Brian McCabe, MD, an otolaryngologist at the University of Iowa, Iowa City, was puzzled. A patient who had undergone surgery to remove diseased cells in the mastoid bones behind both ears returned to have the structures cleaned. In the intervening weeks, however, the patient’s hearing loss had rapidly progressed until the individual was deaf in both ears.

Brian McCabe, MD, an otolaryngologist at the University of Iowa, Iowa City, was puzzled. A patient who had undergone surgery to remove diseased cells in the mastoid bones behind both ears returned to have the structures cleaned. In the intervening weeks, however, the patient’s hearing loss had rapidly progressed until the individual was deaf in both ears.

In the process of cleaning one of the patient’s mastoids, Dr. McCabe saw an unusual lesion; a biopsy was consistent with vasculitis. In response, the doctor put his patient on cyclophosphamide, then considered a state-of-the-art immune suppressant. Remarkably, the patient’s hearing gradually recovered.

In a seminal study that presented a composite case report of 18 patients seen over a 10-year period, Dr. McCabe sketched the broad outlines of this highly unusual inner ear disease.1 The condition typically involved both ears, and the rapidly progressive loss of hearing occurred over a period of weeks to months, instead of the hours-to-days or years-long decline seen with other kinds of hearing loss.

“We propose the term autoimmune sensorineural hearing loss [SNHL] on the basis of its laboratory test characteristics and specifics of its response to treatment,” Dr. McCabe wrote.

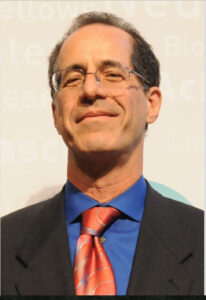

“Prior to that, there was no evidence that there was such a thing as autoimmune inner ear disease,” says Jay Rubinstein, MD, PhD, the Virginia Merrill Bloedel Chair of Otolaryngology and Bioengineering and director of the Bloedel Hearing Research Center at the University of Washington, Seattle.

In the 45 years since Dr. McCabe’s description of the condition—initially named for him—this rare form of hearing loss is still commonly misdiagnosed and has so far defied efforts to understand its underlying pathophysiology.

“There has been lots and lots of immunology research on the ear, but there’s been no good pathophysiologic explanation of how you get from the immune-related inflammation to the rapidly progressive [hearing] loss,” says Dr. Rubinstein.

The lack of good animal models for the condition has conspired against the kinds of research needed to lay out the disease pathway.

“There are a lot of tests you can do that have been proposed,” says Dr. Rubinstein, who inherited Dr. McCabe’s practice as a neurotology fellow at the University of Iowa. “None of them are really reliable. The only reliable test is the patient comes in with rapidly progressive bilateral SNHL, and you put them on high-dose prednisone and their hearing responds to that.”

Fortunately for patients, the condition is often fully reversible.

Rapidly Progressing Symptoms

The condition is also called autoimmune inner ear disease, autoimmune cochleopathy or immune-mediated cochleovestibular disease. In contrast to defective sound transmission through the external ear, tympanic membrane or middle ear, which has been associated with conductive hearing loss, autoimmune SNHL has been linked to dysfunction in the inner ear, vestibulocochlear nerve or central processing centers of the brain.2

Interestingly, about half of patients report unilateral hearing loss at presentation. Audiological tests, however, demonstrate bilateral, if often asymmetrical, involvement in the overwhelming majority of cases. Although the suite of other symptoms can vary, patients also commonly report tinnitus, aural fullness, generalized imbalance, motion intolerance, ataxia and low-grade vertigo. One important clue is the rapid progression of such symptoms.

“Genetically determined hearing loss produces slowly progressive hearing loss that occurs over months to years. Sudden hearing loss occurs over the course of 24 hours,” Dr. Rubinstein says. “It’s really only autoimmunity that we know of that produces hearing loss in weeks to months.”

Importantly, this hearing loss can accompany other autoimmune symptoms as well, especially the eye inflammation typical of Cogan syndrome in young to middle-aged adults.

