Diagnosis

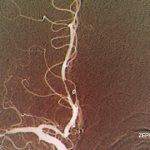

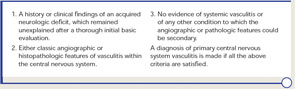

Diagnostic criteria for PCNSV were proposed by Calabrese and Mallek in 1988 on the basis of clinical experience and literature evidence (see Table 2).5 Angiographic changes indicating a high probability of vasculitis include alternating areas of smooth walled narrowing and dilated cerebral arteries, or occlusions, affecting multiple cerebral vessels in the absence of proximal vessel atherosclerosis or other recognized abnormalities (see Figure 2A). A single abnormality in multiple arteries or multiple abnormalities in a single vessel are less consistent with PCNSV.1

Because brain or spinal cord biopsy has been considered a more invasive procedure, angiography has become, by default, the more commonly used method for confirming the diagnosis in patients with suggestive clinical findings. Of note, angiographic changes typical of vasculitis may be seen in nonvasculitic conditions such as vasospasm, CNS infections, lymphomas, cerebral arterial emboli, and atherosclerosis.6,7

Among pathologically documented cases, cerebral angiography may be normal because vascular abnormalities in small vessels can be beyond the resolution of angiography.8 Overall, the sensitivity of angiography varies between 40% and 90%, while the specificity has shown to be as low as 30%.1,9 It is important to emphasize that the diagnosis of PCNSV should not be based on positive angiography alone and that angiography results should always be interpreted in conjunction with clinical, laboratory, and MRI findings.

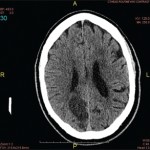

Magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) is a useful modality in the initial investigation of suspected PCNSV (see Figure 2B). However, MRA is less sensitive than conventional angiography in detecting lesions that involve the posterior circulation and distal vessels.1,10 In cases with normal MRA but a high suspicion for PCNSV, cerebral angiography should be performed.

PCNSV is unlikely in the presence of a normal MRI. Several studies have reported MRI abnormalities in close to 100% of cases.1,9 Abnormal findings on MRI are nonspecific and may include cortical and subcortical infarction, parenchyma and leptomeningeal enhancement, intracranial hemorrhage, tumor-like mass lesions, and nonspecific areas of increased signal intensity on FLAIR or T2-weighted images.

Wall thickening and intramural contrast enhancement could be specific findings in patients with active cerebral vasculitis affecting large arteries. Occasionally, enhancement may be marked and extend into the adjacent leptomeningeal tissue (perivascular enhancement).11,12 High-resolution 3T contrast–enhanced MRI may be able to differentiate enhancement patterns of intracranial atherosclerotic plaques (eccentric), inflammation (concentric), and other wall pathologies. However, the sensitivity and specificity of this technique remains to be determined.13