In December 2009, we encountered a 17-year-old male who was dying from a recently diagnosed catastrophic disease. He was previously healthy and athletic. He was a patient in the intensive care unit (ICU) with decompensated vital signs, following an exploratory laparotomy for polybacterial peritonitis and sepsis from gastrointestinal (GI) microperforations. He was deteriorating despite treatment with immune intravenous globulin (IVIG) and broad-spectrum antibiotics.

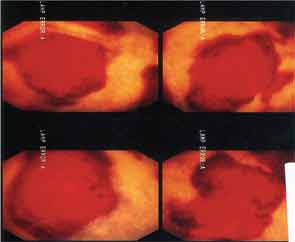

Prior to his presentation in the ICU, the patient had a two-year history of developing innumerable, multiplying avascular slightly depressed porcelain-like skin lesions surrounded by an erythematous rim. These were present primarily on his chest and abdomen. He was diagnosed with malignant atrophic papulosis (MAP), based on the skin biopsy findings and clinical history, in August 2009 (see Figure 1). Abdominal pain and other nonspecific GI symptoms had started six months earlier. Endoscopy was performed, which showed gastritis and an erythematous mucosa of the sigmoid colon, rectosigmoid junction and splenic flexure. Because of the severity of his pain, an exploratory laparotomy was performed, which showed multiple small 5–8 mm ulcerated lesions throughout the small bowel (see Figure 2). Further evaluation for an underlying rheumatologic disease was negative.

With the patient’s health steadily deteriorating, we desperately reached out to the medical community. We heard of a similar patient who had responded to treatment with eculizumab. We were able to obtain eculizumab on a compassionate-use basis, and he had an almost immediate response. Soon after, his abdomen was closed; it had been left partially opened due to abdominal compartment syndrome. Repeat echocardiogram showed resolution of the pericardial effusion, and the chest X-ray also showed improvement.

He continued to receive eculizumab infusions every other week and self-administered subcutaneous enoxaparin daily. He improved to the point that he gained back all the weight he had lost and was exercising again. Eventually, he returned to school, work and enjoying his life with family and friends.

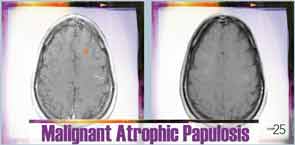

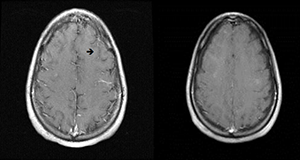

Six months after discharge, he developed gross hematuria and severe flank pain (enoxaparin was stopped). Cystoscopy demonstrated multiple lesions suggestive of MAP (see Figure 3). The dose of eculizumab was increased due to the concern that the dose reaching his bladder was subtherapeutic. The patient developed neurological symptoms, including perioral numbness and tingling sensation around his distal fingers. A magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) study of the brain was concerning for left frontal lobe vasculitis, as well as the presence of a 1 mm thick subdural hematoma. The dose of eculizumab was increased to weekly injections, and he was started on levetiracetam and aspirin.

A few months later, the patient developed a small bowel obstruction as a result of adhesions. His hospitalization was complicated by the development of pleural effusion requiring thoracentesis. He also experienced a 30 lb. weight loss and severe deconditioning, requiring total parenteral nutrition for bowel rest. Additionally, he developed a new supraventricular tachycardia.

Once again the search for answers started.

Lesson Learned from a 2nd Patient

With the unique nature of MAP skin lesions, we were able to identify similar lesions on another patient previously diagnosed with an overlap syndrome with features of systemic lupus erythematous and systemic sclerosis. The skin lesions were biopsied and were reported as MAP-like lesions. Subsequently, the patient was started on subcutaneous treprostinil for treatment of her severe pulmonary hypertension. Interestingly, within three months of initiating therapy with treprostinil, her MAP-like skin lesions showed marked involution (see Figure 4).

Based on these findings, in December 2010, we were able to obtain treprostinil on a compassionate-use basis for our 17-year-old male patient. Slowly, he improved and has been maintained on a regimen of treprostinil, eculizumab and aspirin.

Repeat MRI of the brain showed complete resolution of brain lesions (see Figure 5). He continues to develop some skin lesions, but they involute more quickly and remain smaller in size compared with presentation prior to treatment.

A 3rd Patient

Our 17-year-old patient’s sister was found to have biopsy-proven MAP skin lesions. She underwent exploratory laparoscopy to evaluate complaints of abdominal pain, and no serosal lesions were seen. The pain spontaneously resolved. It appears that she has cutaneous disease only.

