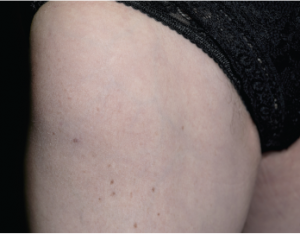

Close-up of the thigh of a 67-year-old female patient with focal myositis of unknown cause.

Bacho/shutterstock.com

CHICAGO—On a Saturday morning in Chicago, Chester V. Oddis, MD, director of the Myositis Center at the University of Pittsburgh, explained to a crowded room of about 500 rheumatologists attending the ACR’s State-of-the-Art Clinical Symposium in April how best to use myositis autoantibodies in clinical care.

He began with an overview of the different types of myositis and explained that patients with myositis are symmetrically weak and meet several diagnostic criteria. Specifically, they may have elevated serum enzymes, such as creatine kinase (CK), aldolase, aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH). They also have myopathic electromyographic abnormalities, such as sharp waves, fibrillations and polyphasic motor units. Finally, they have muscle pathology that is characterized by myofiber degeneration/regeneration, mononuclear cell infiltrates and perifascicular atrophy.

Many patients with myositis also have rashes and are thus diagnosed with dermatomyositis (DM), which is a much easier diagnosis to make than polymyositis (PM), which represents a diagnostic challenge. This is because there are many mimics of PM and therefore a muscle biopsy is necessary for its diagnosis. In particular, PM has histologic features that distinguish it from dermatomyositis. Histology reveals that “from a histopathological perspective, PM and DM are almost like different diseases in their own rights,” noted Dr. Oddis. “If you look at the histology, even from a distance, they look different,” he explained, pointing to the two histological examples projected onto the large screens.

Statins & Myopathy

Dr. Oddis transitioned from this overview to an example of a newer autoantibody marker for myositis. In this case, the autoantibody is triggered by the use of statins, which are increasingly prescribed around the world. Rheumatologists have noted that “lots of patients on statins get muscle symptoms,” explained Dr. Oddis. Some of these patients get referred to rheumatology.

When Dr. Oddis sees a patient with statin-induced muscle symptoms and/or increased levels of creatine kinase (CK), he discontinues the statin. In many cases, the symptoms normalize, and Dr. Oddis does not perform a workup. Instead, he recommends that the referring physician prescribe a different statin or cholesterol-lowering agent to the patient. In some cases, however, he found that the symptoms persisted and/or the CK remained elevated even after the statin was discontinued. “I was seeing patients where I thought, ‘Geez, there is something else going on,’” noted Dr. Oddis.

He described one of these patients in detail to the audience. She was a 67-year-old Caucasian woman with hypertension, hyperlipidemia and uterine cancer. In 2004, she was prescribed atorvastatin, and in 2008, she experienced lower extremity weakness. By 2009, she had difficulty walking up steps and lifting her arms over her head. She stopped the atorvastatin on her own, but saw no improvements in weakness. Blood tests revealed CKs of 6473 and then 9375, and she was admitted to the hospital, where a muscle biopsy revealed myonecrosis with many necrotic fibers. There was, however, no inflammation or vasculitis. Dr. Oddis treated her with prednisone and saw improvements in her CK level and muscle weakness. Unfortunately, when he tapered the prednisone, the CK levels went back up. There were no other autoimmune manifestations and no family history of autoimmune disease. She also did not have the rashes that are characteristic of DM. He diagnosed her with statin myopathy, but the patient was reluctant to increase her prednisone dose.

‘From a histopathological perspective, PM & DM are almost like different diseases in their own rights. If you look at the histology, even from a distance, they look different,’ Dr. Oddis explained, pointing to the two histological examples projected onto the large screens.

Around this time, there were descriptions in the medical literature of immune-mediated necrotizing myopathy associated with statins. These patients presented with proximal weakness during or after statin use. The patients had elevated CK, and their persistent weakness and elevated CK continued despite stopping the statin. The patients did improve, however, with immunosuppressive agents. This improvement occurred despite the fact that muscle biopsies revealed necrotizing myopathy in the absence of significant inflammation. These observations led many rheumatologists to question whether these patients actually had PM.

Further research revealed the presence of autoantibodies to 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-coenzyme A reductase (HMGCR), the pharmacologic target of statins. Patients with this autoantibody were weak and had an elevated CK and appeared to represent a subgroup of necrotizing myopathy (NM). Moreover, the majority of patients had been exposed to statin prior to the onset of weakness. All of the patients responded to immunosuppressant therapy, and many relapsed when the immunosuppressant therapy was terminated. Taken together, the data suggested that the autoantibody to HMGCR was driving statin-associated NM.

Dr. Oddis then circled back to his patient and found that she was, indeed, positive for the anti-HMGCR autoantibody. Her weakness progressed over time, and at that point in the case history, she had a CK of 6367. Dr. Oddis increased her prednisone and added methotrexate. He then decreased prednisone and added Imuran/methotrexate. A month later, he added intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG), and two months later, he saw that not only had her muscle weakness clearly improved, but she had her first normal CK reading. When her strength returned, he tapered her IVIG, but did not take her off of it completely. He discontinued Imuran and prednisone. He noted that she has been maintained on that regimen for five years, and although her CK levels have increased over time and remain elevated, her strength is acceptable and her health can be managed on methotrexate and IVIG.

Conclusion

Dr. Oddis concluded his presentation by calling on rheumatologists to recognize the clusters of symptoms that may reflect an autoantibody-associated systemic autoimmune rheumatic disease. These autoantibodies may accompany statin use, or they may be associated with lung disease. In particular, he drew the audience’s attention to the possibility of autoimmune interstitial lung disease contributing to systemic disease.

Lara C. Pullen, PhD, is a medical writer based in the Chicago area.