Over the past decade, we have witnessed increasing optimism for the outcome of patients diagnosed with rheumatoid arthritis (RA). This feeling has resulted from advances in therapeutics, which include the more aggressive use of standard disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) and the biologic agents that now are used to treat hundreds of thousands of patients around the world.1,2 Unfortunately, there are segments of the RA population that have not been able to receive these treatments, either on the basis of access or on the basis of co-morbidities that may increase the likelihood of therapeutic toxicities. Of these co-morbidities, infection with hepatitis C represents a serious and growing problem.

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) is a global pathogen, infecting an estimated 170 million people worldwide, and is the most common blood-borne chronic viral infection in the United States. It has been estimated that 3.9 million Americans have been exposed to the virus, with 2.9 million believed to be chronically infected.3 While accurate data on the co-association of RA and HCV are limited, it has been estimated that there are likely around 40,000 RA patients with chronic HCV infection.4 For these patients and their rheumatologists, there are serious challenges in deciding on a therapeutic plan. We have phrased these challenges as a series of questions involving issues of screening, drug selection, referral, and our overall role in the treatment teams of such patients. Fortunately, the situation is not dire and recent advances in both rheumatology and hepatology are offering new hope to these patients.

HCV—A Primer for Rheumatologists

The first challenge in evaluating a patient with possible RA and HCV infection is having a thorough understanding of the underlying infection and where the patient may belong in its natural history. Most patients with HCV infection are asymptomatic, whereas those with symptoms have mainly nonspecific complaints, such as fatigue. The transmission and risk for acquiring HCV is primarily through exposure to contaminated blood (i.e., though intravenous drugs and blood products before 1992), but high-risk sexual activity and other behaviors also pose risks (see Table 1, p. 17). Importantly, analysis of prevalence of HCV infection across age, sex, race, and geographic regions shows that infection is not constant across populations. Thus, a rheumatologist working with patient populations at increased risk (e.g., drug users, inner-city inhabitants, etc.) may be seeing HCV in their RA population at drastically increased rates. Point prevalence studies performed at several urban VA Medical Centers have revealed 11% to 40% of inpatients and outpatients are HCV seropositive.5

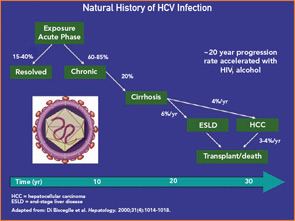

Following exposure, HCV infection resolves in an estimated 15% to 40% of patients, with the remainder progressing to chronic infection.6 The virus has a short half-life and turns over an estimated 10 to 12 billion particles per day, contributing to ongoing immune activation. Longitudinal studies suggest that, while the outcomes of patients may differ depending on study design, 75% to 80% of patients will not succumb to HCV complications and only 15% to 20% will progress to cirrhosis and die of associated complications (see Figure 1, p. 18).6 The time frame for such progression in most patients is over several decades or more. Physicians need to know these data because a detailed discussion of such issues with an infected patient can help allay fears about the disease. Of concern, however, is the small percentage of patients who rapidly progress to end-stage liver disease and its complications, including those with associated immunosuppressive illnesses (i.e., human immunodeficiency virus [HIV] infection or other immunodeficiencies) and heavy consumers of alcohol. Thus, testing and behavioral modification of alcohol consumption is recommended.

Predicting progression of liver damage is not straightforward, since there are no efficient noninvasive strategies currently widely endorsed; biopsy remains the gold standard to assess disease severity and progression.7 Newer non-invasive strategies evaluating liver fibrosis are currently being investigated, including serum fibrosis biomarkers and imaging modalities such as the transient or magnetic resonance elastography.8 Up to 30% of patients may have persistently normal or near normal liver enzymes and yet a significant portion of these individuals can have advanced fibrosis or even cirrhosis on biopsy. Viral load quantification by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) is widely available but also does not predict outcome other than response to antiviral therapy.