What Is Malignant Atrophic Papulosis?

MAP is an uncommon thrombo-occlusive vasculopathy with characteristic skin lesions.1 Similar lesions can affect internal organs, such as the GI tract, central nervous system, pericardium and bladder.2 Thrombotic complications with characteristic infarcted zones can be seen on histopathology.3,4 Cutaneous-only involvement has been described. Conversely, previously reported systemic disease has been fatal.

Recent reports noted that systemic symptoms were recorded in nearly one-third of the patients.2 Systemic MAP involves small- and medium-size arteries.5 Transformation from cutaneous to systemic can occur within months to years following the onset of dermatologic manifestations.6 Typically, around 30 skin lesions are seen in an average patient, but the presence of more than 600 has been described.7 Lesions may start as papules and persist as such, or they may develop a central area of necrosis that replaces the papule.8

The diagnosis is clinicopathologic because there are no specific laboratory tests.9

The most common cause of death is sepsis due to peritonitis and perforation (occurring in approximately 60% of reported cases) developing within two to three years of internal organ involvement.10

The etiology of MAP is unknown.11 Although there seems to be a genetic predisposition, no gene has been identified.11-13 MAP can be seen independently, or there may be MAP-like lesions seen in other connective tissue diseases (CTDs).6,10 There have been deposits consisting of activated complement pathway proteins, C5b-9, found in the tissues of patients with dermatomyositis, scleroderma and MAP.14-18 Dermal fibrosis can also be seen in each of these three diseases.17 A prior viral exposure has been theorized.14

MAP is a rare, life-threatening disease. With the most current findings & investigations, we may be able to bring some hope to patients—or at least open the door for further investigation.

History

MAP was first described by W. Köhlmeier, an Austrian physician, in 1941.2 Later, Robert Degos, MD, a French dermatologist, reported a 45-year-old plumber with typical MAP skin lesions who died of GI complications shortly after being diagnosed. At autopsy, the small intestine lesions were found to be similar to the skin lesions, with thrombi deposited in the venules.4 In 1948, Degos changed the name of the disease to papulose atrophiante maligne or malignant atrophic papulosis.19

Incidence & Prevalence

Approximately 200 cases have been reported in the literature. However, it is thought that many cases go unreported. Most patients are Caucasian, with a peak incidence in the third decade of life, but there are a few reports in children. There is a 3:1 male–female ratio.11,20,21 The cutaneous form of the disease is mostly seen in women.22 Familial forms have also been described.23

Histopathology

The skin lesions range from 0.3–1.0 cm in size and appear as pink to brown papules with an atrophic, porcelain-white center and erythematous, telangiectatic/violaceous border/rim.24,25 Lesions look similar in all organs.26,27 The classic histopathological findings consist of wedge-shaped infarctions with collagen degradation, endothelial proliferation and occlusion by thrombi.25 Early lesions can have perivascular inflammatory infiltrates with interstitial mucin deposition.5 There may be swelling and proliferation of endothelial cells beneath the zones of necrobiosis.5 Histologically, there is no difference in the histopathology of lesions in those with limited (cutaneous only) or the systemic form of the disease.11

Transformation from cutaneous to systemic MAP can occur within months to years following the onset of dermatologic manifestations. Systemic MAP involves small- & medium-size arteries.

Prior Medical Treatment

Multiple medication regimens had been suggested, although none was found to be effective. These include IVIG, ASA, dipyridamole, warfarin, heparin, azathioprine, tacrolimus, cyclophosphamide, bevacizumab and infliximab.28-31

Eculizumab

Eculizumab is a humanized monoclonal antibody that binds to human C5 complement protein and inhibits cleavage to C5a and C5b. This inhibition prevents both generation of the membrane attack complex (MAC) and the proinflammatory effects of C5a. Additionally, eculizumab has potent antianaphylatoxin and antichemotaxin effects. Patients should receive meningococcal vaccination at least two weeks prior to treatment.5,34

Treprostinil

Treprostinil is a long-acting prostacyclin analog that may help heal ischemic wounds and decrease pain due to ischemia; it also has some antiplatelet effects and may increase the number and angiogenic potential of endothelial progenitor cells.36,38 It had previously been observed that a patient with systemic sclerosis treated with treprostinil noted improvement of her MAP lesions.

The most common cause of death is sepsis due to peritonitis & perforation, developing within two to three years of internal organ involvement.

Lessons Learned

MAP is a rare, life-threatening disease. With the most current findings and investigations, we may be able to bring some hope to patients—or at least open the door for further investigation. Our first patient has survived four years to date with the current treatment. While on this dual therapy, he has developed atrial fibrillation and undergone cardiac ablation and, more recently, has had recurrent pleural effusion.

