Over the past decade, we have witnessed increasing optimism for the outcome of patients diagnosed with rheumatoid arthritis (RA). This feeling has resulted from advances in therapeutics, which include the more aggressive use of standard disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) and the biologic agents that now are used to treat hundreds of thousands of patients around the world.1,2 Unfortunately, there are segments of the RA population that have not been able to receive these treatments, either on the basis of access or on the basis of co-morbidities that may increase the likelihood of therapeutic toxicities. Of these co-morbidities, infection with hepatitis C represents a serious and growing problem.

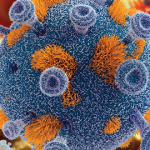

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) is a global pathogen, infecting an estimated 170 million people worldwide, and is the most common blood-borne chronic viral infection in the United States. It has been estimated that 3.9 million Americans have been exposed to the virus, with 2.9 million believed to be chronically infected.3 While accurate data on the co-association of RA and HCV are limited, it has been estimated that there are likely around 40,000 RA patients with chronic HCV infection.4 For these patients and their rheumatologists, there are serious challenges in deciding on a therapeutic plan. We have phrased these challenges as a series of questions involving issues of screening, drug selection, referral, and our overall role in the treatment teams of such patients. Fortunately, the situation is not dire and recent advances in both rheumatology and hepatology are offering new hope to these patients.

HCV—A Primer for Rheumatologists

The first challenge in evaluating a patient with possible RA and HCV infection is having a thorough understanding of the underlying infection and where the patient may belong in its natural history. Most patients with HCV infection are asymptomatic, whereas those with symptoms have mainly nonspecific complaints, such as fatigue. The transmission and risk for acquiring HCV is primarily through exposure to contaminated blood (i.e., though intravenous drugs and blood products before 1992), but high-risk sexual activity and other behaviors also pose risks (see Table 1, p. 17). Importantly, analysis of prevalence of HCV infection across age, sex, race, and geographic regions shows that infection is not constant across populations. Thus, a rheumatologist working with patient populations at increased risk (e.g., drug users, inner-city inhabitants, etc.) may be seeing HCV in their RA population at drastically increased rates. Point prevalence studies performed at several urban VA Medical Centers have revealed 11% to 40% of inpatients and outpatients are HCV seropositive.5