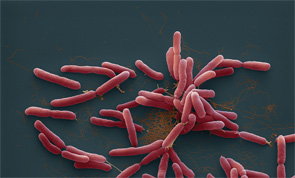

Burkholderia pseudomallei bacteria on a color-enhanced scanning electron micrograph (SEM). Image Credit: Eye of Science / Science Source

Burkholderia pseudomallei, the causative agent of melioidosis, is endemic in Southeast Asia and northern Australia.1 In recent years, the incidence of melioidosis has increased worldwide. Septic arthritis is a rare, but well-recognized, manifestation of melioidosis.

Case Report

A 49-year-old woman with known diabetes was admitted elsewhere with uncontrolled diabetes and fever. She was found to be in diabetic ketoacidosis. During her hospital stay, she had acute onset of severe pain, swelling and redness over the right shoulder joint. The shoulder joint was surgically drained, empiric parenteral antibiotics were initiated, and the patient was transferred to our hospital for further management.

On examination, she was febrile, the right shoulder was tender and warm, and all range of movement was severely restricted. There was also erythematous swelling of the right second proximal interphalangeal (PIP) joint, and diffuse swelling and tenderness over the left calf area.

Laboratory results included the following: hemoglobin, 9.8 gm/dL; leukocyte count, 13,400 cu/mm3 (90% neutrophils); platelet count, 4.36 cu/mm3; ESR, 106 mm/hr; CRP, 96 mg/dL; SGPT, 48 IU/L; creatinine, 0.8 mg/dL; rheumatoid factor and anti-CCP antibody were both negative. Lower limb color Doppler ultrasonography showed a lower left limb intramuscular fluid collection suggestive of an abscess.

An MRI of the right shoulder showed multiple abscesses with osteomyelitic changes (see Figures 1 and 2).

The synovial fluid culture from the shoulder, from the referring hospital, showed gram-negative bacilli on smear, but the organism was not identified. She was switched to injectable cefipime and tazobactam.

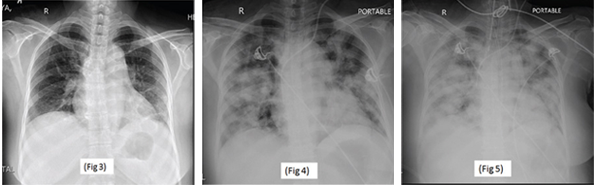

She underwent incision and drainage of the right shoulder joint and the left leg abscess. On the third postoperative day, she developed acute-onset tachypnea, and a chest X-ray showed changes of acute respiratory distress syndrome (see Figures 3, 4 and 5). The patient was intubated and treated with parenteral meropenem. However, she became anuric and succumbed to hyperkalemia-induced arrhythmia and cardiac arrest.

The day after her death, bacterial culture reports confirmed the growth of Burkholderia pseudomallei (B. pseudomallei) from the synovial fluid.

(click for larger image) MRIs of the right shoulder showing a collection within the right axilla (Fig. 1, top) and hyperintense signals from the head of the right humerus (Fig. 2).

Discussion

Melioidosis, also known as pseudoglanders or Whitmore’s disease, is caused by a gram-negative bacillus previously classified under genus pseudomonas—B. pseudomallei. It was identified in Burma in 1911 by Whitmore and Krishnaswami. It is classically characterized by the development of pneumonia and multiple abscesses, with a mortality rate as high as 40%. Melioidosis is an important cause of community-acquired sepsis in Southeast Asia and Australia and is classified as a Group B bioterrorism agent.1,2

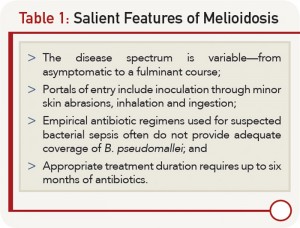

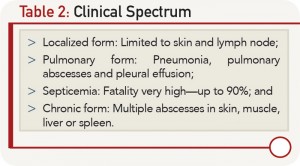

The disease spectrum is variable, and the infected individual can remain a carrier with totally asymptomatic infection or remain latent for years and manifest whenever cell-mediated immunity is suppressed. Melioidosis is known to present as a febrile illness, ranging from an acute fulminant septicemia to a chronic, debilitating localized infection and abscess formation (see Table 1, and Table 2).

