Tashatuvango / shutterstock.com

The idiopathic inflammatory myopathies (IIM) encompass eight categories: 1) dermatomyositis (DM) in adults, 2) juvenile dermatomyositis, 3) amyopathic DM, 4) cancer-associated DM, 5) polymyositis, 6) immune-mediated necrotizing myopathy, 7) inclusion body myositis, and 8) overlap myositis.1 These categories help classify the myopathies based on clinical and histologic features. The incidence of IIM is estimated at 2–15 new cases per year per million inhabitants, depending on country, with a peak range of onset in adults between 45 and 60 years old.1,2

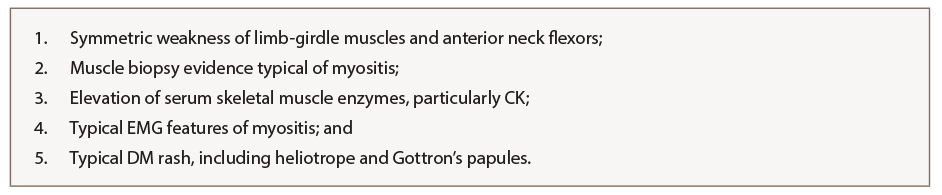

One of the most widely used classification criteria for myositis was described by Bohan and Peter in 1975.3 Depending on the number of criteria fulfilled, a diagnosis of polymyositis or dermatomyositis can be made. These criteria incorporate clinical features of weakness, histopathologic evidence on muscle biopsy, elevation of skeletal muscle enzymes, features on electromyogram (EMG) and cutaneous manifestations (see Table 1). Importantly, use of these criteria first requires exclusion of other potential myopathies, including muscular dystrophy; neurologic disease, including myasthenia gravis; metabolic or endocrine myopathies; and infectious myositis.

Reclassification of Inflammatory Myopathies

Since 1975, various attempts at reclassification of inflammatory myopathies have incorporated inclusion body myositis and immune-mediated necrotizing myopathy, once these entities were recognized. In 2004, the International Myositis Classification Criteria Project was established, which included experts across multiple adult and pediatric subspecialties (i.e., rheumatology, neurology, dermatology). The project involved collecting data between 2008 and 2011 from more than 975 patients with IIM (75% adults and 25% children), with 624 having mimicker conditions, or non-IIM. Statistical models helped identify 16 variables from six different categories that were helpful in distinguishing IIM from mimicking comparators.