The standard treatment regimen for chronic hepatitis C is combination therapy with pegylated interferon-a (IFN-a) with ribavirin given for six to 12 months. This regimen achieves viral clearance in 42% to 80% of patients.7 Factors associated with a favorable response to antiviral therapy include the virus genotype (there is a better responses in genotypes -2 and -3 compared with genotype-1), low pre-treatment viral load (≤ 2×106 copies/ml), young age, and a good virologic response after three months of therapy (≥ 2-log decline in HCV RNA levels from baseline).7

Table 1: Essential Facts about HCV for the Rheumatologist

Biology

- Taxonomy: RNA virus member of the Flaviviridae family

- Size: 9.6 kb

- Replication rate: In excess of 10 billion particles per day

Epidemiology and Transmission

Globally distributed chronic infection

- 170 million infected worldwide

- 2.9 million in the United States

Modes of HCV Transmission

- IVDU or intranasal drug use

- Blood products/tissue transplants before 1992

- High-risk sexual activity

- Nosocomial or occupational transmission

- Tattoos, body piercing

- Shared personal items with infected individuals

- Mother to infant

Clinical Features

- Most frequently asymptomatic

- 15% to 40% clear infection within six months

- 60% to 85% chronically infected

- 20% with chronic HCV infection develop cirrhosis leading to hepatocellular carcinoma, decompensation, or death

- Chronically infected patients may have normal liver enzymes 30% of the time

Diagnosis

- HCV antibody by EIA as initial screen

- If EIA is positive, follow with HCV RNA

- If HCV RNA is positive, patient is chronically infected

- If HCV RNA is negative patient is probably not infected; repeat RNA testing in six to 12 months

Does HCV Infection Confound RA Diagnosis?

HCV can impede the diagnosis of RA, particularly in the early stages, in several ways. First, it is now well known that HCV infection is frequently accompanied by rheumatoid factor (RF) activity that can be of high titer; thus, false-positive RF tests should always raise the possibility of HCV infection. Secondly, patients with HCV infection can manifest a variety of articular signs and symptoms that could be confused with true RA.9 In general, HCV-infected patients have symmetric polyarthralgias more commonly than frank synovitis and erosive changes do not occur. Finally, several studies have documented that HCV infected patients have a low frequency of anti-CCP antibodies, suggesting that high-titer anti-CCP in an HCV infected patient with polyarthritis is more likely to represent true RA.

Which RA Patients Should Be Screened for HCV Infection, and How?

Screening strategies for chronic blood-borne viral infections in general (i.e., HCV, hepatitis B virus [HBV], and HIV) are controversial and ever changing and should prompt rheumatologists to reassess their own role in the patient screening process. Official recommendations for rheumatologists are limited, but the RA treatment guidelines of the ACR recommend only testing for HCV and HBV in patients at “high risk” among those being put on methotrexate or leflunomide.10 Clearly, such practices need revision. Nonbiologic DMARD therapy has not been extensively studied in the HCV infected population, but limited data suggest a high incidence of hepatotoxity with many agents traditionally thought safe.11

One cannot rationally discuss HCV screening without consideration of screening strategies for other chronic viral infections such as HBV and HIV. We now know that HBV reactivation represents a growing and potentially fatal threat to patients on all forms of immunosuppression, including both nonbiologic DMARDS and all tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitors and rituximab therapies.12 While oncologists and transplant physicians have clearly articulated guidelines, rheumatologists, as a profession, have not. We think it would be prudent to screen all patients going on to both nonbiologic and biologic DMARD therapies for HCV and HBV and, following the recent Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Guidelines, to test for HIV as well.13 Screening is inexpensive and nonpejorative and provides a wealth of useful information, not least of which could be the identification of a patient with a serious and yet highly treatable infection.

Testing for HCV is simple, with initial screening by HCV enzyme immunoassay (EIA) which has a high sensitivity and specificity. Positive EIA tests must be confirmed by detecting HCV RNA in blood by molecular amplification, most generally PCR. An EIA positive patient who is repeatedly negative by sensitive PCR for HCV RNA is considered to have either a resolved infection or a false-positive screening test. Either way, such patients are managed as if uninfected.

What Are the Safest and Most Effective Treatment Options?

