Although lumbar spinal stenosis will have a major effect on public health, the number of studies on appropriate diagnostic and therapeutic choices is surprisingly small. Despite this lack of evidence-based options, clinicians need to make the best choices with available evidence and clinical acumen. In this article, I will provide my approach to this challenging clinical disorder based upon the available medical literature and my experience of 29 years in practice.

Definition and Pathogenesis

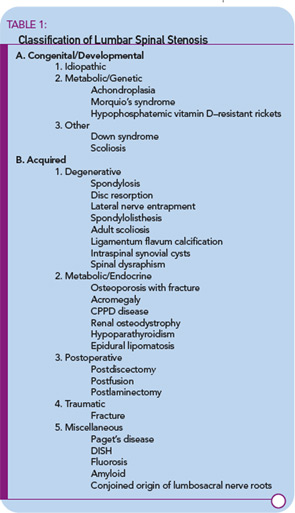

Spinal stenosis is a disorder characterized by insufficient room in the spinal canal for the neural elements. Most commonly, acquired degeneration of the anatomic structures of the lumbar spine results in narrowing of the central spinal canal, the lateral recesses, or the neural foramina. Acquired or secondary stenosis will be the focus of this article. Other major categories of spinal stenosis include other forms of acquired stenosis as well as congenital and developmental disorders.2 (See Table 1)

A basic understanding of the pathogenesis of this disorder is essential for making therapeutic decisions for the corresponding form of spinal stenosis. What might be appropriate for an intervertebral disc herniation (a form of acutely acquired spinal stenosis) will not necessarily be effective for spinal narrowing that has been decades in the making.

The earliest changes occur in the intervertebral discs that lose their structural integrity and start to flatten. The resulting biomechanical insufficiency results in transfer of stresses posteriorly to the ligaments and facet joints. The response to the added weight results in the development of osteophytes on facet joints and vertebral endplates, as well as the redundancy and thickening of the ligamentum flavum.3 Depending on a number of physical factors including the central anterioposterior diameter of the canal, trefoil canal shape, and the height of the neural foramina, stenosis may occur in different areas of the spinal canal with attendant clinical syndromes corresponding to the location of compression. For example, more severe central stenosis may cause urinary retention symptoms. Persistent radicular pain that is unrelieved with a change in position is more indicative of lateral recess stenosis.4

The mechanism of radicular pain production in spinal stenosis is incompletely understood. Individuals with similar degrees of canal narrowing experience different intensities and locations of pain. Mechanical compression of nerve roots may cause electrophysiological alterations in nerve conduction. However, slow, persistent compression is associated with neural adaptation that does not lead to symptoms. Simple compression of the neural elements alone does not fully explain the generation of radicular pain. Vascular compromise associated with arterial, capillary, and venous obstruction plays a substantial role in the development of neurogenic claudication.5 Standing in an extended posture decreases the room in the spinal canal while flexion increases the space.

The rapid reversibility of leg pain with a change in posture is strong evidence for the important role of vascular obstruction as a primary component of the pathogenesis of neurogenic claudication. The longer the duration of the vascular compromise, the more persistent and total becomes the neural dysfunction. The clinical correlate would be radicular pain followed by numbness and muscular weakness. Alleviation of vascular congestion can normalize the function of the sciatic nerve and diminish leg pain. Therefore, the goal of therapy is to maximize neural blood flow and restore nerve function.

Clinical History

Neurogenic or pseudoclaudication is the most common symptom associated with spinal stenosis.6 Pain that is associated with standing or walking occurs in the buttock, thigh, or lower leg. The patterns of back and/or leg pain are as different as the patients who have the disorder. Most patients will complain of low back and leg pain. A smaller proportion will have leg pain alone. Many patients will have bilateral leg pain. The extent of the leg pain may be different in the extremities. Multiple dermatomes may be affected. The widespread distribution of symptoms makes it difficult to ascribe compression to a single nerve root lesion. In addition to pain, patients may also have numbness, paresthesias, and weakness in the lower extremities. Less commonly, similar symptoms can occur while patients are lying down and are relieved by getting out of bed. Neurogenic claudication is relieved by lying down, sitting, or flexing at the waist. Many elderly patients enjoy going to the grocery store so that they can flex over the shopping carts.