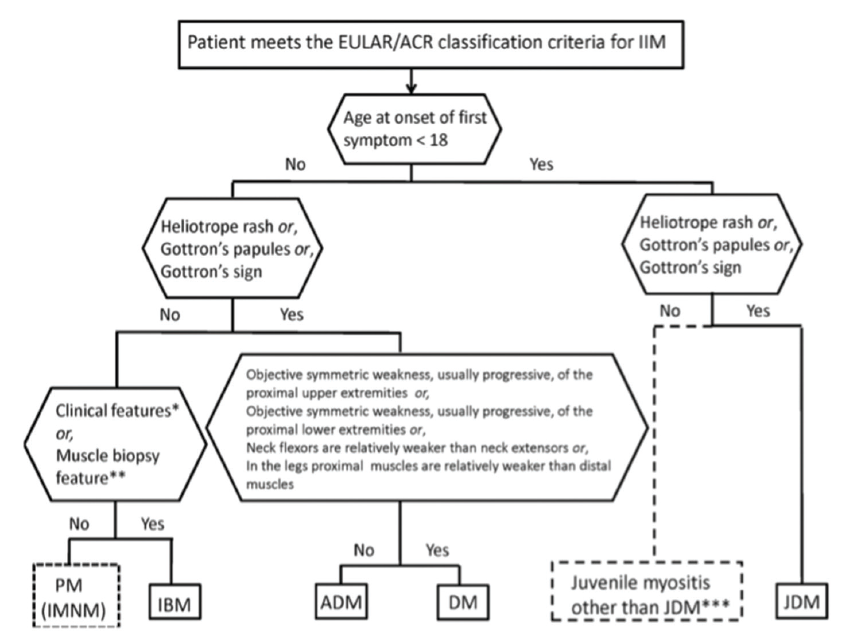

Based on statistical results, a scoring system was created in which points are added to yield a probability of having IIM. The scoring system incorporates cutaneous manifestations; laboratory measurements, such as muscle enzymes and presence of anti-Jo-1 autoantibodies; clinical manifestations; and muscle biopsy features. With muscle biopsy, the 2017 European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR)/ACR classification criteria have much improved sensitivity (93%) and specificity (88%) over prior classification criteria.4 Once a patient first meets EULAR/ACR classification criteria for IIM (probability ≥55%), a classification tree for subgroups of IIM was developed (see Figure 1, and Table 2) to further subclassify the patient. An online calculator IIM is available to help clinicians use the new classification criteria.

(click for larger image) Figure 1: Classification Tree for Subgroups of Idiopathic Inflammatory Myopathies4

Novel Autoantibodies

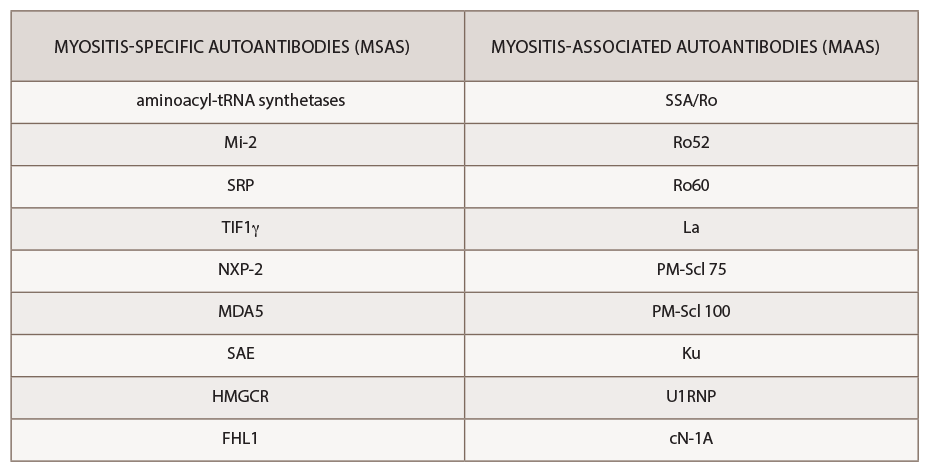

The past decade has seen an increasing recognition of novel autoantibodies identified in types of inflammatory myopathy. Autoantibodies divide into two classifications: myositis-specific antibodies (MSAs), which are almost exclusively present in IIM, and myositis-associated antibodies (MAAs), which are present in other systemic autoimmune diseases (see Table 3). Myositis-specific antibodies can be tested by ordering myositis antibody panels available commercially. Based on published literature, MSAs or disease-specific antibodies can be identified in over 70% of patients with IIM.5

Interestingly, myositis-specific antibodies are closely associated with distinct clinical phenotypes and can help predict potential complications. Because myositis antibody panels can take up to several weeks to return, recognition of these clinical manifestations can identify disease subtypes early and help clinicians screen for associated complications. Recent studies have analyzed serologic data from inflammatory myositis cohorts, which have helped establish some of the clinical phenotypes associated with specific MSAs. An understanding of unique cutaneous manifestations associated with some of these antibody subtypes is emerging.

One of the leading researchers in this field is David Fiorentino, MD, PhD, professor of dermatology and director of a multidisciplinary rheumatology-dermatology clinic at Stanford University, Stanford, Calif. Dr. Fiorentino published some of the initial literature describing the clinical phenotype associated with anti-melanoma differentiation-associated gene 5 (anti-MDA5), a type of clinically amyopathic dermatomyositis.

Improved phenotyping of myositis patients in the past decade has enabled us to better understand unique clinical associations.