Unfortunately, we cannot currently answer this question with confidence, given the limited data to guide us and the lack of serial liver biopsy studies (the gold standard) to reassure us that any form of therapy is totally safe. Many rheumatologists have suggested that conventional wisdom tells us that, given the absence of an obvious hepatotoxicity signal in the untold numbers of HCV-infected RA patients exposed to DMARD therapies, we should conclude that we are inflicting no obvious harm on our patients. Overinterpretation of such observations should be cautioned against, since the natural history of HCV infection extends over decades.

In the absence of biopsy data, at minimum, drugs with prominent hepatotoxic profiles such as methotrexate and leflunomide should be avoided in general. This is in accordance with the most recent ACR recommendations that suggest avoiding these DMARDs in all patients with chronic hepatitis C.14 Although this is a general statement, we believe that, in individual patients where there is a clear indication for treatment with these DMARDs, exceptions to these recommendations exist. Critical to the use of any DMARD in an HCV-infected patient with RA is the strong relationship between the rheumatologist, the patient, and the consulting hepatologist. We believe that, in a highly adherent patient, methotrexate or leflunomide can be started or continued if liver function is stable and there is no or minimal fibrosis in the liver biopsy.

Other available treatment options include either nonbiologic DMARDS (hydroxychloroquine, cyclosporine), which most rheumatologists consider less potent, or the newer biologic agents, which clearly alter the host immune response and thus may be harmful to patients with a chronic infection. One class of drugs for which there is a growing safety database is the TNF inhibitors. Anecdotal reports, small retrospective series, and now prospective studies, have all suggested an absence of obvious safety signals, good tolerability, and no obvious influence on underlying HCV infection.15,16 Again, in the absence of biopsy data, ultimate safety cannot be assumed. In addition to these data, a small, single-center trial of etanercept as adjunctive therapy to IFN-a and ribavirin for HCV infection provided evidence of both safety and potential efficacy.17

Based on these observations, a multicenter, randomized, placebo-controlled trial comparing standard antiviral treatment (Peg-IFNa-2b with ribavirin) to the same regimen given in conjunction with another TNF inhibitor (infliximab) is currently underway in order to assess its antiviral efficacy in patients with chronic hepatitis C (ClinicalTrials.gov, NCT00512278). This study will provide pivotal data on the risks and benefits of at least one year of TNF inhibitor exposure in HCV infected patients, as well as critically needed data on the effects of TNF inhibition on liver histology.

Thus, while limited, there appears to be more safety data on the use of TNF inhibitors in the setting of chronic HCV infection than any other class of DMARDs.15 Recently, the ACR also recommended that anti-TNF agents can be used in patients with chronic hepatitis C without evidence of decompensated liver disease.14

Data are even more limited on other biologic agents (abatacept, anakinra) because most studies of new agents are screened to exclude patients with hepatitis. There are some data on the use of rituximab in HCV infection because it has been employed in the management of HCV-associated cryoglobulinemia, again with little evidence of untoward toxicity.18

Should HCV-Infected Patients Be Referred to a Subspecialist and Undergo Biopsy?

We believe that every patient who is found to be HCV infected should be evaluated by a hepatologist or gastroenterologist with experience in the diagnosis, treatment, and follow-up of patients with chronic hepatitis C. Referral is beneficial to these patients for several reasons. First, it provides the patients the opportunity to get detailed information regarding the nature of their disease, the factors that are associated with an adverse prognosis (alcohol use, obesity, other co-infections, etc.), the available treatment options, and their potential side effects. Second, referral could identify candidates for antiviral therapy that need additional diagnostic work-up, including determination of viral genotype, baseline and post-treatment serum viral loads, imaging of the liver (by ultrasound, CT, etc.), and possibly a baseline liver biopsy. Third, for patients with advanced liver disease (cirrhosis) who are not candidates for antiviral treatment, referral to a tertiary center for evaluation for liver transplantation may be necessary.

