SAN DIEGO—As part of a panel on systemic autoinflammatory diseases (SAIDs) at a Nov. 15 scientific session of ACR Convergence 2023, Sivia Lapidus, MD, shared context and insights on the therapeutic management of patients with these conditions.

SAN DIEGO—As part of a panel on systemic autoinflammatory diseases (SAIDs) at a Nov. 15 scientific session of ACR Convergence 2023, Sivia Lapidus, MD, shared context and insights on the therapeutic management of patients with these conditions.

The Spectrum of SAIDs

SAIDs encompass a broad swath of individually rare disorders driven by innate immune responses without autoantibodies or antigen-specific T lymphocytes. Although first applied to monogenic hereditary fever disorders encoding for inflammasome-related proteins, the term has expanded to include other monogenic and polygenic disorders that appear to be mediated by pro-inflammatory cytokines associated with innate immunity. The diseases are characterized by fever and periodic or chronic inflammation, with different manifestations in specific diseases.1

Historically, the most studied monogenic autoinflammatory conditions have been familial Mediterranean fever (FMF), tumor necrosis factor (TNF) receptor-associated periodic fever syndrome (TRAPS), mevalonate kinase deficiency (MKD) and cryopyrin-associated periodic syndromes (CAPS). The polygenic disorder PFAPA (i.e., periodic fever, aphthous stomatitis, pharyngitis and adenitis syndrome) is the most frequent autoinflammatory condition in childhood and should be considered in the differential with monogenic diseases.2

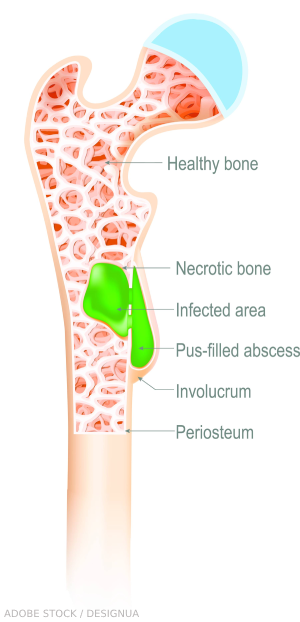

However, other autoinflammatory syndromes exist, such as Sweet syndrome and chronic recurrent multifocal osteomyelitis. Dr. Lapidus, a pediatric rheumatologist and an assistant professor of pediatrics at the Hackensack Meridian School of Medicine in Nutley, N.J., also pointed out that around a quarter of patients diagnosed with SAIDs have undifferentiated disease that can’t yet be further classified.

Clinicians must consider treatment in the context of specific diseases, which have somewhat different pathophysiology and treatment responses. To this end, EULAR and the ACR have produced useful treatment guidelines which clinicians can refer to in detail.3,4 During the talk, Dr. Lapidus shared some general considerations in their use.

Dr. Lapidus

FMF Guideline

Dr. Lapidus recommends the EULAR 2016 FMF guideline as the key article to guide therapy in these patients.3 Clinicians have used colchicine for this disorder since the 1970s, when its benefits were serendipitously discovered.1

Colchicine is still the cornerstone of therapy, and Dr. Lapidus pointed out that for most patients, it is efficacious in preventing both FMF attacks and consequent amyloidosis. In some cases, response to colchicine can be diagnostically informative. Interleukin-1 (IL-1) inhibitors can be helpful as a second-line therapy in non-responders or as an adjunct to colchicine.3

Treatment with colchicine should begin as soon as the diagnosis is made, titrated upward if attacks continue or subclinical inflammation remains.3 Dr. Lapidus recommended titrating gradually, to help minimize side effects and improve patient tolerance. A lactose-free diet can also reduce colchicine-related side effects, which may enable patients to take the higher doses they need for full response. She also noted that it can be given daily instead of in a more traditional twice a day schedule with similar efficacy.5 Given the potential toxicities of the drug, laboratory monitoring for potential side effects is also key.