Retrospectively, plasma samples from 77 patients with dermatomyositis were collected from outpatient clinics at a tertiary medical center. Dr. Fiorentino’s group compared patients with anti-MDA5 antibodies (n=10) with those who were anti-MDA5 negative (n=67) and found the following clinical findings to be statistically associated with MDA5 positivity: interstitial lung disease, hand swelling, arthritis/arthralgias, clinically amyopathic dermatomyositis, skin ulceration, palmar papules, mechanic’s hands, panniculitis, alopecia, oral pain/ulcers and violaceous erythema of the elbow/knee.6 This systemic investigation ultimately helped identify the unique association of cutaneous ulcerations and palmar papules with MDA5 myositis.

More Nuanced Understanding

When initially pursuing this study, Dr. Fiorentino wanted to characterize the clinical features of patients with MDA5 myositis. He states none of the characteristics they thought may be present, such as Gottron’s papules or heliotrope rash, was seen in this subset of patients, and instead they noted an association with oral ulcers and palmar lesions.

Dr. Fiorentino explains how the findings started from the basis of simple clinical observation: “The most rewarding part is when we discovered this, it had nothing to do with mining a database and looking for a P value.”

He states that one of the areas of change in the past 10 years in myositis is a more nuanced understanding of the meaning of myositis antibodies. Each subgroup of antibodies has a lot of heterogeneity, Dr. Fiorentino says, “with interaction of genetics and environment ultimately leading to the particular phenotype.”

Lisa Christopher-Stine, MD, MPH, associate professor of medicine and neurology and director of the Johns Hopkins Myositis Center at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, says Dr. Fiorentino’s specialization at the intersection of dermatology and rheumatology offers a unique vantage point. “For years, I noticed a subset of patients with DM with rash on the palms, which I jokingly termed inverse Gottron’s papules,” she says, which later was recognized as the palmar papulosis seen in MDA5 disease. “It took the careful eye of a dermatologist [Dr. Fiorentino] to recognize those subtle cutaneous differences that define dermatomyositis beyond Gottron’s papules. David Fiorentino’s work was remarkable and pivotal, teaching us that not all dermatomyositis rashes are the same.”

Since 1975, various attempts at reclassification of inflammatory myopathies have incorporated inclusion body myositis & immune-mediated necrotizing myopathy.

Ferritin as a Prognostic Indicator

Other studies have also sought to better characterize differences even within the subset of anti-MDA5 myositis patients. A retrospective study from Japan by Gono et al. evaluated 27 patients with dermatomyositis who were positive for anti-MDA5 antibody. They stratified these patients into those with (n=20) and without (n=7) rapidly progressive interstitial lung disease (ILD) and compared them. A statistically significant difference in ferritin levels between the two groups was noted, with higher ferritin in those with rapidly progressive ILD (mean of 835 ng/mL) compared to those without ILD (186 ng/mL). Because no significant difference in C-reactive protein was seen between these groups, the researchers hypothesized the hyperferritinemia is not simply a reflection of acute phase reactant response, but pathologic.

The researchers also compared those patients with MDA5 antibody and rapidly progressive ILD who lived (n=11) with those who died (n=9). They found those who died had higher ferritin (1,600 ng/mL) levels than those who lived (409 ng/mL), a difference that reached statistical significance (P=0.017).7 This helped establish ferritin as a prognostic indicator in patients with clinically amyopathic DM with MDA5 positivity.

Studies have demonstrated that serum IL-18 levels are higher in patients with dermatomyositis and are associated with developing ILD and more severe disease activity.1 Interestingly, high levels of ferritin and IL-18 are implicated in macrophage activation syndrome (MAS), and MDA5 encodes an RNA-specific helicase that functions to recognize single-stranded RNA (ssRNA) viruses, leading some to hypothesize anti-MDA5 myositis as a form of MAS targeting skin and lungs related to an infectious trigger.11

Ovoid Palatal Patch

In 2016, Dr. Fiorentino also described a novel palatal lesion in dermatomyositis that he termed the ovoid palatal patch. He says his team would look for perioral manifestations described in the literature, including gum telangiectasias and gum erythema, but rarely saw them in the clinic.

