The relative inaccessibility of the intraocular compartments (i.e., anterior chamber and vitreous cavity) poses an obvious limitation to performing an extensive diagnostic work-up, as does the minute volumes of fluid that are available even if a diagnostic paracentesis is performed. Even the most advanced centers offer only a handful of microbiologic assays for intraocular fluid including culture (e.g., bacterial, acid fast bacilli, fungal and rarely viral) and pathogen-specific polymerase chain reactions (e.g., herpes simplex virus types 1 and 2, varicella zoster virus, cytomegalovirus, Toxoplasma gondii).

Not surprisingly, an etiologic agent is not identified in more than half of uveitis cases, and physicians are forced to make empiric treatment decisions. If local or systemic immunosuppression is pursued to treat a presumed autoimmune cause of uveitis, this can serve to exacerbate an undiagnosed intraocular infection.

We first used MDS in three uveitis cases in which a pathogen had already been identified and showed that MDS was consistent with the gold standard microbiologic testing for herpes-simplex virus type 1, Cryptococcus neoformans and Toxoplasma gondii.1

We also showed that in two noninfectious intraocular fluid samples, MDS did not detect any pathogenic organisms. Rather, the MDS results from these two samples largely reflected organisms that are found in laboratory reagents.

Case Study

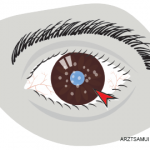

After showing that MDS could be used to identify common infectious causes of uveitis, we turned to a patient with a 16-year course of chronic, idiopathic, asynchronous bilateral uveitis. In 1999, he noticed floaters and mild decreased vision in the left eye. The patient was seen by an ophthalmologist in Germany and found to have anterior uveitis, which is the most common uveitis entity.

A routine laboratory work-up (e.g., HLA-B27, RF, c-ANCA, hepatitis serology panel and PPD) was unrevealing. The patient’s intraocular inflammation was managed with topical steroids and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) with minimal improvement.

Two years later, the patient had ocular symptoms in the right eye and was diagnosed with bilateral idiopathic anterior uveitis. RPR and repeat HLA-B27 were negative. At this time, he had already had cataract surgery in the left eye, likely due to a combination of topical steroid and uncontrolled intraocular inflammation. Seven years after disease onset, the patient was initiated on a potent topical steroid (Durezol or difluprednate). That failed to control his inflammation, so he was placed on systemic prednisone and methotrexate, in addition to frequent topical steroid drops.