He eventually developed a white cataract in the right eye and underwent cataract surgery and IOL placement. His immunosuppression was discontinued after one year due to treatment futility. There was a discussion to transition the patient to another antimetabolite, CellCept, but he never started the medication due to recurrent lower extremity rashes.

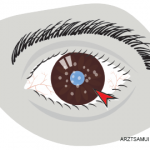

The patient relocated to San Francisco in 2012 and sought care at the Proctor Foundation at the University of California, San Francisco. His exam was notable for inflammatory cells in the anterior and vitreous cavity bilaterally. Further, he had heterochromia (different iris color between the two eyes) suggestive of chronic viral infection.

An anterior chamber paracentesis was performed, and aqueous fluid was tested for HSV, VZV and CMV by polymerase chain reaction (PCR). Although the results were negative for herpesvirus infection, the patient was maintained on systemic and intravitreal antivirals because of the high degree of clinical suspicion. When he had to undergo a pars plana vitrectomy to remove an epiretinal membrane in the left eye, another diagnostic work-up was initiated, which included cytology, bacterial and fungal cultures, HSV, VZV and CMV PCRs. Again, all tests were nondiagnostic.

The patient’s aqueous fluid was finally evaluated by unbiased MDS. After filtering out host sequencing reads and environmental reads, the most predominant remaining viral reads aligned to rubella virus, a known infectious cause of uveitis. More importantly, a near full-length genome (99.3%) of the rubella virus was obtained. Phylogenetic analysis revealed that the rubella virus detected in the patient’s eye was mostly closely related to a rubella virus isolated in Stuttgart, Germany, in 1992.

Upon further questioning, the patient reported that he had had a three-day fever and whole body rash in 1993 when he was living in Germany. Because of the German vaccination policies at the time, he had not been immunized against rubella virus. Thus, it appears as if his ocular history actually began in 1993, a full six years prior to the onset of his uveitis.

In this case, MDS not only identified a very unusual cause of infectious uveitis, it also highlighted the Achilles heel of pattern recognition as a primary means of diagnosis in patients with inflammatory disease. In the vast majority of cases, a patient’s three-day fever and rash that had occurred six years prior to the onset of their current clinical syndrome would not be considered clinically relevant—or even asked about by most clinicians. Thus, MDS has the ability to not only identify unusual pathogens, but it will also help redefine clinical syndromes by its unbiased and comprehensive approach.