Dr. Rubinstein saw several such patients during his residency at Massachusetts Eye and Ear, where David G. Cogan, MD, first described the condition named after him in 1945. The simultaneous and similarly progressing eye and ear symptoms helped link both to an underlying autoimmune disorder. In a review of 60 Cogan syndrome patients seen at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., roughly half eventually lost all hearing, although most were successfully treated with cochlear implants.3 Granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA) can affect the middle ear and mastoid bone and drive autoimmune inner ear disease as well. A recent review and meta-analysis likewise found that autoimmune SNHL is “highly prevalent” in patients with Sjögren’s disease, with a pooled prevalence of 43%.4

“There are many other autoimmune conditions where it would not be unusual to also see rapidly progressive sensory neural hearing loss,” Dr. Rubinstein says. “However, we also see this absent any known autoimmune diagnosis.”

No patient registry yet exists, although Massachusetts Eye and Ear has a bank of temporal bones donated after death by patients who had been diagnosed with autoimmune inner ear disease in life. “We have a pretty good idea of what the autoimmune inflammatory response in the inner ear looks like, but there’s no direct connection to why it’s rapidly progressive,” says Dr. Rubinstein. Similarly, he says, it’s not yet clear why the inflammatory lesion may be more responsive to corticosteroids later in its course than most other autoimmune central nervous system diseases.

Few Tests, 1 Treatment

As do rheumatologists, otolaryngologists commonly treat sudden SNHL with corticosteroids. The big difference, Dr. Rubinstein says, is that these patients typically receive a one-week course followed by tapering over the second week.

“To treat autoimmune inner ear disease, you need significantly longer courses of high-dose steroids,” he says—typically for at least a month to start. “Before I subject somebody to that experience, which is incredibly unpleasant, I’ve got to be pretty confident that that’s what we’re dealing with. So I want to see evidence that the hearing loss is progressing.”

Is there a role for Hsp70 antibodies to help distinguish sudden SNHL from autoimmune SNHL? Dr. Rubinstein says unfortunately no. Although testing for the presence of Hsp70 antibodies cannot distinguish sudden from autoimmune SNHL, the test can help predict responsiveness of rapidly progressing SNHL to glucocorticoids, he notes. Periodic audiograms can help confirm that the hearing loss is indeed rapidly progressing, he adds, while magnetic resonance imaging is also routine because the loss is often asymmetric.

“When someone has asymmetric hearing loss, we always image them to look for acoustic tumors,” he says. Meningeal carcinomatosis can also cause bilateral, rapidly progressive hearing loss. “The purpose of the MRI scan is to rule out other conditions, not to rule in autoimmune inner ear disease. There’s no imaging correlate of the condition, so it’s really just based on hearing tests,” he says.

If a differential diagnosis points to autoimmune SNHL, doctors have traditionally treated patients with three months of high-dose glucocorticoids and then tapered the dose while conducting hearing tests to find the lowest possible dose that allows hearing to be maintained. Some patients can be successfully weaned from the steroids; for others, the tapering has led to flares that require ramping up the dose again.

Clinicians have periodically assessed alternatives to high-dose glucocorticoids, such as methotrexate, which has lower toxicity and fewer side effects. A few small studies have suggested methotrexate may help treat patients with refractory SNHL, although larger placebo-controlled trials haven’t found a significant benefit. One multi-center clinical trial, for example, enrolled patients who had bilateral, rapidly progressive hearing loss and had at least partially responded to a month-long dose of prednisone.5 The trial then randomized one arm of patients to methotrexate and the other to continued prednisone.

The methotrexate arm “failed miserably,” Dr. Rubinstein says. “By that point, methotrexate had become pretty popular for treating it, but the evidence was pretty clear in the trial that methotrexate didn’t help.”

A systematic review found that methotrexate “appears to be more efficacious in treating vestibular symptoms.”6 So far, no definitive evidence has emerged to suggest an efficacious non-steroidal treatment for the hearing loss.

Making the Right Referral

Even for a specialist, patients with autoimmune SNHL are fairly rare. “Let me put it this way: I more commonly see people who are erroneously diagnosed with autoimmune inner ear disease than I do people with true autoimmune inner ear disease,” says Dr. Rubinstein.

