WASHINGTON, D.C.—Often, no clear explanation exists in neutrophilic dermatosis cases that links a patient’s skin disorder with an internal condition, expert Joseph Jorizzo, MD, professor, founder and former chair of the Dermatology Department at Wake Forest University in Winston-Salem, N.C., and professor of clinical dermatology at Wevascularill Cornell Medical College in New York, told attendees in the 2016 ACR/ARHP Annual Meeting session titled, Neutrophilic Dermatoses.

Neutrophilic Vascular Reactions

“One of the things I want to really highlight,” Dr. Jorizzo said, “is the difference between the kind of dermatoses where a clinical pathologic diagnosis ties together the patient’s internal complaints and their cutaneous findings, such as sarcoidosis or lupus or dermatomyositis, and focus on a prime category of reactive dermatoses.”

About half of patients in the “reactive” category will have no underlying disease, he said. The others may have a process that is caused by a reaction to a rheumatologic, gastroenterologic or myelodysplastic condition, or some other disorder.

“So [reactive diseases] require even more teamwork among colleagues than do the other diseases, where you just walk in, and the skin and inside is all together,” Dr. Jorizzo said.

These diseases, described as “neutrophilic vascular reactions” in a 1988 paper led by Dr. Jorizzo, include Sweet’s syndrome, Behçet’s disease, bowel-associated dermatosis-arthritis syndrome and pyoderma gangrenosum.1

“I like to include the word vascular, because I believe the neutrophilic process is vessel based, primarily, and that distinguishes this from diseases where the epidermis is the target, such as psoriasis,” Dr. Jorizzo said.

The biopsy is a crucial element in the diagnosis of these diseases, but getting one that’s actually helpful is not a simple proposition, he added.

“There’s a certain art in delivering to the pathologist [that which] gives you a chance of getting the diagnosis,” he said. “You want a lesion that’s just far enough advanced to have the classic changes, but not so far advanced that those changes are masked by secondary change.”

He also emphasized the concept of a therapeutic ladder—that the intensity of a therapy and the risk that’s willing to be tolerated—should be capped based on the extent of the disease.

Sweet’s Syndrome

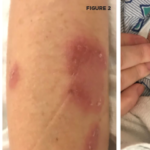

Sweet’s syndrome involves fever and malaise, along with erythematous plaques on clinical exam. Histologically, its traits include dense perivascular neutrophilic leukocytoclasia with minimal, or even no, evidence of vasculitis. Associated conditions can include infections, malignancies, inflammatory bowel disease and autoimmune disorders.

Dr. Jorizzo said thalidomide is often his preferred treatment for Sweet’s syndrome. This prescribed treatment can sometimes cause difficulties with health insurance companies because they might want an oncologist to approve the medication. Dr. Jorizzo mentioned a patient with whom this was the case. When the oncologist balked at the request, he sent the patient to him with a severe case of Sweet’s on the face, at which point the oncologist signed off right away.

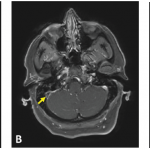

Behçet’s Disease

Behçet’s is a multisystem disease with many symptoms. Skin findings range from sterile papulopustules and palpable purpura to erythema nodosum-like lesions. On histology, a neutrophilic infiltrate will be seen, with leukocytoclastic vasculitis early in the disease course and lymphocytic vasculitis late in the course.