Results from multiple investigations have pieced together a picture of rheumatoid arthritis (RA) as a multifactorial disease that occurs in sequential phases. Certain alleles with the major histocompatibility (MHC) class II locus, specifically DRB1, confer a higher risk for disease. Despite risk factors such as this, individuals with genetic susceptibility to RA may remain healthy for a lifetime.

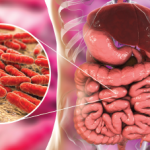

A great deal of research has explored environmental factors contributing to the pathogenesis of RA. This research has included studies of the human microbiome—a diverse set of microorganisms living primarily in the human gut. While gut microbiota have been implicated in animal models of arthritis, the verdict is still out on the role of dysbiosis and human RA.

A new study suggests that intestinal expansion of Prevotella copri may be associated with the pathogenesis of RA. Jose U. Scher, MD, director of the Arthritis Clinic at New York University Hospital for Joint Diseases in New York City, and colleagues describe the results from their stool-sample analysis in eLIFE.1 The team compared the genome sequence of gut bacteria from patients with RA to those from healthy controls.

“Despite impressive advances in RA pathogenesis, diagnostics, and therapeutics, the etiology of this disease remains elusive. For many decades, gut bacteria have been implicated in inflammatory arthritis. Using novel technologies that help bypass the need for classic cultures, we have been able to describe an association of a particular species P. copri with an autoimmune phenotype,” says Dr. Scher.

In particular, new-onset untreated RA is strongly correlated with the presence of P. copri. The prevalence of a Prevotella-dominated metagenome is also associated with a significant decrease in purine metabolic pathways.

Colonization of mice with P. copri confirm the ability of P. copri to dominate colonic commensal micobiota in the absence of obvious disease. Mice colonized with P. copri did, however, display increased inflammation during dextran sodium sulfate (DSS)–induced colitis.

Dr. Scher expressed his surprise with two findings, “First, that P. copri abundance in the gut correlates inversely with presence of shared epitope alleles. This may represent a gene–environment [microbiome] interaction that needs further investigation.”

He also was surprised by the implication that the microbiome may explain how certain immunosuppressants are metabolized.

He proposed that gut microbial composition may partially explain why some patients respond better to methotrexate than others.

The difference in response may be due to the ability of the gut microbiome to modulate drug bioavailability.