1) acute inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy (AIDP); 2) acute motor-sensory axonal neuropathy (AMSAN); 3) Miller Fisher syndrome (MFS), a rare variant with ocular involvement; and 4) acute motor axonal neuropathy (AMAN). Other rare variants can also occur.

Below, we present a case of an African-American woman with SLE presenting with the MFS variant of GBS. She completely recovered from MFS, which involved ophthalmoplegia, hyporeflexia and ataxia, with plasma exchanges and high-dose steroids. We also review the pathophysiology, treatment modalities and prognosis of this condition.

The Case

Top left: Ptosis of the left eye at presentation. Bottom left: Resolution of the ptosis after treatment. Top right: Left lateral rectus palsy at presentation. Middle right: Resolution of the left lateral rectus palsy, lateral gaze. Bottom right: Outward and upward gaze.

In early 2017, our rheumatology service was consulted for a 40-year-old African-American woman with complaints of double vision, bilateral lower-extremity numbness and ascending weakness with worsening over a two-month period. She was unable to walk without assistance on admission. A review of systems was positive for numbness in her lower legs ascending to her mid-chest, double vision, drooping of her left eyelid, one episode of diarrhea and difficulty walking.

Her medical history was also significant for hypertension. There was no history of intravenous drug use, tobacco use, HIV, hepatitis, clotting disorders or miscarriages.

She had a history of SLE with its onset in 2014, when it manifested with alopecia, mucosal ulcers, arthritis, elevated anti-nuclear antibodies (ANA), anti-double stranded DNA (anti-dsDNA), hypocomplementemia and anti-Smith (Sm) antibodies. She was placed on hydroxychloroquine 200 mg twice daily at that time.

The physical examination revealed a wide-based ataxic gait, a convergent gaze, left ptosis, left lateral rectus palsy (see Figure 1), horizontal diplopia, hyperpigmented lesions involving the antihielix/acoustic meatus, alopecia, hyporeflexia 0/5 in the ankles and knees bilaterally, 3/5 motor function for the left lower extremity and 4/5 for the right lower extremity. Her lower extremities had normal vibratory sensation below the level of the ankles. There was no clinical evidence of synovitis.

Miller Fisher syndrome (with its triad of ophthalmoplegia, ataxia & areflexia) is a rare variant of Guillain-Barré syndrome.

