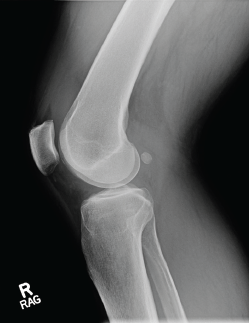

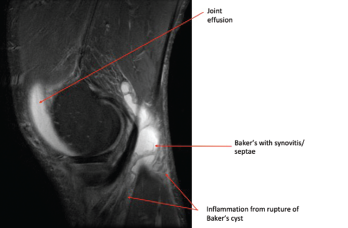

A 52-year-old man living in greater Boston with a history of hypertension presented at our rheumatology clinic with bilateral knee pain and swelling. He had been in his usual state of health until four months earlier when he developed right knee pain and swelling without an incipient trauma, which did not improve with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). His primary care physician ordered imaging: X-rays showed a moderate effusion, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed meniscal tears and a Baker’s cyst (see photos 1 and 2). He was referred to an orthopedist, but his symptoms spontaneously resolved.

One month ago, his left knee became swollen and painful.

The patient did not recall any flu-like illness, bull’s-eye rash or specific tick exposure. He had traveled to Cape Cod in the summer of the previous year and done some hiking there.

His primary care physician ordered Lyme antibody testing. Both the ELISA (enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay) and Western blot with 9 IgG bands and 2 IgM bands were strongly positive for Lyme disease.

Photo 1: An X-ray of the right knee reveals a moderate-sized effusion.

The patient was treated with a one-month course of 100 mg of doxycycline by mouth twice daily. However, he did not significantly improve and was referred to our rheumatology clinic. At his initial rheumatology visit, he complained of persistent bilateral knee discomfort and stiffness. He was unable to bike or walk for exercise.

On examination, we found he had a moderate right knee effusion with a suprapatellar component, mild warmth, and pain on extension and flexion. He also had a significant, left popliteal fullness with a smaller suprapatellar effusion and warmth.

Aspiration of the right knee was inflammatory with 22,180 white blood cells, 65% neutrophils. Crystal analysis, gram stain and culture tests were all negative. Laboratory studies showed systemic inflammation with an erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) of 38 mm/hr and a C-reactive protein (CRP) level of 36.4 mg/L.

Discussion

Lyme disease, a tick-borne infection with the spirochete Borrelia burgdorferi, is epidemic in areas of the U.S., particularly on the East Coast and in the upper Midwest, and is spreading into new geographic areas.1 Lyme disease occurs in phases, starting with the erythema migrans skin lesion. With dissemination, cardiac, neurologic and arthritic manifestations may develop. Musculoskeletal symptoms are present in all phases of Lyme disease, with arthralgias and myalgias often accompanying erythema migrans.

Frank arthritis is a late disease manifestation, developing in approximately 60% of untreated patients, a mean of six months and up to two years following erythema migrans.2 Lyme arthritis is the most common late manifestation of Lyme disease in the U.S. and accounts for one-third of the cases reported to the Centers for Disease Control & Prevention (CDC).1 Given the rising burden of Lyme disease, it is likely that Lyme arthritis will be an ongoing concern for physicians, particularly rheumatologists and orthopedists.

Lyme arthritis is an oligoarthritis most commonly affecting the knees. Other joints, such as the ankle, shoulder, elbow or wrist, may be involved. The arthritis may be migratory or intermittent, particularly initially, as well as persistent. Lyme arthritis is almost never a symmetric polyarthritis involving small joints.

Photo 2: This MRI of the right knee shows a large joint effusion and a ruptured Baker’s cyst with synovitis.

In patients with Lyme arthritis today, synovitis is usually the presenting manifestation of Lyme disease, and a history of suspicious tick bite or classic erythema migrans skin lesion is often lacking. Patients with Lyme arthritis rarely have a history of prior treatment for Lyme disease, because early treatment largely prevents the progression of infection to clinical arthritis. Unlike patients with early Lyme disease, who typically present in the late spring and summer, Lyme arthritis patients may present at any time of the year.

Patients of any age may develop Lyme arthritis, but children are particularly affected, with 35% of cases occurring in 10- to 14-year-olds, and older adults are also increasingly affected.1 Children may have more acute presentations. Adult Lyme arthritis patients generally don’t have the severity of pain that occurs in patients with septic arthritis caused by such bacterial organisms as Staphylococcus aureus.