The role of liver biopsy in patients with chronic HCV infection is a matter of continuing debate among hepatologists and gastroenterologists.7 Liver biopsy provides valuable information that could significantly influence therapeutic decisions and determine the prognosis of chronically infected patients. Currently available guidelines propose antiviral treatment for HCV patients with abnormal alanine transaminase (ALT) values and histological findings showing chronic hepatitis and significant fibrosis (Ishak score greater than 3), in the absence of liver decompensation (ascites, hepatic encephalopathy, prolonged INR, etc.).7

Liver biopsy is particularly useful in patients with genotype-1 infection; for patients with genotypes -2 and -3 who usually demonstrate a good response to antiviral therapy (74% to 80%), antiviral treatment is recommended regardless of the liver biopsy results. Similarly, patients with persistently normal ALT values could benefit from antiviral therapy because 20% of them could have significant fibrosis in liver biopsy.7

Liver biopsy could also have a prognostic value for patients who are not considered candidates for immediate antiviral treatment (normal ALT values, low fibrosis score). In these cases, a repeat liver biopsy in four to five years could identify those that show progression of their liver disease that needs to be treated.

For patients with RA and chronic HCV infection, there is additional information that could be gained by a liver biopsy. For patients who are scheduled for DMARD therapy or for those already receiving DMARDs (such as methotrexate or leflunomide), therapeutic decisions could be greatly influenced by the liver biopsy results. In the case of significant liver fibrosis, starting or continuing therapy with potentially hepatotoxic DMARDs is not advisable. In such cases and in the absence of decompensated liver disease (ascites, encephalopathy, coagulopathy, or increased bilirubin), biologic therapy given as monotherapy should be seriously considered. If the liver biopsy shows minimal inflammation and little or no fibrosis, we believe that initiation or continuation of DMARD therapy, with or without the addition of biologics, under close monitoring of liver function and potentially repeating biopsy in a few years, is the preferred approach.

Can Interferon-Based Therapy for HCV Exacerbate RA and How Can I Manage the Risk?

There are no prospectively collected data on the incidence of arthritis exacerbation in patients with RA and HCV, receiving treatment with IFN-a–based regimens. It has been estimated that between 25% and 35% of patients with chronic hepatitis C receiving IFN-a develop arthralgias during treatment,19 but true inflammatory arthritis appearing either de novo or in patients with pre-existing articular disease is relatively rare. In an older study, Okanue et al found only two cases of RA in 677 patients with chronic hepatitis C treated with high doses of standard IFN-a.20 Nevertheless, well-documented cases of inflammatory arthritis developing in this setting have been reported in the literature.21-24

The decision to continue IFN-a therapy in such cases should be individualized. If the chance of achieving viral clearance with IFN-a therapy is considered high (patients with genotypes -2/3 or patients with genotype -1 and low pretreatment viral load and/or a favorable virological response after three months of therapy), every effort should be made to continue IFN-a therapy. In such cases, the use of adjunctive medications for RA like low dose prednisone (<10 mg/day) or even anti–TNF-a agents could be tried.

In cases where the possibility of viral clearance is low (patients with genotype-1 and high pretreatment viral load and/or absence of virologic response after three months of therapy) or where a severe exacerbation of arthritis not controlled with therapy is noted, we believe that IFN-a therapy should be stopped.

Conclusions

HCV is a common chronic viral infection that affects the diagnosis and management of RA in numerous ways. Rheumatologists should become knowledgeable about the clinical aspects of HCV infection, develop standards for screening, and establish close relationships with hepatologists skilled in assessing and managing patients with these complex disorders. Still, there are a number of questions that need to be answered concerning the long-term safety of biologic therapies in patients with chronic hepatitis C, as well as the antiviral and antirheumatic efficacy of combination therapies with antivirals and biologics in this group of patients. A number of trials are already in progress that will try to answer these questions, and certainly more are needed in the future.

Dr. Vassilopoulos is assistant professor of medicine–rheumatology at Athens University in Greece. Dr. Calabrese is professor of medicine at Cleveland Clinic Lerner College of Medicine of Case Western Reserve University and R.J. Fasenmyer Chair of clinical immunology and vice chair of the department of rheumatic and immunologic diseases at the Cleveland Clinic Foundation.

References

- O’Dell JR. Therapeutic strategies for rheumatoid arthritis. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:2591-2602.