“In a few patients, I noticed a distinctive look of semicircular, symmetric erythema always positioned in the same place in the palate,” he says.

To determine the significance of this cutaneous lesion, Dr. Fiorentino and his team evaluated 45 patients who met criteria for dermatomyositis seen in the outpatient clinic over a five-month period from 2014 to 2015. The study found 40% of the patients had an ovoid palatal patch. He and his team wanted to see whether the presence of the patch was associated with any specific clinical or laboratory findings. Comparing the clinical findings of patients with this palatal lesion to those without, they found the patch had a statistically significant association with the presence of transcription intermediary factor 1-γ (TIF1-γ) antibodies, as well as clinically amyopathic disease and cancer-associated dermatomyositis.8

This study helped further improve the characterization of the TIF1-γ antibody phenotype, including an association with malignancy and the ovoid palatal patch. Dr. Christopher-Stine calls the TIF1-γ association being described practice changing: “I look more closely at the palates of patients than I ever did before.”

Additional Autoantibodies

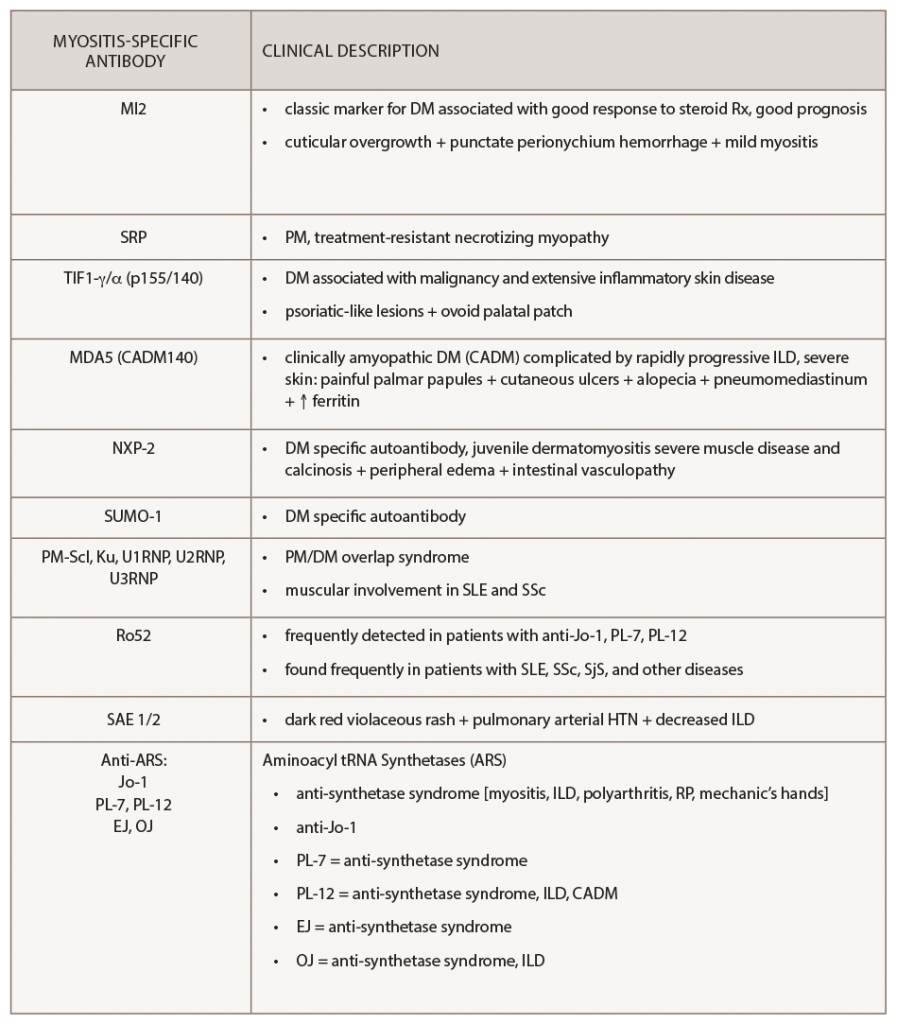

Several other autoantibodies are associated with unique cutaneous phenotypes. As described, anti-MDA-5 can present with painful palmar papules or ulcerations, arthritis or alopecia. Anti-small ubiquitin-like modifier activating enzyme heterodimer (anti-SAE) is reported to manifest a dark violaceous or red rash and has been associated with pulmonary arterial hypertension, particularly in Chinese populations. Anti-Mi-2 can cause punctate perionychium hemorrhage and cuticular overgrowth. Anti-TIF1-γ, reviewed above, is associated with the ovoid palatal patch and can have psoriasis-like lesions. Anti-nuclear matrix protein 2 (anti-NXP-2) can cause severe calcinosis, associated peripheral edema or intestinal vasculopathy.9

Table 3 summarizes the cutaneous and other clinical manifestations associated with particular myositis-specific antibodies that have been reported in the literature.

Cardiac Involvement

Dr. Christopher-Stine has also described an even rarer antibody/phenotype association seen in the setting of inflammatory myopathies: an association between severe cardiac involvement in a subgroup of myositis patients with positive antimitochondrial antibodies (AMAs). The AMAs were checked in a few myositis patients with primary biliary cirrhosis, scleroderma overlap, or as part of transaminitis workup. She noticed that several patients with severe cardiac disease requiring implantable cardioverter-defibrillators (ICDs) or defibrillators had AMAs, which she found unusual since almost none of the other patients in the cohort required