Affected joints in Lyme arthritis often have large effusions (see photo 3). Baker’s cysts are commonly found. Rupture may occur and be a presenting manifestation, which may mimic deep venous thrombosis with calf swelling and pain. Joints may be warm, but the overlying skin is not usually erythematous. Affected joints may be uncomfortable, and patients may have limited range of motion due to the size of an effusion.

Serum serology, particularly IgG antibody response, is the key diagnostic test for Lyme arthritis. Because Lyme arthritis is a late manifestation of untreated Lyme disease, high levels of anti-Borrelial antibodies are present & serology is a highly sensitive test.

In addition, patients with Lyme arthritis usually lack fever or systemic symptoms.

Serum serology, particularly IgG antibody response, is the key diagnostic test for Lyme arthritis. Because Lyme arthritis is a late manifestation of untreated Lyme disease, high levels of anti-Borrelial antibodies are present and serology is a highly sensitive test. Serologic testing is currently performed using a two-tier testing strategy, starting with an ELISA test followed by a confirmatory IgM and IgG immunoblot for positive ELISA tests.3 In Lyme arthritis, IgG immunoblots are always positive (with five or more IgG bands). Moreover, a highly expanded immune response is seen, often with 7–10 IgG bands. IgM bands may be present as well, but are not required for the diagnosis, and the presence of an IgM antibody response alone should not be used to confirm the diagnosis of Lyme arthritis.

ESR and CRP levels may be elevated in some patients with Lyme arthritis. Hematologic abnormalities, such as thrombocytopenia or anemia, are atypical and—along with other symptoms, such as fever—could raise concern for other tick-borne co-infections.

Synovial fluid analysis is important to exclude other causes of oligoarthritis, including crystalline disease and other infectious agents. Synovial fluid white cell counts in Lyme arthritis are in the 10,000–25,000 white blood cells/µL range. Culture and gram stain are not available for B. burgdorferi but may be performed to evaluate for typical bacterial pathogens. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing for B. burgdorferi DNA is often positive prior to antibiotic treatment and may help confirm the diagnosis.

Serologic testing is not validated for use on synovial fluid, and measurement of Lyme antibody responses in joint fluid is not recommended.

Imaging studies are not required for the evaluation of Lyme arthritis. However, plain films may show effusion. Ultrasound or MRI can be used to evaluate for synovitis and tendinitis, and for diagnosis of Baker’s cysts. Radiographic erosions are rare in Lyme arthritis.

Photo 3: The patient has obvious swelling in the right knee.

The initial treatment of Lyme arthritis per the Infectious Diseases Society of America guideline is oral antibiotics, typically 100 mg of doxycycline twice daily by mouth or 500 mg of amoxicillin three times daily by mouth for a 28-day treatment course.4 In patients with mild persistent arthritis or recurrent synovitis after initial treatment, a second course of oral antibiotics is recommended. For patients with moderate to severe arthritis after 28 days of antibiotic therapy, intravenous (IV) antibiotics, typically IV ceftriaxone, are recommended.

Biomarkers to demonstrate the infection has been cured are currently lacking. Synovial fluid PCR is used by some clinicians to monitor therapy; however, a positive PCR may reflect residual nucleic acid and may not necessarily indicate ongoing active infection. Serum serology may also remain positive for many years after successful treatment of Lyme arthritis, and a positive serology is not a measure of active infection.

A subset, approximately 10%, of patients with Lyme arthritis has ongoing proliferative synovitis despite two to three months of oral and IV antibiotic treatment.5 Histologically, this type of arthritis is similar to other forms of chronic inflammatory arthritis, such as rheumatoid arthritis. Persistent infection has not been demonstrated from synovectomy tissue samples in patients who have received at least two weeks of IV antibiotics as part of their therapy. This condition, called antibiotic-refractory, post-infectious Lyme arthritis, seems to be an immune-mediated process characterized by high levels of interferon gamma and infection-induced autoimmunity. Both host and pathogen factors may influence this outcome.

We treat antibiotic-refractory, post-infectious Lyme arthritis patients with disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (DMARDs), including methotrexate and hydroxychloroquine.6 We have also managed post-infectious Lyme arthritis with tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitors. Intra-articular steroid injections and NSAIDs may also benefit patients with milder cases, and steroid injections have been particularly beneficial in the pediatric population. Synovectomy may also be a therapeutic option for patients with monoarthritis. Patients respond quite well to DMARD therapy without signs of recurrence of infection.