Otologists commonly misdiagnose the condition in patients with sudden SNHL, which doesn’t have rapidly progressive symptoms and typically isn’t bilateral, but can respond to glucocorticoids. The problem, according to Dr. Rubinstein, is that clinicians often refer such patients to a rheumatologist for treatment with another immune modulator before properly differentiating between the two conditions.

“They’ll be on that treatment for years,” he says. “I’ll see them, and usually they come with a pile of hearing tests, and at that point, I’ll say, ‘I think we should stop the medication that you’re on and see what happens. If it’s really autoimmune, your hearing may drop, and then we’ll know for sure, and we’ll put you back on it and you won’t have lost anything. But it might enable you to get off this relatively toxic stuff that you’re taking.’”

In an ideal setting, he says, such a patient would be referred by one of his colleagues instead of a rheumatologist. “But the classic situation [in which] a rheumatology referral is great is if a rheumatologist is treating someone for a known autoimmune condition, say rheumatoid arthritis, and then the person develops rapidly progressive hearing loss,” Dr. Rubinstein says. “That’s the perfect situation to make the diagnosis easily and get the person treated.”

Dr. Rubinstein typically doesn’t refer a patient with autoimmune inner ear disease to a rheumatologist unless he can’t get them off prednisone or they have other symptoms beyond hearing loss that are suggestive of other diseases. “It’s worth experimenting a little bit to see if there’s some other drug where, even though it’s unproven, in their particular case [may] allow them to get off steroids,” he says.

If Dr. Rubinstein strongly suspects the hearing loss is autoimmune in nature but the patient doesn’t respond to glucocorticoids, he may consult with a rheumatologist to seek alternatives. “Generally nothing works in that setting. However, that doesn’t mean I wouldn’t give it a try,” he says.

For rheumatologists, perhaps one of his biggest take-home points is this: “It’s not an emergency,” Dr. Rubinstein says. “When we treat sudden hearing loss, the thinking is that if we don’t treat it within a few weeks of onset, we lose our treatment window. That’s not true for autoimmune disease. I’ve seen people months after the onset of their hearing loss who still respond to treatment. So it’s not a ‘drop everything’ emergency where you don’t really have time to think about what you’re doing.”

That advice diverges from most rheumatological models of nerve dysfunction, such as vision loss in giant cell arteritis (GCA) and mononeuritis in vasculitis, in which tissue ischemia leads to rapid and irreversible nerve damage. Dr. Rubinstein can’t say how the underlying inflammatory lesion of autoimmune SNHL might differ from those rheumatological conditions. Nevertheless, he says the expanded treatment window can allow rheumatologists to fully consider their approach.

“You have plenty of time to make a referral. It’s not an emergency, and it’s really easy to hurt people,” Dr. Rubinstein says. “These drugs are not benign.”

Bryn Nelson, PhD, is a medical journalist based in Seattle.

References

- McCabe BF. Autoimmune sensorineural hearing loss. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1979 Sep–Oct;88(5):585–589.

- Mijovic T, Zeitouni A, Colmegna I. Autoimmune sensorineural hearing loss: The otology–rheumatology interface. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2013 May;52(5):780–789.

- Gluth MB, Baratz KH, Matteson EL, et al. Cogan syndrome: A retrospective review of 60 patients throughout a half century. Mayo Clin Proc. 2006 Apr;81(4):483–488.

- Paraschou V, Partalidou S, Siolos P, et al. Prevalence of hearing loss in patients with Sjögren syndrome: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Rheumatol Int. 2023 Feb;43(2):233–244.

- Harris JP, Weisman MH, Derebery JM, et al. Treatment of corticosteroid-responsive autoimmune inner ear disease with methotrexate: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2003 Oct 8;290(14):1875–1883.

- Breslin NK, Varadarajan VV, Sobel ES, Haberman RS. Autoimmune inner ear disease: A systematic review of management. Laryngoscope Investig Otolaryngol. 2020 Dec;5(6):1217–1226.