The burden of this disease requires an integrated, multidisciplinary team. Without communications with other healthcare providers, we may never have learned of the patient who was successfully treated with eculizumab and our patient may not have survived. Because MAP can affect multiple organ systems, management of this disease requires many specialists to orchestrate care of these patients.

Conclusion

In summary, MAP is a rare and highly aggressive disease. However, the unique nature of the skin lesions provides clinicians with an important clinical clue that can establish the diagnosis.

We are currently developing a national MAP registry. We hope to include all cases of cutaneous and systemic disease to better document the natural history of the disease and the long-term response to therapeutic interventions. From extensive personal communications that started after we treated our first patient, we learned of several other cases that went unreported. This makes awareness of MAP of vital interest to clinicians who care for patients with systemic diseases.

Aixa Toledo-Garcia, MD, is a board-certified rheumatologist at the Center for Rheumatology and co-medical director of the Steffens Scleroderma Center in Albany and Saratoga Springs, N.Y. She is working with other physicians to formulate new and effective diagnostic and therapeutic interventions for MAP.

Jessica Farrell, PharmD, is a clinical pharmacist at The Center for Rheumatology, co-director of the Steffens Scleroderma Center and assistant professor at Albany College of Pharmacy and Health Sciences in Albany, N.Y. She is currently serving as a member of the ARHP Practice Committee and the ACR/ARHP Drug Safety Subcommittee.

Lee Shapiro, MD, is director of the Steffens Scleroderma Center in Albany and Saratoga Springs, N.Y., and clinical professor at Albany Medical College.

References

- Assier H, Chosidow O, Piette JC, et al: Absence of antiphospholipid and anti-endothelial cell antibodies in malignant atrophic papulosis: A study of 15 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995:33(5 Pt 1):831–833.

- Theodoris A, Konstantinidou A, Makrantonaki E, et al: Malignant and benign forms of atrophic papulosis (Köhlmeier-Degos disease)—Systemic involvement determines the prognosis. Br J Dermatol. 2014 Jan;170(1):110–115.

- Molenaar WM, Rosman JB, Donker AJ, et al: The pathology and pathogenesis of malignant atrophic papulosis (Degos’ disease). A case study with reference to other vascular disorders. Pathol Res Pract. 1987;182(1):98–106.

- Degos R: Malignant Atrophic Papulosis. Br J Dermatol. 1979;100(1):21–35.

- Magro C, Wang X, Garrett-Bakelman F, et al: The effect of Eculizumab on the pathology of malignant atrophic papulosis. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2013; 8:185.

- Ortiz A, Ceccato F, Albertengo A, et al: Degos cutaneous disease with features of connective tissue disease. J Clin Rheumatol. 2010;16(3):132–134.

- Moulin G, Barrut D, Franc MP, et al: [Familial Degos atrophic papulosis (mother-daughter)] (article in French). Ann Dermatol Venereol. 1984;111(2):149–155.

- Fernandez-Perez E, Grabscheid E, Scheinfeld NS: A case of systemic malignant atrophic papulosis (Köhlmeier-Degos’ disease). J Natl Med Assoc. 2005;97(3):421–425.

- Vicktor C, Schultz-Ehrenburg U: [Malignant atrophic papulosis (Köhlmeier-Degos): Diagnosis, therapy and course] (article in German). Hautarzt. 2001, 52(8):734–737.

- Heymann W: Degos disease: Considerations for reclassification. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;61(3):505–506.

- Theodoridis A, Makrantonaki E, Zouboulis CC: Malignant atrophic papulosis (Köhlmeier-Degos disease)—A review. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2013;14;8:10.

- Habbema L, Kisch LS, Starink TM: Familial malignant atrophic papulosis (Degos’ disease)—Additional evidence for heredity and a benign course. Br J Dermatol. 1986;114(1):134–135.

- Kisch LS, Bruynzeel DP: Six cases of malignant atrophic papulosis (Degos’ disease) occurring in one family. Br J Dermatol. 1984;111(4):469–471.

- Dyrsen ME, Iwenofu OH, Nuovo G, et al: Parvovirus B19-associated catastrophic endothelialitis with a Degos-like presentation. J Cutan Pathol. 2008;35 Suppl 1:20–25.

- Magro CM, Poe JC, Kim C, et al: Degos disease: A C5b-9/interferon-α-mediated endotheliopathy syndrome. Am J Clin Pathol. 2011;135(4):599–610.

