SAN FRANCISCO—“We haven’t made a lot of progress in ensuring the early diagnosis of spondyloarthritis,” said Walter Maksymowych, MD, FRCP, professor of medicine in the Division of Rheumatology at the University of Alberta and chief medical officer at CaRE (Canadian Research and Education) Arthritis, both in Edmonton.

Speaking at the California Rheumatology Alliance 2016 Medical & Scientific Meeting in May, he offered one reason for this lack of progress: an overreliance on X-ray assessments and insensitive and nonspecific lab tests, along with a failure to take advantage of such technologies as the use of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) for early diagnosis and classification.

Inflammatory-type back pain is common with lower back pain due to various causes. Spondyloarthritides, a set of chronic diseases of the joints, are diagnosed based on lab tests, imaging tests and inflammatory symptoms. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are commonly used to treat pain and inflammation, but when these don’t provide relief, doctors often prescribe disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (DMARDs) similar to those used in rheumatoid arthritis, but these are not effective.

“You can measure inflammatory markers, such as C-reactive protein, but they lack sensitivity and specificity,” Dr. Maksymowych explained. Diagnosis of spondyloarthritis by X-ray for a complex structure, such as the sacroiliac joint, doesn’t identify early changes and is unreliable until more advanced stages of the disease—at a point of functional impairment. “There’s a great deal of subjective interpretation required. It’s not surprising that rheumatologists have trouble with it,” he said.

“The shame is that there are effective treatments, but we don’t get to them soon enough because we aren’t using MRI.” There is good evidence that the sooner you treat, the more impressive the results, with the possibility for remission of symptoms. Earlier diagnosis might also mean earlier access to biologic therapies. “We might be able to slow progression of disease. Will early treatment stop spine damage? We can’t begin to explore the possibilities if we don’t make earlier diagnoses.”

Dr. Maksymowych

For Dr. Maksymowych, the MRI is the imaging modality of choice for early diagnosis of sacroiliac lesions in inflammatory back pain in settings where crucial treatment decisions are made. But interpreting MRIs for this purpose requires a level of comfort with the DICOM (Digital Imaging and Communications in Medicine) image standard for handling, storing and transmitting medical images. DICOM is the international standard for medical imaging and requires special software for the images to be seen.

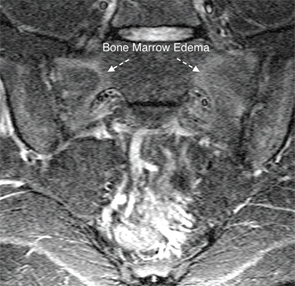

These images illustrate the two MRI sequences that can be used together to diagnose spondyloarthritis in the sacroiliac joint, as described by Dr. Maksymowych. The T1-weighted MRI scan of the sacroiliac joint in the semi-coronal plane (top) is a fat-sensitive sequence, so subcutaneous fat appears bright. This scan is abnormal because it shows two large areas of bright signal in the sacrum adjacent to subchondral bone characterized by a homogeneous appearance and a distinct border.

A STIR scan of the sacroiliac joint in the semi-coronal plane (bottom), taken from the same patient, is a water-sensitive scan with blood vessels and cerebrospinal fluid appearing bright. This scan is abnormal because it shows areas of bright signal in the subchondral bone marrow of the sacrum, a sign of bone marrow edema.

When both figures are viewed together, you can see that the area of bone marrow edema surrounds the area of fat metaplasia on the T1W scan—typical of inflammation that is resolving, but still remains active, in a patient with spondyloarthritis.

DICOM uses a large, uncompressed (5 to 10 megabyte) file format for medical images that are too large to send by email. It’s designed to allow consistent communication between scanners and the Picture Archiving and Communication System (PACS) that archives and allows retrieval of DICOM images. “DICOM viewers used by radiologists are too complicated for our purposes, and rheumatologists need something simpler. My organization, CaRE Arthritis, has developed a simplified DICOM viewer that is intuitive and doesn’t take very long to master,” he said.

Collaboration between Rheumatology & Radiology

Dr. Maksymowych strongly advocates that the rheumatologist and radiologist, who historically have occupied separate silos in healthcare, work together more closely. “The radiologist doesn’t see a lot of this particular condition, and rheumatologists, in their own silo, often don’t understand the role of MRI. They need to learn the terminology in order to have informed discussions with the radiologist,” he said. This application of MRI hasn’t been introduced into the rheumatology medical curriculum. “We don’t have trainees being exposed to the technology, and rheumatologist trainers aren’t familiar enough with it to teach it. So it becomes a vicious cycle,” he said.

“We’re not talking about transforming rheumatologists into radiologists, but we need closer interaction and improved communication. Once the rheumatologist understands this, the pace of dialogue with the radiologist really accelerates,” he added, even to the point of requesting appropriate MRI scans for the diagnostic evaluation of spondyloarthritis.

Combining 2 MRI Sequences

Using MRI images of sacroiliac joints, Dr. Maksymowych showed the audience at CRA two different, complementary sequences of MRI scans. The T1-weighted, fat-sensitive sequence is one of the basic types of MRI scan, with fat appearing bright, as in the subcutaneous tissues. This scan provides details of the anatomy of the sacroiliac joints and is the primary type of MRI used to evaluate structural lesions such as erosion. The STIR (Short Tau Inversion Recovery) sequence is typically used to null the signal from fat and detects water, such as edema in the bone marrow, which is evidence of active inflammation and, with concomitant structural lesions, highly suggestive of axial spondyloarthritis.

“We combine and synthesize information from the T1 and STIR scans to make a contextual interpretation of the information provided by MRI. Both sequences are important to diagnosis,” he said. The unfolding of events in the sacroiliac joint typically starts with inflammation just beneath the subchondral bone. After the inflammation has resolved, then what’s left is erosion of bone and fat metaplasia, a feature of repair in spondyloarthritis. “Then we see the development of new bone.” There is a difference between physiological fat and pathological fat metaplasia, which is distinguished on the MRI from normal, physiological fat by the presence of a distinct border, homogeneity, and proximity to subchondral bone, Dr. Maksymowych explained. This fat metaplasia is a key intermediary in the pathway from inflammation to the development of sacroiliac joint ankylosis on the MRI.

“The T1 sequence gives excellent detail around anatomy—beautiful contrast between cortical bone and underlying marrow,” he said, while the STIR allows identification of inflammation. Together, the two image sequences give information about where the inflammation is, the presence of repair tissue and erosion of bone. “All of these things together should enhance your confidence in the diagnosis.”

This kind of MRI-facilitated diagnosis can also have an impact on the patient, Dr. Maksymowych said—especially if the rheumatologist is able to show the visual evidence of active disease on the MRI images during the office visit. “It is an effective way of making the point that people need to take their medications if they want effective control of this disease. When they see the actual picture, it can have a huge impact on the problem of adherence to medication,” he explained.

“But the effective use of MRI in routine clinical practice for evaluation of spondyloarthritis requires a specific imaging protocol and hands-on training for both rheumatologists and radiologists,” Dr. Maksymowych said. “Basic aspects of MRI should be a mandatory component of the rheumatology curriculum.”

Larry Beresford is an Oakland, Calif.-based freelance medical journalist.