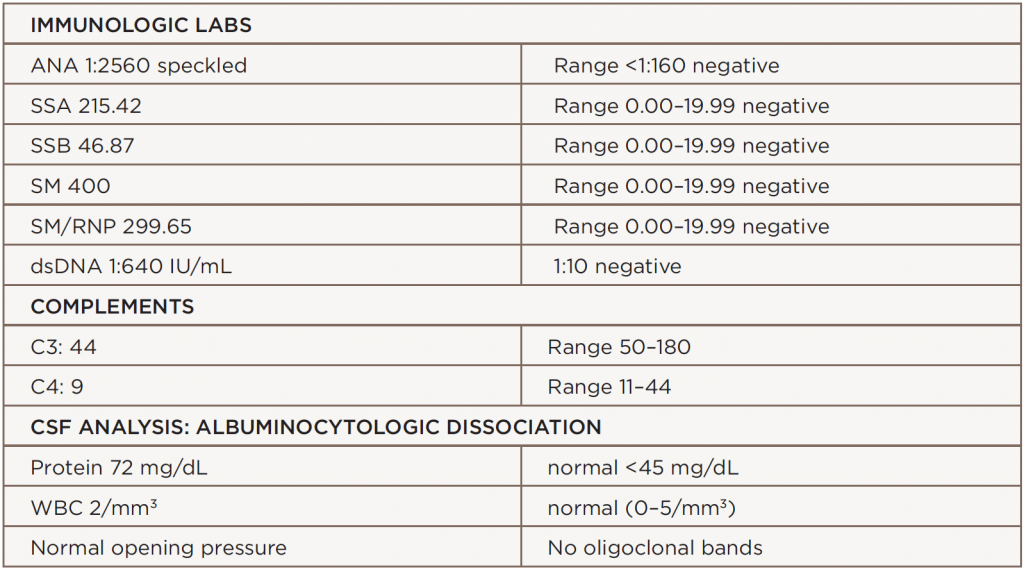

Laboratory analysis revealed an elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) of 127 mm/h, a C-reactive protein (CRP) level of 0.1 mg/L, hemoglobin of 10.9 mg/dL, hematocrit at 32.1%, hypocomplementemia (i.e., C3 at 44 and C4 at 9), ANA at 1:2560, anti-SSA antibody at 215, dsDNA at 1:640 and anti-Sm antibodies at 400. Creatinine phosphokinase (CPK), hepatitis panel, thyroid function tests, B12 and methylmalonic acid (MMA) were normal. Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) protein was elevated at 72 mg/dL, with a normal white blood cell count of 2 mm3. There were no oligoclonal bands. The angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE), neuromyelitis optica (NMO) immunoglobulin G (IgG) antibody, paraneoplastic panel, lyme cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and ganglioside GQ1b antibodies were negative.

Additional workup with magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of her brain revealed multiple, scattered, hyperintense foci throughout the deep white matter of the bilateral cerebral hemispheres of non-specific origin without an active demyelinating process. A magnetic resonance angiogram of her brain was negative for stenosis or occlusion. Cervical, thoracic and lumbar spine MRI revealed mild spondylosis without evidence of abnormal cord signal or enhancement.

The patient was pulsed initially with high-dose methylprednisolone for presumed active SLE. After the CSF revealed an albuminocytologic dissociation, we made a diagnosis of Guillain-Barré syndrome. The clinical picture of ophthalmoplegia, ataxia and areflexia clinched further diagnosis of MFS variant of GBS.

Based on these findings, we initiated plasma exchange for five days. Steroids were gradually tapered over three days, and she was eventually continued on a low, maintenance dose. She remained stable and did not develop GBS progression, such as respiratory failure. Her diplopia, lateral gaze palsy and ptosis resolved over the course of one week. Her muscle strength measured 5/5 in all extremities. Her gait was normal at the time of discharge.

Discussion

SLE is an inflammatory disease without an identified cause that can target every organ system. Its protean features allow for dramatic disease variation among patients. It is characterized by immunologic abnormalities that affect women of child-bearing age.

Patients with SLE may develop a wide array of neurologic features. GBS has appeared in a small number of SLE case reports. Patients with its acute form typically present with an ascending areflexic motor weakness without sensory loss. Others can present with a combination of sensory and/or motor findings (see Table 1). The MFS variant classically presents with the triad of ophthalmoplegia, ataxia and areflexia.

MFS is a rare GBS variant with ocular involvement. This subset is estimated to encompass 5–10% of GBS cases, with an incidence of one in 1 million. One-quarter of patients with MFS will develop extremity weakness in some form, which is the connecting factor to GBS. There may be incomplete presentations of MFS that present with different combinations, such as acute ophthalmoplegia without ataxia, or acute ataxic neuropathy without ophthalmoplegia. In addition, it is possible to see bulbar and facial weakness as presenting symptoms. Ophthalmoplegia in MFS is possibly the result of highly dense concentrations of GQ1b gangliosides, which are found in abducens, trochlear and oculomotor nerves. This imbalance of ganglioside antigenic targets results in anti-GQ1b antibodies binding to these ocular nerves causing damage leading to aberrant muscle function.6 anti-GQ1b antibodies appear in 85–90% of patients with MFS and may be a confirmatory finding.

The etiology of GBS in SLE patients is complex and poorly understood, but it likely involves different immunological mechanisms. It’s not clear whether GBS unmasks an underlying autoimmune disorder such as SLE, or if a lupus flare triggers GBS. In our patient, it seems a lupus flare triggered her GBS manifestation. It’s possible both may occur concurrently—her episode occurred during the winter months, when viral syndromes are common. GBS is an immune mediated condition and cellular and humoral mechanisms are involved.1

The three main pathophysiological mechanisms include the following.1

- GBS and SLE have a common trigger through molecular mimicry, which causes cross-reactivity because many GBS cases develop after infection. Campylobacter jejuni, Cytomegalovirus, Epstein-Barr virus, Zoster virus, Haemophilus influenza are known viral culprits. Vaccines have been indicated as well.6 Through this same mechanism, an immune response against neurons may contribute to SLE-induced neuropathy.

- A polyneuropathy may develop after a widespread immunological response in SLE that may cause autoantibody formation against gangliosides, such as GQ1b.