- Magro CM, Iwenofu OH, Kerns MJ, et al: Fulminant and accelerated presentation of dermatomyositis in two previously healthy young adult males: A potential role for endotheliotropic viral infection. J Cutan Pathol. 2009;36(8):853–858.

- Magro CM, Drysen M, Kerns MJ: Cutaneous lesions of dermatomyositis with supervening fibrosis. J Cutan Pathol. 2008;35(1):31–39.

- Magro CM, Nueovo G, Ferri C, et al: Parvoviral infection of endothelial cells and stromal fibroblasts: A possible pathogenetic role in scleroderma. J Cutan Pathol. 2004;31(1):43–50.

- Chave TA, Varma S, Patel GK, et al: Malignant atrophic papulosis (Degos’ disease): Clinicopathological correlations. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2001;15(1):43–45.

- Pinault AL, Barbaud A, Weber-Muller F, et al: [Benign familial Degos disease] (article in French). Ann Dermatol Venereol. 2004;131(11):989–993.

- Wilson J, Walling HW, Stone MS: Benign cutaneous Degos disease in a 16-year-old girl. Pediatr Dermatol. 2007;24(1):18–24.

- Hall-Smith P: Malignant atrophic papulosis (Degos’ disease). Two cases occurring in the same family. Br J Dermatol. 1969;81(11):817–822.

- Katz SK, Mudd LJ, Roenigk HH Jr.: Malignant atrophic papulosis (Degos’ disease) involving three generations of a family. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997;37(3 Pt 1):480–484.

- Torrelo A, Sevilla J, Mediero IG, et al: Malignant atrophic papulosis in an infant. Br J Dermatol. 2002;146(5):916–918.

- Chung HY, Trendell-Smith NJ, Yeung CK, et al: Degos’ disease: A rare condition simulating rheumatic diseases. Clin Rheumatol. 2009;28(7):861–863.

- Schepis C, Siragusa M, Amato C, et al: Degos’ Disease (Malignant Atrophic Papulosis) in Neurocutaneous Disorders Phakomatoses and Hamartoneoplastic Syndromes. 2008. Springer. pp. 725–730.

- Barlow RJ, Heyl T, Simson IW, et al: Malignant atrophic papulosis (Degos’ disease)—Diffuse involvement of brain and bowel in an African patient. Br J Dermatol. 1988;118(1):117–123.

- De Breucker S, Vandergheynst F, Decaux G: Inefficacy of intravenous immunoglobulins and infliximab in Degos’ disease. Acta Clin Belq. 2008;63(2):99–102.

- Caviness VS Jr., Sagar P, Israel EJ, et al: Case records of the Massachusetts General Hospital. Case 38-2006. A 5-year-old boy with headache and abdominal pain. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(24):2575–2584.

- Scheinfeld N: Malignant atrophic papulosis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2007;32(5):483–487.

- Sugai F, Sumi H, Hara Y, et al: [An autopsy case of Degos’ disease with ascending thoracic myelopathy] (article in Japanese). Rinsho Shinkeigaku. 1998;38(12):1049–1053.

- Gilaberte Y, Coscojuela C, Lezaún A, et al: Degos disease associated with protein S deficiency. Br J Dermatol. 2005;153(3):666–667.

- Passarini B, Balestri R, D’Errico A, et al: Lack of recurrence of malignant atrophic papulosis of Degos in multivisceral transplant: Insights into possible pathogenesis? J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65(2):e49–e50.

- Dmytrijuk A, Robie-Suh K, Cohen MH, et al: FDA report: Eculizumab (Soliris) for the treatment of patients with paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria. Oncologist. 2008;13:993–1000.

- Nishimura J, Yamamoto M, Hayashi S, et al: Genetic variants in C5 and poor response to eculizumab. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(7):632–639.

- Vachiéry JL, Naeije R: Treprostinil for pulmonary hypertension. Expert Rev Cardiovasc Ther. 2004;2(2):183–191.

- Liu CM, Harris RM, Hansen CD: Lesions resembling malignant atrophic papulosis in a patient with progressive systemic sclerosis. Cutis. 2005;75(2):101–104.

- Smadja DM, Mauge L, Gaussem P, et al: Treprostinil increases the number and angiogenic potential of endothelial progenitor cells in children with pulmonary hypertension. Angiogenesis. 2011;14(1):17–27.

- Crowson AN, Magro CM, Usmani A, et al: Immunoglobulin A-associated lymphocytic vasculopathy: A clinicopathologic study of eight patients. J Cutan Pathol. 2002;29(10):596–601.