- Scott DL, Kingsley GH. Tumor necrosis factor inhibitors for rheumatoid arthritis. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:704-712.

- Rustgi VK. The epidemiology of hepatitis C infection in the United States. J Gastroenterol. 2007;42:513-521.

- Parke FA, Reveille JD. Anti-tumor necrosis factor agents for rheumatoid arthritis in the setting of chronic hepatitis C infection. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;51:800-804.

- Groom H, Dieperink E, Nelson DB, et al. Outcomes of a Hepatitis C screening program at a large urban VA medical center. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2008;42:97-106.

- Lauer GM, Walker BD. Hepatitis C virus infection. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:41-52.

- Strader DB, Wright T, Thomas DL, Seeff LB. Diagnosis, management, and treatment of hepatitis C. Hepatology. 2004;39:1147-1171.

- Manning DS, Afdhal NH. Diagnosis and quantitation of fibrosis. Gastroenterology. 2008;134:1670-1681.

- Vassilopoulos D, Calabrese LH. Rheumatic manifestations of hepatitis C infection. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2003;5:200-204.

- American College of Rheumatology Subcommittee on Rheumatoid Arthritis Guidelines. Guidelines for the management of rheumatoid arthritis: 2002 Update. Arthritis Rheum. 2002;46:328-346.

- Mok MY, Ng WL, Yuen MF, Wong RW, Lau CS. Safety of disease modifying anti-rheumatic agents in rheumatoid arthritis patients with chronic viral hepatitis. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2000;18:363-368.

- Calabrese LH, Zein NN, Vassilopoulos D. Hepatitis B virus (HBV) reactivation with immunosuppressive therapy in rheumatic diseases: Assessment and preventive strategies. Ann Rheum Dis. 2006;65:983-989.

- Armstrong WS, Taege AJ. HIV screening for all: The new standard of care. Cleve Clin J Med. 2007;74:297-301.

- Saag KG, Teng GG, Patkar NM, et al. American College of Rheumatology 2008 recommendations for the use of nonbiologic and biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;59:762-784.

- Calabrese LH, Zein N, Vassilopoulos D. Safety of antitumour necrosis factor (anti-TNF) therapy in patients with chronic viral infections: Hepatitis C, hepatitis B, and HIV infection. Ann Rheum Dis. 2004;63 Suppl 2:ii18-ii24.

- Ferri C, Ferraccioli G, Ferrari D, et al. Safety of anti-TNF-alpha therapy in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and chronic HCV infection. J Rheumatol. 2008;35:1944-1949.

- Zein NN. Etanercept as an adjuvant to interferon and ribavirin in treatment-naive patients with chronic hepatitis C virus infection: A phase 2 randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. J Hepatol. 2005;42:315-322.

- Cacoub P, Delluc A, Saadoun D, Landau DA, Sene D. Anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody (rituximab) treatment for cryoglobulinemic vasculitis: Where do we stand? Ann Rheum Dis. 2008;67:283-287.

- Russo MW, Fried MW. Side effects of therapy for chronic hepatitis C. Gastroenterology. 2003;124:1711-1719.

- Okanoue T, Sakamoto S, Itoh Y, Minami M, Yasui K, Sakamoto M, et al. Side effects of high-dose interferon therapy for chronic hepatitis C. J Hepatol. 1996;25:283-291.

- Passos de Souza E, Evangelista Segundo PT, José FF, Lemaire D, Santiago M. Rheumatoid arthritis induced by alpha-interferon therapy. Clin Rheumatol. 2001;20:297-299.

- Pittau E, Bogliolo A, Tinti A, et al. Development of arthritis and hypothyroidism during alpha-interferon therapy for chronic hepatitis C. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 1997;15:415-419.

- Nadir F, Fagiuoli S, Wright HI, et al. Rheumatoid arthritis: A complication of interferon therapy. J Okla State Med Assoc. 1994;87:228-230.

- Chazerain P, Meyer O, Kahn MF. Rheumatoid arthritis-like disease after alpha-interferon therapy. Ann Intern Med. 1992;116:427.