defibrillators/ICDs. Her team performed a retrospective case series looking at more than 1,000 patients who underwent myositis autoantibody testing, finding seven with positive AMAs by confirmatory enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). Although this is a very small cohort, the researchers found a striking clinical feature of severe cardiac involvement in the majority of the patients (~70%) including severe conduction abnormalities, arrhythmias, cardiomyopathy and myocarditis.12 These patients also often had chronic skeletal muscle disease, including muscle atrophy.

The findings are diluted when looking at the cohort as a whole, Dr. Christopher-Stine explains. “Antimitochondrial antibodies are seen in other patients, and it is only a subset who go on to develop cardiac disease, one of the highest morbidity features.” She notes the cardiomyopathy seems to be responsive to treatment with immunosuppression. “We don’t fully understand how to predict which of the positive AMA patients will go on to develop cardiac involvement.”

The improved phenotyping of myositis patients in the past decade has enabled us to better understand unique clinical associations, with implications in how we evaluate and manage idiopathic inflammatory myositis. Dr. Christopher-Stine notes inflammatory myopathies are “one of the most carefully phenotyped groups of the rheumatic diseases” and the antibody/phenotype correlations have helped improve diagnostic accuracy and changed management in unique subsets.

Next Steps

A wide spectrum of clinical manifestations is seen in idiopathic inflammatory myositis, but the underlying pathogenesis is still murky. Dr. Fiorentino says one of the next steps in myositis research is understanding the biology of these antigens.

“We need to understand where these antigens are and in which types of cells. Antigen structure is going to play a large role in understanding how the immune response is being generated in the tissue,” he says. “We don’t understand why these antibodies are generated against proteins which are ubiquitously expressed in all of our tissues.”

Dr. Christopher-Stine anticipates a role for precision medicine in the future of the field: “Precision medicine is most exciting on two fronts: fine-tuning which patients will develop which complications and designing better treatment algorithms.” She explains how further genomic studies may allow for a more personalized selection of immunosuppressant therapy. Additionally, she believes we can improve the criteria for inflammatory myopathies. The 2017 ACR/EULAR Criteria for Idiopathic Inflammatory Myopathies include only one myositis-specific antibody, anti-Jo1.

“I think we can go a step further, since autoantibodies drive the phenotypes so strongly, yet they were not included,” says Dr. Christopher-Stine.

