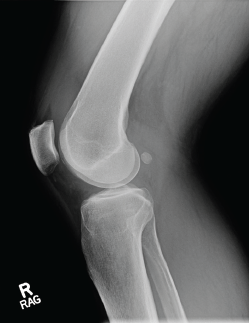

A 52-year-old man living in greater Boston with a history of hypertension presented at our rheumatology clinic with bilateral knee pain and swelling. He had been in his usual state of health until four months earlier when he developed right knee pain and swelling without an incipient trauma, which did not improve with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). His primary care physician ordered imaging: X-rays showed a moderate effusion, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed meniscal tears and a Baker’s cyst (see photos 1 and 2). He was referred to an orthopedist, but his symptoms spontaneously resolved.

One month ago, his left knee became swollen and painful.

The patient did not recall any flu-like illness, bull’s-eye rash or specific tick exposure. He had traveled to Cape Cod in the summer of the previous year and done some hiking there.

His primary care physician ordered Lyme antibody testing. Both the ELISA (enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay) and Western blot with 9 IgG bands and 2 IgM bands were strongly positive for Lyme disease.

Photo 1: An X-ray of the right knee reveals a moderate-sized effusion.

The patient was treated with a one-month course of 100 mg of doxycycline by mouth twice daily. However, he did not significantly improve and was referred to our rheumatology clinic. At his initial rheumatology visit, he complained of persistent bilateral knee discomfort and stiffness. He was unable to bike or walk for exercise.

On examination, we found he had a moderate right knee effusion with a suprapatellar component, mild warmth, and pain on extension and flexion. He also had a significant, left popliteal fullness with a smaller suprapatellar effusion and warmth.

Aspiration of the right knee was inflammatory with 22,180 white blood cells, 65% neutrophils. Crystal analysis, gram stain and culture tests were all negative. Laboratory studies showed systemic inflammation with an erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) of 38 mm/hr and a C-reactive protein (CRP) level of 36.4 mg/L.

Discussion

Lyme disease, a tick-borne infection with the spirochete Borrelia burgdorferi, is epidemic in areas of the U.S., particularly on the East Coast and in the upper Midwest, and is spreading into new geographic areas.1 Lyme disease occurs in phases, starting with the erythema migrans skin lesion. With dissemination, cardiac, neurologic and arthritic manifestations may develop. Musculoskeletal symptoms are present in all phases of Lyme disease, with arthralgias and myalgias often accompanying erythema migrans.

Frank arthritis is a late disease manifestation, developing in approximately 60% of untreated patients, a mean of six months and up to two years following erythema migrans.2 Lyme arthritis is the most common late manifestation of Lyme disease in the U.S. and accounts for one-third of the cases reported to the Centers for Disease Control & Prevention (CDC).1 Given the rising burden of Lyme disease, it is likely that Lyme arthritis will be an ongoing concern for physicians, particularly rheumatologists and orthopedists.

Lyme arthritis is an oligoarthritis most commonly affecting the knees. Other joints, such as the ankle, shoulder, elbow or wrist, may be involved. The arthritis may be migratory or intermittent, particularly initially, as well as persistent. Lyme arthritis is almost never a symmetric polyarthritis involving small joints.