Alila Medical Media / shutterstock.com

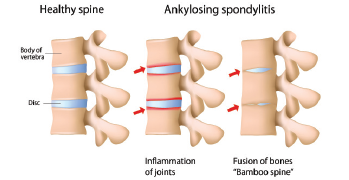

What factors drive inflammation and progressive disease in ankylosing spondylitis (AS)? The answers have long eluded rheumatologists. Although 90% of patients with AS test positive for the HLA-B27 gene, pieces remain missing in our understanding of this chronic, inflammatory disease, which often leads to pain, spinal fusion and, in about half of patients, gut involvement, such as a bowel disorder.1,2

Past research has identified cells that drive inflammation and new bone formation in spondyloarthritis (SpA) studies in mice, but not in humans, says Nigil Haroon, MD, PhD, Krembil Research Institute, University of Toronto in Ontario, Canada.3

“The difficulty in assessing tissue is a major factor affecting our ability to study the pathogenesis of AS. Back pain is a common symptom seen in the general population, but only a small portion of these patients have AS as the cause of their pain,” he says. “There is an average delay of eight years from symptom onset to AS diagnosis, so we have limited ability to study the preclinical and early stages of the disease. Animal models available for SpA [don’t provide] a perfect representation of human disease.”

In a new paper in the September issue of Arthritis & Rheumatology, Dr. Haroon and his colleagues reveal the likely culprit: macrophage migration inhibitory factor (MIF).4 According to their study, “Macrophage Migration Inhibitory Factor Induces Inflammation and Predicts Spinal Progression in Ankylosing Spondylitis,” this potent cytokine drives the two major disease processes in AS and could be both a new target for drug development and a potential biomarker to identify AS patients with more aggressive disease, says Dr. Haroon.

“If proved in preclinical trials, MIF would be an ideal therapeutic target [for] clinical trials in AS,” he says. “MIF appears to be an independent predictor of spinal fusion, and in vitro and in vivo, it can directly drive osteoblast activation and mineralization.”

Gut–Spine Connections

The study aimed to learn more about AS disease progression and a long-suspected gut–joint link, says Dr. Haroon. “[We have] several clues to this link. Just to name a few, 10% of AS patients have clinical inflammatory bowel disease, [but] 60–70% have microscopic colitis. Mucosa-associated invariant T cells [MAIT cells] and other gut-derived cells have been implicated in arthritis,” he says, adding that MIF also plays a key role in the development of chronic colitis in mice.5 MIF, which helps regulate innate immunity, may also play a role in other inflammatory autoimmune diseases, as well as sepsis.6

In studies of mice with the HLA-B27 gene, researchers saw the usual clinical signs of AS, but if the mice “are housed in a germ-free condition, no clinical manifestations develop. So an environmental trigger for the development of spondyloarthritis is likely, with the gut being a prime source,” says Dr. Haroon.

Intestinal bugs, such as Heliobacter pylori, have been shown to trigger MIF release in past studies, so the researchers suspected “the gut could be where the disease process begins in SpA,” says Dr. Haroon.7 “A gut-related factor could be a clue to onset, severity or certain clinical features of the disease. Fecal and serum calprotectin levels have been used for predicting irritable bowel syndrome presence and activity, but a similar marker for AS has yet to be conclusively proved.”

The Study

The researchers enrolled 147 AS patients who satisfied the modified New York diagnostic criteria and 61 healthy volunteers used as controls.8 They collected baseline serum samples, annually recorded clinical variables and took radiographs every two years. The AS patients were classified as either progressors or nonprogressors based on the annual rate of increase in their modified Stoke AS Spinal Score (mSASSS), with 56 progressors and 91 nonprogressors. The AS patients stayed on their regular, daily doses of standard therapy: non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and/or tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitors.

The researchers also analyzed the patients’ ileal tissue to identify MIF-producing cells in the gut. Using flow cytometry, they identified MIF-producing subsets, expression patterns of the MIF receptor CD74, and MIF-induced TNF production in the patients’ peripheral blood samples. They analyzed MIF-induced mineralization of osteoblast cells, and measured β-catenin levels.

The study’s results show MIF plays important roles in AS disease progression. In the AS patients, MIF serum levels measured higher at baseline compared with levels in healthy controls. This factor independently predicted radiographic disease progression in these patients, says Dr. Haroon.