An appreciation for the cutaneous and other clinical manifestations associated with myositis-specific antibodies has implications for diagnosis and management, particularly with rarer subtypes of idiopathic inflammatory myopathies. When evaluating a patient with suspected inflammatory myopathy, cutaneous ulcerations or palmar papules should raise concern for possible MDA5-associated dermatomyositis, and an ovoid palatal lesion should raise suspicion for possible TIF1-γ-associated myositis. The presence of certain myositis-specific antibodies requires additional management considerations, including cancer screening in TIF1-γ patients given the strong association with malignancy in those patients. By further identifying and studying these novel phenotypes associated with myositis antibodies in IIM, we can substratify patients and better understand the underlying disease pathogenesis and potential therapeutic targets.

Mithu Maheswaranathan, MD, is a rheumatology fellow at Duke University Medical Center, Durham, N.C.

Mithu Maheswaranathan, MD, is a rheumatology fellow at Duke University Medical Center, Durham, N.C.

Lisa Criscione-Schreiber, MD, MEd, is associate professor of medicine at Duke University School of Medicine, Durham, N.C.

Lisa Criscione-Schreiber, MD, MEd, is associate professor of medicine at Duke University School of Medicine, Durham, N.C.

Classification Criteria

Review the 2017 European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR)/ACR classification criteria.

All the ACR-endorsed criteria.

References

- Merlo G, Clapasson A, Cozzani E, et al. Specific autoantibodies in dermatomyositis: a helpful tool to classify different clinical subsets. Arch Dermatol Res. 2017 Mar;309(2):87–95. Epub 2016 Dec 7.

- Oldroyd A, Lilleker J, Chinoy H. Idiopathic inflammatory myopathies—a guide to subtypes, diagnostic approach and treatment. Clin Med (Lond). 2017 Jul;17(4):322–328.

- Bohan A, Peter JB. Polymyositis and dermatomyositis (first of two parts). N Engl J Med. 1975 Feb 13;292(7):344–347.

- Lundberg IE, Tjärnlund A, Bottai M, et al. 2017 European League Against Rheumatism/American College of Rheumatology classification criteria for adult and juvenile idiopathic inflammatory myopathies and their major subgroups. Ann Rheum Dis. 2017 Dec;76(12):1955–1964.

- Fujimoto M, Watanabe R, Ishitsuka Y, et al. Recent advances in dermatomyositis-specific autoantibodies. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2016 Nov;28(6):636–644.

- Fiorentino D, Chung L, Zwerner J, et al. The mucocutaneous and systemic phenotype of dermatomyositis patients with antibodies to MDA5 (CADM-140): A retrospective study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011 Jul;65(1):25–34.

- Gono T, Sato S, Kawaguchi Y, et al. Anti-MDA5 antibody, ferritin and IL-18 are useful for the evaluation of response to treatment in interstitial lung disease with anti-MDA5 antibody-positive dermatomyositis. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2012 Sep;51(9):1563–1570.

- Bernet LL, Lewis MA, Rieger KE, et al. Ovoid palatal patch in dermatomyositis: A novel finding associated with anti-TIF1γ (p155) antibodies. JAMA Dermatol. 2016 Sep 1;152(9):1049–1051.

- Wolstencroft PW, Fiorentino DF. Dermatomyositis clinical and pathological phenotypes associated with myositis-specific autoantibodies. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2018 Apr;20(5):28.

- Yang Y, Yin G, Hao J, et al. Serum interleukin-18 level is associated with disease activity and interstitial lung disease in patients with dermatomyositis. Arch Rheumatol. 2017 Apr 11;32(3):181–188.

- Moghadam-Kia S, Oddis CV, Aggarwal R. Anti-MDA5 antibody spectrum in Western World. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2018 Oct 31;

20(12):78. - Albayda J, Khan A, Casciola-Rosen L, et al. Inflammatory myopathy associated with anti-mitochondrial antibodies: A distinct phenotype with cardiac involvement. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2018 Feb;47(4):552–556.