The common portals of entry of B. pseudomallei are inoculation through minor skin abrasions, inhalation and ingestion. The normal incubation period in cases of melioidosis ranges from 1–21 days (mean nine days). The longest recorded apparent incubation period is 61 years.

Septic arthritis and osteomyelitis are rare, but well-recognized, forms of the disease.3,4 Generally, septic arthritis arises from the hematogenous dissemination of the organism, but it may follow direct spread from other organs or soft tissue infections over joints. Large joints, such as the knee, ankle, elbow or shoulder, are usually involved in this disease. The most commonly affected joints are the knee and shoulder.4 Melioidotic septic arthritis is often seen in patients with chronic diseases, including diabetes mellitus, chronic renal failure, cirrhosis, systemic lupus erythematosus and malignancies.3,4 Kosuwon et al found that diabetes mellitus was a predisposing factor in the majority of patients with septic arthritis.4

Serial chest X-rays: on the day of admission (Fig. 3), on the third postoperative day (Fig. 4) and on the fourth postoperative day (Fig. 5).

A delay in diagnosis can be fatal, because empirical antibiotic regimens used for suspected bacterial sepsis often do not provide coverage of B. pseudomallei. A culture of B. pseudomallei from any clinical sample is a sine qua non for diagnosis of melioidosis. Gram stain of synovial fluids is a quick approach, but the identification of gram-negative bacilli with bipolar staining is infrequent. Latex agglutination test based on polyclonal or specific monoclonal antibodies to lipopolysaccharide or exopolysaccharide can, therefore, be undertaken for definitive identification.2 Serological tests,

such as enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, to detect immunoglobulin M and immunoglobulin G antibodies, and molecular methods (e.g., polymerase chain reaction) are also used for definitive diagnosis of disease.1,2

B. pseudomallei is inherently resistant to ampicillin, penicillin, first- and second-generation cephalosporins, gentamycin, tobramycin, streptomycin and polymyxin.1,2 Treatment consists of two phases:

- Intensive phase consisting of 10–14 days’ treatment with ceftazidime, imipenem or meropenem given parenterally.

- Oral eradication phase with three to six months of trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole.1,2

Even with optimal treatment, the mortality from acute severe melioidosis is high (30–47%), as in our case.

G.C. Yathish, MD, is a second-year rheumatology DNB student at Hinduja Hospital in Mumbai, India.

Taral Parikh, MD, is a third-year rheumatology DNB student at Hinduja Hospital in Mumbai, India.

Parikshit Sagdeo, MD, is a first-year rheumatology DNB student at Hinduja Hospital in Mumbai, India.

Balakrishnan Canchi, MD, is the chief of rheumatology at Hinduja Hospital in Mumbai, India.

Gurmeet Mangat, MD, is a consultant rheumatologist at Hinduja Hospital in Mumbai, India.

Why Rheumatologists Need to Know about Melioidosis

- It’s common in an immunocompromised host, so many of our patients are at risk;

- It can present as septic arthritis;

- The number of cases appears to be increasing in Southeast Asia and Africa;

- A handful of cases are reported yearly in the U.S., mainly among travelers and immigrants; and

- B. pseudomallei is considered a Group B bioterrorism agent.

References

- Raja NS, Ahmed MZ, Singh NN. Melioidosis: An emerging infectious disease. J Postgrad Med. 2005 Apr–Jun;51(2):140–145.

- White NJ. Melioidosis. Lancet. 2003 May 17;361(9370):1715–1722.

- Currie BJ, Fisher DA, Howard DM, et al. Endemic melioidosis in tropical northern Australia: A 10-year prospective study and review of the literature. Clin Infect Dis. 2000 Oct;31(4):981–986.

- Kosuwon W, Taimglang T, Sirichativapee W, et al. Melioidotic septic arthritis and its risk factors. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2003 Jun;85-A(6):1058–1061.

- Jesudason MV, Anbarasu A, John TJ. Septicaemic melioidosis in a tertiary care hospital in south India. Indian J Med Res. 2003 Mar;117:119–121.

- Hoque SN, Minassian M, Clipstone S, et al. Melioidosis presenting as septic arthritis in Bengali men in east London. Rheumatology (Oxford). 1999;38(10):1029–1031.