Some of my most perplexing patients have been those with spinal stenosis. One was an executive with the chief complaint of medial knee pain. He wanted me to diagnose his problem so I could save his marriage. He had knee pain for about a year that was exacerbated by standing and relieved by sitting. He had been evaluated with knee radiographs and magnetic resonance (MR) demonstrating no abnormality. Knee braces and physical therapy were of no benefit. What did this have to do with his marriage? He could sit at his desk and play racquetball three times a week without pain, but could not dance more than a few minutes with his wife before he had to sit down. She suspected he did not love her anymore, but he did.

Of course, the problem was not in his knee, but in his lumbar spine. When the man played racquetball, he was in a flexed posture. When he danced, he was in an extended posture. An MR scan of the lumbar spine revealed his spinal stenosis. He received a course of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and epidural corticosteroid injections with an excellent response. His marriage was saved!

Other patients describe persistent leg pain that does not change significantly with assuming a flexed posture. They may not obtain relief by lying supine in bed. These are patients with compression associated with neural foraminal or lateral recess stenosis.

Physical Examination

Patients with spinal stenosis may have no physical abnormalities when examined in the seated position, and abnormalities may appear only after the patient is stressed by walking until leg pain appears.7 Sciatica caused by lumbar spinal stenosis is distinct from radiculopathy associated with an intervertebral disc herniation. Objective neurologic findings – including asymmetric reflexes, sensory loss, or motor weakness – are found in a minority of stenosis patients.8

In many circumstances, I complete the physical examination to be sure that no other findings indicate an alternate diagnosis. For example, an essential portion of the examination is internal and external rotation of the hips. On more than one occasion, I’ve diagnosed severe hip osteoarthritis in someone with leg pain with lumbar roentgenograms and MR scan demonstrating minimal narrowing with a presumptive diagnosis of lumbar spinal stenosis. I also palpate the feet for the presence of dorsalis pedis and posterior tibial pulses to eliminate the possibility of vascular claudication.

Radiographic Tests

Many radiographic techniques are available to evaluate the spinal stenosis patient.9 The least sensitive but most available is a set of plain roentgenograms of the lumbar spine. I order anteroposterior and lateral views as my initial test in most individuals. I may order oblique views if I am concerned about facet joint osteophytes and foraminal stenosis. I obtain flexion and extension views to observe abnormal motion if I am concerned about instability of the spine. This method is helpful in identifying potential candidates with significant lumbar spondylosis, foraminal narrowing, short pedicles, facet joint arthritis, or degenerative spondylolisthesis. Remember that these features are common findings among asymptomatic individuals of a similar age. Roentgenographic abnormalities are compatible, but not diagnostic, of spinal stenosis.

MR is the next radiographic test I order when further delineation of the osseous and soft tissue elements in both the sagittal and axial planes of the lumbar spine is necessary. This technique can visualize the areas of neural compression in the central canal, the lateral recess, and the neural foramen without X-ray exposure. I look for abnormalities at levels of the lumbar spine that correlate with the patient’s clinical symptoms. However, it is rare that just one level of the lumbar spine is stenotic with only mild spondylosis at other levels. Not uncommonly, more than one level has some degree of stenosis with the greatest narrowing on the opposite side to the one that is most symptomatic. MR abnormalities are compatible with, but not diagnostic of, spinal stenosis. (See Figure 1)

MR techniques are constantly advancing. For example, there are now MR scanners that allow subjects to stand during the examination. One of the reasons that an inexact correlation exists between MR findings and clinical symptoms may be the supine position of patients in the MR tube, because the lying position minimizes canal narrowing. Recreating the most symptomatic position for the MR evaluation may maximize the anatomic abnormalities that cause compression. I predict that studies in the upright position will become the preferred diagnostic method for spinal stenosis as the technology improves and the scanners are readily available.

Computed tomography (CT) is an excellent technique to identify the osseous structures crowding the spinal canal. Myelographic dye enhances the resolution. I rarely order CT myelograms because I see this type of evaluation as a pre-operative test and expect the spinal surgeon to order one once a decision involving decompression surgery has been made.