MIF levels measured higher in their synovial fluid, and MIF expression was elevated in their peripheral joints and ileum tissue, as well. MIF-producing macrophages and Paneth cells were enriched in their guts. MIF also induced TNF production in the AS patients’ monocytes. MIF activated β-catenin in their osteoblasts and promoted osteoblast mineralization, which suggests it possibly stimulates the pathogenic bone growth seen in AS.

AS patients in the study also featured lower levels of the protein CD74 in their monocytes, which could be a sign of disease progression that must be explored further, says Dr. Haroon. CD74 is a high-affinity receptor for MIF. When MIF binds to CD74’s surface, its intracellular domain (ICD) cleaves or splits open.

“The ICD can mediate the pro-inflammatory effects of MIF,” Dr. Haroon says. “The antibody cannot recognize the cleaved, intracellular CD74. So, that decrease in intracellular CD74 indicates active signaling of the MIF-CD74 axis in AS patients’ monocytes.”

Although AS patients in the progressor group tended to be smokers, smoking didn’t stand out as a factor in this analysis. NSAID use also didn’t appear to affect disease progression.

We Need Better Therapies

Rheumatologists have few options to manage AS symptoms and disease progression, says Dr. Haroon. First-line therapy is an NSAID to control inflammation and pain, followed by TNF inhibitors if a patient does not respond.9

“For [AS] treatment, we have been extrapolating drugs used in [rheumatoid arthritis (RA)]. NSAIDs help only a small proportion of patients with AS. Disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs [that are] helpful in RA have no efficacy in axial disease,” he says. “TNF inhibitors and IL-17 inhibitors control disease symptoms in only 50–60% of patients. There are no good prognostic algorithms for predicting treatment response in AS.”

MIF could be a promising target for the development of a new, more effective therapy for these patients and a way to better identify patients at risk for rapid disease progression, he says.

“MIF is the first innate immune cytokine … shown to drive both disease processes directly,” Dr. Haroon says. “MIF appears to be upstream of both TNF and Th17 cytokines. MIF may not only be a good target for treatment, it may also be a good biomarker to identify AS patients who have a particularly aggressive disease course. These patients could be selected for close follow-up and aggressive treatment, and enrolled in targeted therapeutic trials.”

Susan Bernstein is a freelance journalist based in Atlanta.

References

- Tam LS, Gu J, Yu D. Pathogenesis of ankylosing spondylitis. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2010 Jul;6(7):399–405.

- Rudwaleit M, Baeten D. Ankylosing spondylitis and bowel disease. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2006 Jun;20(3):451–471.

- Sherlock JP, Joyce-Shaikh B, Turner SP, et al. IL-23 induces spondyloarthropathy by acting on RORγt+ CD3+ CD4-CD8- entheseal resident T cells. Nat Med. 2012 Jul 1;18(7):1069–1076.

- Ranganathan V, Ciccia F, Zeng F, et al. Macrophage migration inhibitory factor induces inflammation and predicts spinal progress in ankylosing spondylitis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2017 Sep;69(9):1796–1806.

- De Yong JP, Abadia Molina AC, Satoskar AR, et al. Development of chronic colitis is dependent on the cytokine MIF. Nat Immunol. 2001 Nov;2(11):1061–1066.

- Calandra T, Roger T. Macrophage migration inhibitory factor: A regulator of innate immunity. Nat Rev Immunol. 2003 Oct;3(10):791–800.

- Xia HH, Lam SK, Chan AO, et al. Macrophage migration inhibitory factor stimulated by Heliobacter pylori increases proliferation of gastric epithelial cells. World J Gastroenterol. 2005 Apr 7;11(13):1946–1950.

- van der Linden S, Valkenburg HA, Cats A. Evaluation of diagnostic criteria for ankylosing spondylitis. A proposal for modification of the New York criteria. Arthritis Rheum. 1984 Apr;27(4):361–368.

- Ward MM, Deodhar A, Akl EA, et al. American College of Rheumatology/Spondylitis Association of America/Spondyloarthritis Research and Treatment Network 2015 recommendations for the treatment of ankylosing spondylitis and nonradiographic axial spondyloarthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2016 Feb;68(2):282–298.