In contrast to rheumatoid arthritis, which requires long-term—often lifetime—treatment, post-infectious Lyme arthritis resolves over time, and long courses of DMARDs are not needed. We typically treat Lyme arthritis patients with DMARDs for only 6–12 months.

Finally, we have seen patients develop other forms of autoimmune arthritis, such as rheumatoid arthritis or spondyloarthropathy, following previously treated Lyme disease, and this possibility can be considered in patients with persistent arthritis despite antibiotic treatment.7

Although post-treatment Lyme syndrome seems to affect patients with early or neurologic Lyme disease more frequently than those with Lyme arthritis, diffuse pain or neurocognitive symptoms despite resolution of inflammatory arthritis would suggest this problem.8

For all patients with Lyme arthritis, physical therapy is an important adjunctive treatment to prevent quadriceps atrophy and preserve function. However, the majority of patients with Lyme arthritis achieve good long-term clinical outcomes.

Case Outcome

We treated the patient in the opening scenario with a one-month course of 2 g of ceftriaxone via IV daily. During the treatment, he noted improvement in his knee swelling and had only mild residual swelling at completion. An NSAID was started.

Several weeks later, the patient’s right knee swelling recurred, and some milder swelling in his right ankle developed. He had partial improvement with a steroid injection in the knee. Methotrexate was started at a dose of 15 mg/week, along with folic acid.

He markedly improved with methotrexate treatment by the six-week visit, and inflammatory tests that had been persistently elevated normalized.

After three months, his methotrexate dose was lowered, and it was stopped completely after five months without any recurrence of his arthritis.

John N. Aucott, MD, is the director of the Johns Hopkins Rheumatology Lyme Disease Research Center, and an associate professor of medicine in the Division of Rheumatology and Department of Medicine at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore. He is also the immediate past chair of the HHS Tick-Borne Disease Working Group of the Office of HIV/AIDS and Infectious Disease Policy, Office of the Assistant Secretary of Health, Department of Health and Human Services (https://www.hhs.gov/ash/advisory-committees/tickbornedisease).

John N. Aucott, MD, is the director of the Johns Hopkins Rheumatology Lyme Disease Research Center, and an associate professor of medicine in the Division of Rheumatology and Department of Medicine at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore. He is also the immediate past chair of the HHS Tick-Borne Disease Working Group of the Office of HIV/AIDS and Infectious Disease Policy, Office of the Assistant Secretary of Health, Department of Health and Human Services (https://www.hhs.gov/ash/advisory-committees/tickbornedisease).

Sheila L. Arvikar, MD, is a rheumatologist in the Division of Rheumatology, Allergy, and Immunology and the Center for Immunology and Inflammatory Diseases at Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH), Boston. She staffs the MGH Lyme arthritis clinic with Allen Steere, MD. She receives support from the Global Lyme Alliance for her clinical research studies in Lyme arthritis.

Sheila L. Arvikar, MD, is a rheumatologist in the Division of Rheumatology, Allergy, and Immunology and the Center for Immunology and Inflammatory Diseases at Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH), Boston. She staffs the MGH Lyme arthritis clinic with Allen Steere, MD. She receives support from the Global Lyme Alliance for her clinical research studies in Lyme arthritis.

References

- Schwartz AM, Hinckley AF, Mead PS, et al. Surveillance for Lyme Disease—United States, 2008–2015. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2017 Nov;66(22):1–12.

- Steere AC, Schoen RT, Taylor E. The clinical evolution of Lyme arthritis. Ann Intern Med. 1987 Nov;107(5):725–731.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Recommendations for test performance and interpretation from the Second National Conference on Serologic Diagnosis of Lyme Disease. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1995 Aug;44(31):590–591

- Wormser GP, Dattwyler RJ, Shapiro ED, et al. The clinical assessment, treatment, and prevention of Lyme disease, human granulocytic anaplasmosis, and babesiosis: clinical practice guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2006 Nov 1;43(9):1089–1134.

- Steere AC, Angelis SM. Therapy for Lyme arthritis: Strategies for the treatment of antibiotic-refractory arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2006 Oct;54(10):3079–3086.

- Arvikar SL, Steere AC. Diagnosis and treatment of Lyme arthritis. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2015 Jun;29(2):269–280.

- Arvikar SL, Crowley JT, Sulka KB, Steere AC. Autoimmune arthritides, rheumatoid arthritis, psoriatic arthritis, or peripheral spondyloarthritis following Lyme disease. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2017 Jan;69(1):194–202.

- Aucott JN. Posttreatment Lyme disease syndrome. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2015 Jun;29(2):309–323.