Electrodiagnostic Tests

Electromyography (EMG) and nerve conduction tests (NCTs) are not routinely used to evaluate spinal stenosis. EMG and NCTs are abnormal in a proportion of spinal stenosis patients with persistent radicular symptoms, and the most common finding is bilateral multilevel radiculopathy. EMG cannot consistently predict the specific level of nerve compression associated with leg pain. EMG’s greater utility lies in determining the presence or absence of peripheral neuropathy and peripheral nerve entrapment syndromes that may be present simultaneously in an elderly population. It is in this circumstance that I utilize these tests. Somatosensory potentials may have sensitivity to identify levels of nerve root compression, however, they may be affected by processes that affect the peripheral nerves, nerve roots, dorsal columns of the spinal cord, and brain. Abnormalities are not specific for spinal canal lesions.

Differential Diagnosis

A recent systematic review examined the accuracy of diagnostic tests for lumbar spinal stenosis.10 The review of 41 studies concluded that no clinical, radiographic, or interventional injection method was the “gold standard” for the diagnosis of spinal stenosis.

With few evidence-based studies to identify definitive tests for its diagnosis, lumbar spinal stenosis remains a clinical diagnosis characterized by specific historical and physical findings and confirmed, but not diagnosed, by radiographic techniques documenting compression of neural elements.

Leg pain is caused by a number of ailments in the elderly. Vascular claudication is manifested by leg pain associated with physical activity that radiates from the foot or calf, proximally. Vascular insufficiency causing lower leg pain associated with riding a bicycle is a helpful finding in differentiating between the two forms of claudication. Hip arthritis will cause pain with walking but rarely below the knee. Peripheral neuropathy will cause lower leg dysesthesias that are prominent at night when the individual is supine.

Facet joint syndrome may cause symptoms that mimic lumbar spinal stenosis. These patients have back pain with extension of the spine. Pain in the buttock and posterior thigh may develop with prolonged compression associated with standing. Patients may walk in the flexed posture for extended distances without pain. Facet syndrome is unassociated with any neurologic abnormalities.

Management

Lumbar spinal stenosis management requires judgment that matches the severity of functional impairment with benefits and risks of the interventions.11 The options range from education, to weight loss, to exercises, to drugs, to injections, to surgical decompression. No one therapy works for all patients. Some therapies are not worth the risks. Other patients have no choice but surgical decompression if genitourinary or gastrointestinal dysfunction is imminent.

When advising the elderly spinal stenosis patient, I try to gauge the impact of their functional impairment in standing and walking with their general medical condition. I tell my patients, “You are only as young as your oldest part.” For example, most patients have co-morbidities, including cardiovascular disease, pulmonary insufficiency, and diabetes. In many of these individuals, spinal stenosis does not limit their function. Instead, they are limited because of angina after walking two blocks, or dyspnea after three blocks. These individuals have cardiovascular or pulmonary disease that limits activity before leg pain causes them to take a seat. The non-musculoskeletal systems are their oldest parts. In these patients, I attempt to relieve pain with the simplest of therapies. In other patients, spinal stenosis is their only major health problem. These individuals are treated intensively to reverse neurogenic claudication. In these individuals, the spine is their oldest part.

Non-surgical

The recommendations I make for patients with spinal stenosis are based upon the few outcomes trials that are in the literature and the knowledge of the pathogenesis of the disease. Space-occupying tissues compress the neural elements when the volume in the canal is diminished. The goal of therapy is to maximize the space in the canal by flexing the spine and reversing swelling of any inflamed soft tissues.

I recommend the following for initial therapy:

1 The patient should make an effort to achieve an ideal body weight. Weight loss places less strain on the spine and decreases the effort needed to walk any distance.

2 Riding a stationary bicycle is a way to obtain aerobic exercise and increase calorie utilization without stressing the lumbar spine.

3 Water exercises with or without flotation devices are an alternative for those individuals who have difficulty walking short distances.

4 Abdominal strengthening exercises allow a patient to place their spine in a pelvic tilt, maximizing volume in the canal. Strengthening buttock and thigh muscles is also beneficial. Physical therapy programs that include these exercises have documented improved function.12

5 Smoking cessation is important. Lowering levels of bloodstream carbon monoxide can only be helpful to nerve roots starved for oxygen.

