Brian Goodman/shutterstock.com

CHICAGO—Despite the complicated politics surrounding medical marijuana, cannabis has a wide variety of medical benefits and potential benefits, but the risks need to be understood, said Daniel Clauw, MD, director of the Chronic Pain and Fatigue Research Center at the University of Michigan, in a session at the ACR’s 2016 State-of-the-Art Clinical Symposium.

Effects

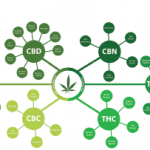

It’s important to understand the body’s endocannabinoid system to understand how the drugs work, he said. The system is a set of receptors and their natural ligands, plus enzymes that regulate them. There are two main receptor types: CB1, which mainly affects the central nervous system and the brain, and CB2, which is found in the periphery and affects the immune system and nerve cells.

The known functions of endocannabinoids are disruption of short-term memory, which can have a positive medical impact in the case of something like post-traumatic stress disorder, neurogenesis, neuroprotection, appetite increase, analgesia, immune function and stress.

Of the 80 cannabinoids found in cannabis plants, the two most important are tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) and cannabidiol (CBD). THC has mostly CB1-type effects on the central nervous system. Cannabidiol has no psychoactive effects, and it’s not clear where it binds in the body, but it appears to protect against the psychoactive effects of THC.

“We don’t know what the optimal ratio of THC to CBD is,” Dr. Clauw said. “We know it’s likely good to have some CBD.”

‘Even if we end up replacing one problem for another, [marijuana] is a safer addiction, if you will, than the opioid addiction.’ —Daniel Clauw, MD

The cannabis-based Marinol is FDA approved for nausea after chemotherapy and AIDS-induced anorexia. Cannabinoids also might have anti-spasmodic effects and neuroprotective effects. In one study, researchers examined marijuana drug-test results of people in a neurologic intensive care unit for head trauma. Those whose test for THC was positive did much better with the injuries than those who’d had a negative test. As Dr. Clauw noted, it wasn’t a randomized trial, but “the differences were pretty profound.”1

Canabinoids’ anti-inflammatory effects are being studied now at The Feinstein Institute in a trial of ajulemic acid, a cannabinoid with low potential for psychoactive effects because it has far greater selectivity for CB2 than CB1 and doesn’t get into the CNS very well. It is now being studied in lupus.

Pain Relief

Both CB1 and CB2 agonists, as well as a mixture, have been found to be effective in animal models of pain, Dr. Clauw said. They work in basically the same way opioids work—not by actually doing away with pain, but by dissociating people from the unpleasantness of pain. But much of the mechanism of action isn’t known because of the lack of NIH-funded research on the subject.

Dr. Clauw

In centralized pain, as in fibromyalgia, cannabinoids might be an especially good option, Dr. Clauw said.

“These are the pain conditions where medical marijuana may be particularly useful, because these are conditions in which opioids are ineffective and they may even make these worse,” he said.

He suggested that cannabinoids should be ahead of opioids in many algorithms for chronic pain.

“Even if we end up replacing one problem for another this is a safer addiction, if you will, than the opioid addiction,” he said.

Risk

Cannabinoids are not without risk, of course, but Dr. Clauw said, “Almost everything we know about the risk of cannabinoids is worst-case scenario because the data come from people who are recreational users of marijuana”—an approach, he said, that would be similar to studying long-time heroin users to assess the risk of Vicodin.

[Marijuana] works in basically the same way opioids work—not by actually doing away with pain, but by dissociating people from the unpleasantness of pain.

Marijuana isn’t directly lethal through, say, effects on the respiratory system, and its main potential to cause death is by causing reckless or self-destructive behavior after bringing on paranoia, he said. It’s far more dangerous in people under 25, with its dampening of motivation and risk of psychosis.

About 1 out of 10 people becomes dependent on marijuana.

“Dependence is a bit of an issue,” Dr. Clauw said. But of all the drugs that are abused, it seems to be the least addictive, he added.2

Practicalities

Dr. Clauw offered some practical views on using marijuana in medicine. He cautioned that it can’t be denied that physicians prescribing an approved cannabinoid, such as Marinol for chronic pain, are taking a risk in that they’re prescribing a controlled substance off-label, which is theoretically illegal.

He urged the use of oral forms, such as baked goods or teas, because it’s much easier to get to the levels needed without having drug levels spike. Recreational users looking for a high use much more than is needed for a therapeutic effect for pain relief.

“Most people that are legitimately medicinally using marijuana for pain don’t get high, don’t get the munchies,” he said. “[Oral] is far the preferred route of administration for someone legitimately using marijuana as an analgesic.”

Dr. Clauw also suggested that an emphasis on marijuana’s lower risk profile compared with opioids might be a way for it to gain greater acceptance in medicine.

“If that’s how we have to get it more generally accepted in the United States,” he said, “then I’m okay with that.”

Thomas R. Collins is a freelance medical writer based in Florida.

References

- Nguyen BM, Kim D, Bricker S, et al. Effect of marijuana use on outcomes in traumatic brain injury. Am Surg. 2014 Oct;80(10):979–983.

- Nutt D, King LA, Saulsbury W, et al. Development of a rational scale to assess the harm of drugs of potential misuse. Lancet. 2007 Mar 24;369(9566):1047–1053.