Surgery

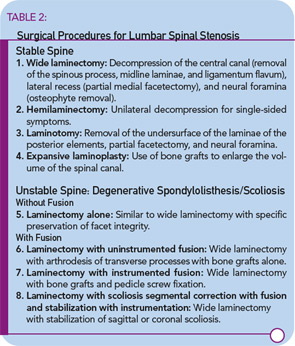

Surgical decompression is indicated in patients who have failed medical therapy and are physically incapacitated by spinal stenosis.16 I recommend surgical evaluation for patients who have leg pain with standing for 10 to 15 minutes or with walking short distances. Patients should understand that an operation relieves leg pain, not back pain. The age of the patient should not be the deciding factor in recommending surgery. Eighty- and ninety-year-old patients can benefit from decompression surgery if they are otherwise in good physical condition. A variety of surgical procedures is available for decompression of the lumbar spine. (See Table 2)

The goal of surgery is to obtain adequate decompression without causing instability. The difficulty for the spine surgeon is identifying the significant stenotic levels, because the degree of narrowing does not specifically identify the most symptomatic level. I rely on the experience of the surgeon to decide on the level and extent of decompression. Accomplishing this goal is more difficult in those with degenerative scoliosis or spondylolisthesis. The spinal surgeon determines the need for fusion and instrumentation after decompression. The surgical literature remains divided over the benefits of fusion with or without instrumentation as a part of a decompression procedure.

Therapeutic Outcomes

Very few studies have looked at the outcome of similar patients treated non-surgically or surgically over a similar time period.17 Investigators have described small groups of non-surgical spinal stenosis patients with stable symptoms for extended periods of time. Others have described a natural history of slow but steady decrease in function measured in years. Surgical decompression offers better short-term outcomes than medical therapy. Patients with fewer co-morbid conditions have better outcomes.18 However, the difference in benefit diminishes over time. Debate is ongoing on the fate of surrounding intervertebral disc spaces and the risk of re-stenosis.

Conclusions

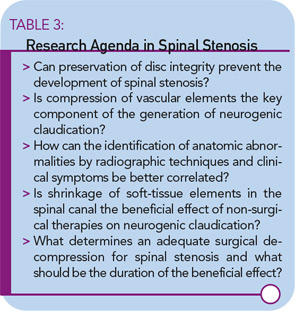

Lumbar spinal stenosis is an important medical disorder with an increasing effect on the aging population. Unfortunately, there have been few investigations into its pathogenesis, natural history, diagnostic criteria, and therapeutic options, resulting in a predicament of little evidence-based proof of diagnostic accuracy of tests or the clinical benefits of therapies. While unresolved issues should form the basis of an exciting research agenda (as shown in Table 3), clinicians cannot wait until this evidence is available to choose a therapy for their patients.

Clinical judgment is essential in achieving the best outcome for spinal stenosis patients. Our understanding of the illness suggests that initial non-surgical therapy is appropriate. Delayed surgery does not diminish the possibility of a favorable outcome, particularly in patients with good health and no cardiovascular co-morbidities. With the coming epidemic of spinal stenosis, therapeutic choices will become ever more frequent, challenging rheumatologists and other specialists treating this prevalent and debilitating condition.