6 Education is key. Information empowers patients to be active in their own care. Understanding the purpose of therapy gets patients to participate to a greater degree.13

Drug therapies are effective in improving physical function and decreasing pain.11,14 I prefer anti-inflammatory drugs over pure analgesics for the initial therapy of spinal stenosis. The theoretical ability of NSAIDs to decrease soft tissue swelling specifically addresses the goal of therapy to maximize the volume in the spinal canal. No NSAID is more effective than another for spinal stenosis. In elderly patients, use the smallest effective dose. The toxicities of NSAIDs (gastrointestinal ulcers, hypertension, and peripheral edema, among others) are greater risks for an elderly population. I offer concomitant medications to reduce side effects in susceptible patients.

Consider opioid analgesics for patients with severe, incapacitating pain who are not good candidates for NSAID therapy, or who have found non-narcotic analgesics to be ineffective. Short-acting opioids can be used when patients are planning an activity that may cause radicular pain. I recommend taking the analgesic prior to the physical activity. I limit the use of long-acting opioids to individuals with persistent pain who are poor surgical candidates.

I utilize low-dose corticosteroid (5 mg to 10 mg QD) in patients who have difficulties with NSAIDs and opioids. No clinical trials have shown the benefits of steroids for spinal stenosis, but my clinical experience has included a group of patients taking low-dose steroids who are able to function with decreased leg pain. Theoretically, the anti-inflammatory effects of steroids may decrease swelling in the spinal canal. I also use steroids in patients who have a good response to epidural corticosteroid injections but are unable to receive additional injections.

I recommend epidural corticosteroid injections to patients with only partial benefit from exercise and NSAID therapy.15 Epidural injections are usually given in a series of three. Injections for herniated discs are given over a six-week period to alter acutely swollen tissues. I order epidurals at a different interval for spinal stenosis because of the different pathology. Injections are limited to three over a six-month period, so I order injections every two months or later and delay subsequent injections until symptoms recur. I have patients who have repeated epidural injections for years without needing surgical decompression.

Surgery

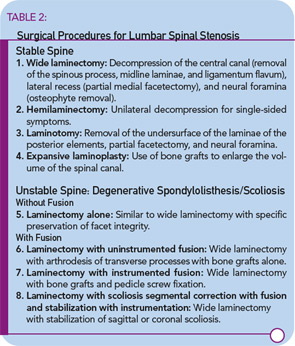

Surgical decompression is indicated in patients who have failed medical therapy and are physically incapacitated by spinal stenosis.16 I recommend surgical evaluation for patients who have leg pain with standing for 10 to 15 minutes or with walking short distances. Patients should understand that an operation relieves leg pain, not back pain. The age of the patient should not be the deciding factor in recommending surgery. Eighty- and ninety-year-old patients can benefit from decompression surgery if they are otherwise in good physical condition. A variety of surgical procedures is available for decompression of the lumbar spine. (See Table 2)

The goal of surgery is to obtain adequate decompression without causing instability. The difficulty for the spine surgeon is identifying the significant stenotic levels, because the degree of narrowing does not specifically identify the most symptomatic level. I rely on the experience of the surgeon to decide on the level and extent of decompression. Accomplishing this goal is more difficult in those with degenerative scoliosis or spondylolisthesis. The spinal surgeon determines the need for fusion and instrumentation after decompression. The surgical literature remains divided over the benefits of fusion with or without instrumentation as a part of a decompression procedure.

Therapeutic Outcomes

Very few studies have looked at the outcome of similar patients treated non-surgically or surgically over a similar time period.17 Investigators have described small groups of non-surgical spinal stenosis patients with stable symptoms for extended periods of time. Others have described a natural history of slow but steady decrease in function measured in years. Surgical decompression offers better short-term outcomes than medical therapy. Patients with fewer co-morbid conditions have better outcomes.18 However, the difference in benefit diminishes over time. Debate is ongoing on the fate of surrounding intervertebral disc spaces and the risk of re-stenosis.

