ORLANDO—In rheumatology, consults for muscle weakness and elevated creatinine kinase are common. The differential in these cases is broad, and when clinical history, laboratory studies and noninvasive testing fail to reveal a diagnosis, muscle biopsy can add valuable information. But to best use this information, we need to understand a bit about muscle pathology.

ORLANDO—In rheumatology, consults for muscle weakness and elevated creatinine kinase are common. The differential in these cases is broad, and when clinical history, laboratory studies and noninvasive testing fail to reveal a diagnosis, muscle biopsy can add valuable information. But to best use this information, we need to understand a bit about muscle pathology.

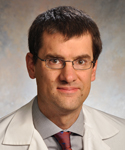

At the 2022 ACR Education Exchange, April 28–May 1, Peter Pytel, MD, professor of pathology, Department of Pathology, University of Chicago, shared his expertise.

Normal Muscle

Dr. Pytel began his talk with a review of normal muscle morphology. Normal skeletal muscle is composed of muscle fibers (cells) with peripheral nuclei and uniform size and cytoplasmic staining. Single muscle fibers are enwrapped in endomysium. Many muscle fibers are grouped into fascicles, which are enwrapped in perimysium. Normal fascicles don’t have visible connective tissue or inflammatory cells.

Muscle Disease

When assessing muscle tissue, pathologists first look for myopathic changes: muscle fiber necrosis and regeneration. “First, we look for muscle fiber necrosis and atrophy that points to a myopathic process. Then, we use an algorithmic approach to better understand what’s going on,” Dr. Pytel said. “We look for inflammation, vacuoles and inclusions. We look for fat replacement and fibrosis that occur when muscle’s capacity to regenerate is overwhelmed, indicating chronicity. Finally, we use various staining techniques to refine our understanding further.”1

Generally, inflammatory myopathy—the term used to refer to autoimmune processes affecting skeletal muscle—is inflammation plus myopathy. However, some processes lack visible inflammatory infiltrates, such as immune-mediated necrotizing myopathy.

“Other disease processes, such as infection [e.g., trichinosis] and dystrophies [e.g., dysferlin deficiency], can exhibit inflammation too, so it’s important to consider the clinical context,” Dr. Pytel said.

Autoimmune Inflammatory Myopathies

Dr. Pytel shared pearls of wisdom specific to the autoimmune inflammatory myopathies we treat most frequently.

Regarding dermatomyositis, the hallmark feature is perifascicular atrophy. When viewed under the microscope, muscle fibers near the edges of fascicles appear shrunken compared with healthy fibers at the center. Perimysial inflammation (e.g., around the fascicles) is also present.

“The perifascicular atrophy is far worse than the muscle necrosis,” Dr. Pytel said. “As for antisynthetase syndrome, add prominent necrotizing changes to the perifascicular atrophy we see in [dermatomyositis].”

When it comes to inclusion body myositis, the protracted clinical course is reflected in the biopsy. “We often see features of chronicity, like fibrosis and fatty replacement, that disrupts the normal fascicular architecture,” Dr. Pytel said.