In his recent movie, “Sicko,” the controversial director Michael Moore turned his attention to healthcare, specifically the difficulties in access to care faced by many Americans. I have reservations about Michael Moore’s tendency to overshoot his target and suspect that some parts of his documentaries are too contrived to be taken at face value. Nevertheless, this time he has definitely picked a topic of interest to ACR members, and indeed all healthcare professionals. The striking number of physicians in the theater when I saw “Sicko” supports that conclusion.

As ACR president, I am made aware of the concerns of ACR members through the numerous e-mails that stream in to our staff, the ACR list serve, and me personally, in addition to phone calls, letters, and encounters with colleagues in professional settings. On many topics—such as our educational meetings, our journals, and the Research and Education Foundation—the messages from ACR members are overwhelmingly positive and enthusiastic.

However, there is also palpable concern—and occasionally outright anger—about many aspects of the environment in which we care for our patients. Arguably, one could link many of our greatest challenges under the theme of “access to care,” and if I were a film director in the genre of Michael Moore, I would already have enough material to create my own documentary: “Sicko Rheum.”

It’s easy to list numerous access-to-care issues that have become areas of focus for our ACR staff—especially those who work with the Committee on Rheumatologic Care (CORC) and the Government Affairs Committee (GAC)—and for the CORC, GAC, and ACR Regional Advisory Council volunteers. These include absurd cuts to bone densitometry reimbursement, arbitrary and cynical denial of coverage by payers across the country for everything from anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide tests to medications to occupational or physical therapy, and the shortage of rheumatologists. And once more (when this column was written), we are facing the 500-pound gorilla of an impending 10% cut in Medicare payments that, if implemented, would threaten access to care for a large segment of the population and the viability of many rheumatology practices.

Stranger than Fiction

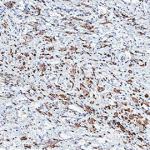

My personal Michael Moore moment occurred this past fall while rounding as attending physician on our rheumatology consult service. The case of “Mr. Wolverine” was especially interesting—high fevers, inflamed joints, occasional rashes, leukocytosis, and prominent elevation of acute phase reactants—the diagnosis was adult-onset Still’s disease. Our understanding of Still’s disease as an autoinflammatory, cytokine-driven disorder has advanced dramatically in recent years, thanks to brilliant research by ACR members such as Virginia Pascual, MD, of Baylor Institute for Immunology Research (Texas), and her colleagues, who have convincingly implicated interleukin 1 as a key mediator and therapeutic target in Still’s. While treatment approaches are evolving and several choices are reasonable in such a patient, use of the interleukin-1 receptor antagonist is emerging as a compelling option, notwithstanding the lack of definitive controlled trials which are very difficult to accomplish in rare conditions.

Mr. W provided a great opportunity to teach the fellows and residents about how the contrasts in the genetics, pathogenesis, and clinical manifestations of autoinflammatory versus autoimmune diseases gives us a unique vantage point from which to understand the distinct yet intersecting roles of the innate and adaptive arms of the immune response—an understanding that could guide us directly to our therapeutic choice, intravenous methylprednisolone plus subcutaneous anakinra. The clinical response was rapid and profound, and within a few days Mr. W was on oral prednisone, had learned how to self-inject his anakinra, and was ready for discharge. Also, one of the residents on the team told me she was now interested in a career in rheumatology.

So where is the “Michael Moore moment” in this happy chain of events? It happened soon after Mr. W’s discharge, when we learned that his prescription-drug insurance carrier had denied coverage for anakinra, the few doses sent home with Mr. W had all been used, and his fever and arthritis had returned. So the unfortunate Mr. W was readmitted to the hospital to be placed back on IV steroids and daily anakinra injections while we geared up to do battle with his prescription-drug insurance company.

We soon learned that Mr. W’s health insurance was with an HMO owned by the University of Michigan, which had not objected to his treatment with our biologic of choice when he was an inpatient. The problem was that Mr. W’s outpatient medications were controlled by a different carrier, which held a subcontract from his HMO and had its own ideas about which medications to authorize. This company informed us that anakinra was not a Food and Drug Administration–approved treatment for adult-onset Still’s disease, and that we could use it only after first attempting treatment with a long list of other medications—including essentially all DMARDs approved for RA treatment followed by, curiously, all of the other biologics approved for RA. If we disagreed, we could write a letter and it would be considered in due course.

With a patient who had experienced an unnecessary relapse and rehospitalization due to decisions made by people who, I was certain, had no clue what Still’s disease was, I was in an unusually testy mood as I sat down to compose the necessary letter. Addressing it “To whom it may concern,” I used relatively undiplomatic prose to make the obvious points that any practicing rheumatologist tries to communicate in such a situation. Finally, in an effort to impress or intimidate “whom it may concern,” I signed the letter not only as professor and chief of the division of rheumatology at the University of Michigan, but also as president-elect of the ACR. As I gave the letter to one of our clinic staff to fax to “whom it may concern,” I asked her to find out who would ultimately adjudicate the dispute. Who, indeed, had the final say in determining the fate of Mr. W?

“To Whom” Revealed

The answer came later that day, and was a stunner. To paraphrase my staff member, “Dr. Fox, Mr. W’s drug benefits company told us that, because they are a subcontractor to his HMO, which is owned by the University of Michigan, and because you are the designated expert of the University of Michigan Health System on the use of biologics in rheumatic diseases, you will have the final say in this dispute.” Despite my immediate embarrassment at having written an angry letter to myself and recollections of Walt Kelly’s comic strip “Pogo,” known for the line, “We have met the enemy and they are us,” my reaction was naive relief, assuming that Mr. W’s anakinra would be promptly authorized. Such optimism was shattered by the next piece of news: “The insurer told us that, even though you are the final authority in this matter, your letter must first proceed through multiple levels of review, and that you can’t intervene until all those reviews have run their course.” I had written an angry letter to myself, but was not allowed to respond or take appropriate action.

Now began the war of attrition, in which our goal was to accelerate the review process through all necessary levels. The fight would frustrate us so many times that we would eventually give up due to exhaustion. We were instructed to begin by re-faxing all records pertaining to Mr. W to the insurer, which was done. Evasive maneuvers followed: claims that our faxes had not been received, that our phone calls had never been made, and that our rheumatology clinic personnel were lying about the entire matter. Meanwhile, Mr. W, whose Still’s disease was again under control and who was ready for discharge, languished in the hospital awaiting resolution of this dispute. After the efforts of our resourceful clinic staff proved to be unsuccessful, one of our fellows took on the role of master telephone diplomat and, miraculously, authorization came through by the end of the week. Mr. W was discharged and has done well since.

This happy ending only partly mitigates an absurd yet all-too-typical example of what the rheumatologist encounters when he or she tries to translate the stunning scientific and clinical advances in our field into optimal care. And most ACR members don’t have a cadre of support staff and fellows, along with institutional clout, to assist them in battling the often arbitrary and illogical decisions of those who pay for and profit from the care of our patients. Without these advantages I might never have been able to obtain appropriate treatment for Mr. W.

In future columns, I will go into detail about how the ACR is taking action to respond to access-to-care challenges. As always, I welcome comments and suggestions from ACR/ARHP members about this important issue.

Epilogue

- I never received an answer to my letter.

- Mr. W’s HMO has been sold (for about a quarter of a billion dollars) to a commercial insurance carrier and no longer exists. My role as an advisor to this HMO regarding treatment for rheumatic diseases has been eliminated.

- The consult team resident who helped care for Mr. W has decided to apply for a rheumatology fellowship in our unit.

Dr. Fox is president of the ACR. Contact him via e-mail at [email protected].