Conclusions

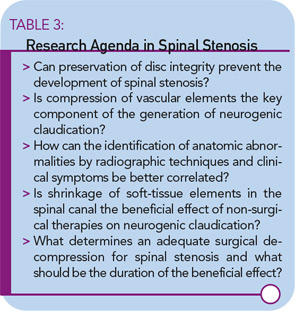

Lumbar spinal stenosis is an important medical disorder with an increasing effect on the aging population. Unfortunately, there have been few investigations into its pathogenesis, natural history, diagnostic criteria, and therapeutic options, resulting in a predicament of little evidence-based proof of diagnostic accuracy of tests or the clinical benefits of therapies. While unresolved issues should form the basis of an exciting research agenda (as shown in Table 3), clinicians cannot wait until this evidence is available to choose a therapy for their patients.

Clinical judgment is essential in achieving the best outcome for spinal stenosis patients. Our understanding of the illness suggests that initial non-surgical therapy is appropriate. Delayed surgery does not diminish the possibility of a favorable outcome, particularly in patients with good health and no cardiovascular co-morbidities. With the coming epidemic of spinal stenosis, therapeutic choices will become ever more frequent, challenging rheumatologists and other specialists treating this prevalent and debilitating condition.

Dr. Borenstein is a rheumatologist with Arthritis and Rheumatism Associates in Washington, D.C., and a TR editorial board member.

References

- Boden SD, David DO, Dina TS, et al. Abnormal magnetic-resonance scans of the lumbar spine in asymptomatic subjects. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1990;72A:403-408.

- Moreland LW, Lopez-Mendez A, Alarcon GS. Spinal stenosis: A comprehensive review of the literature. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 1989;127-149.

- Butler D, Trafinow JH, Andersson GBJ, et al. Discs degenerate before facets. Spine. 1990;15:111-113.

- Porter RW. Spinal stensosis and neurogenic claudication. Spine. 1996;21:2046-2052.

- Akuthota V, Lento P, Sowa G. Pathogenesis of lumbar spinal stenosis pain: Why does an asymptomatic stenotic patient flare? Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am. 2003;14:17-28.

- Hall S, Bartleson JD, Onofrio BM, et al. Lumbar spinal stenosis. Ann Intern Med. 1985;103:271-275.

- Jonsson B, Stromqvist B. Symptoms and signs in degeneration of the lumbar spine. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1993;75B:381-385.

- Katz JN, Dalgas M, Stucki G, et al. Degenerative lumbar spinal stenosis. Diagnostic value of the history and physical examination. Arthritis Rheum. 1995;38:1236-1241.

- Richmond BJ, Ghodadra T. Imaging of spinal stenosis. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am. 2003:14:41-56.

- De Graaf I, Prak A, Bierma-Zeinstra S, et al. Diagnosis of lumbar spinal stenosis: A systematic review of the accuracy of diagnostic test. Spine. 2006;31:1168-1176.

- Atlas SJ, Delitto A. Spinal stenosis: Surgical versus nonsurgical treatment. Clin Orthop Rel Res. 2006;443:198-207.

- Whitman JM, Flynn TW, Childs JD, et al. A comparison between two physical therapy treatment programs for patients with lumbar spinal stenosis. Spine. 2006;31:254-259.

- Borenstein D. ACR Patient Fact Sheet. Back Pain. Available online at www.rheumatology.org/public/factsheets/backpain_new.asp?aud=pat. Last accessed July 3, 2007.

- Simotas AC, Dorey FJ, Hansraj KK, Cammisa F Jr. Nonoperative treatment for lumbar spinal stenosis. Spine. 2000;25:197-203.

- Botwin KP, Gruber RD. Lumbar epidural steroid injections in the patient with lumbar spinal stenosis. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am. 2003;14;121-141.

- Sengupta DK, Herkowitz HN. Lumbar spinal stenosis. Treatment strategies and indications for surgery. Orthop Clin North Am. 2003;34:281-295.

- Atlas SJ, Keller RB, Wu YA, Deyo RA, Singer DE. Long-term outcomes of surgical and nonsurgical management of lumbar spinal stenosis. Spine. 2005;30:936-943.

- Airaksinen O, Herno A, Turunen V, et al. Surgical outcome of 438 patients treated surgically for lumbar spinal stenosis. Spine. 1997;22:227-228.