- A vascular complication of SLE, including microangiopathy, premature atherosclerosis, vasculitis and anti-phospholipid antibodies, can lead to ischemic demyelination, which may trigger a GBS-like response.

Despite similarities and differences, SLE and GBS present therapeutic challenges. Important: Treatment will differ when managing an SLE patient with GBS.

Although high-dose corticosteroid use is commonplace in SLE flares, it is not a typical first-line therapy for GBS. The main modalities of GBS therapy include plasma exchange (PLEX) and/or the administration of intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG). These treatments hasten GBS recovery, as shown in randomized controlled trials.2

Patients recover sooner when treated early. The beneficial effects of plasma exchange and IVIG are believed to be equivalent, although combination of these treatments is not beneficial.3

Studies have shown glucocorticoids are not beneficial in GBS alone and do not alter the outcome of GBS, but could possibly help neuropathies. In a systematic review and meta-analysis of six trials with 587 participants, glucocorticoid-treated patients with GBS showed no significant difference in disability grade compared with patients not treated with glucocorticoids.4

In an updated 2012 meta-analysis of six randomized controlled trials and 649 patients with GBS, treatment with plasma exchange was superior to supportive care.5 When comparing IVIG with plasma exchange for GBS treatment, the study found IVIG was as effective as plasma exchange.4 In our patient, plasma exchange was chosen for therapy.

Summary

Multiple central and peripheral neurologic complications can occur in SLE. We have highlighted the rare neurologic manifestations of SLE associated with GBS. This process is largely thought to be stimulated by an immunological process such as molecular mimicry.

GBS has many variants (see Table 2). Although rare, Miller Fisher syndrome typically presents with ophthalmoplegia, ataxia and areflexia. GBS may also present as new- and acute-onset SLE.

Prompt recognition of MFS (as well as other GBS variants) is urgent given treatment challenges. Overall, the prognosis is good with early diagnosis of SLE and GBS. No set standard for treatment exists, so therapies are usually guided by disease severity.

Our patient responded well, with complete resolution of her neurological symptoms following plasma exchange and steroid administration. This patient had discoid lupus, positive anti-dsDNA and low complements, but after her GBS resolved, she developed proteinuria of 8 grams and underwent a renal biopsy. Her biopsy confirmed membranous glomerulonephritis, which was treated with mycophenolate mofetil 1,500 mg twice daily, along with prednisone and hydroxychloroquine 200 mg twice daily. She responded to this therapy with a decrease in proteinuria.

Bottom line: Be very diligent in SLE patients when they have persistently positive serologies. Our patient had MFS as unusual neurologic and renal complications of SLE. Both were successfully treated, and she is doing well at present.

Sedrick Bradley, MD, is a rheumatology fellow at Ochsner Medical Center, New Orleans. He completed his residency at the University of Mississippi Medical Center, Jackson, Miss. His clinical and research interests include systemic lupus erythematosus and the role of T cell homeostasis in rheumatoid arthritis.

Nirupa J. Patel, MD, is a clinical associate professor of medicine in the Section of Rheumatology at LSU Health Sciences Center, New Orleans. Her special interests include HIV infection and myositis.

References

- Willison HJ, Jacobs BC, van Doorn PA, et al. Guillain-Barré syndrome. Lancet. 2016 Aug 13;10045(388):717–727.

- Hughes RA, Wijdicks, EF, Barohn R, et al. Practice parameter: Immunotherapy for GBS. Neurology. 2003 Sep 23;61(6):736–740.

- Patwa HS, Chaudhry V, Katzberg H, et al. Evidence-based guideline: Intravenous immunoglobulin in the treatment of neuromuscular disorders: Report of the Therapeutics and Technology Assessment Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2012 Mar 27; 78(13):1009–1015.

- Hughes RA, Swan AV, van Doorn PA. Intravenous immunoglobulin for Guillain- Barré syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012 Jul 11;(7):CD002063.

- Raphael JC, Chevret S, Hughes RA, et al. Plasma exchange for Guillain-Barré syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012 Jul 11;(7):CD001798.

- Chiba A, Kusunoki S, Obata H, et al. Serum anti-GQ1b IgG antibody is associated with ophthalmoplegia in Miller Fisher syndrome and Guillain-Barré syndrome: Clinical and immunohistochemical studies. Neurology. 1993 Oct;43(10):1911–1917.