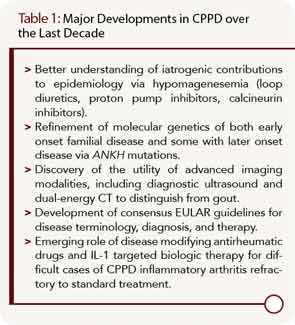

Calcium pyrophosphate dihydrate crystal deposition (CPPD) is a very common radiographic finding in aging and osteoarthritic joint cartilages. In some patients, CPPD manifests clinically as acute or chronic inflammatory arthritis, and CPPD can promote degenerative joint disease. Management of acute inflammatory arthritis in CPPD stems primarily from treatments used for acute gouty arthritis. Some disease-modifying agents used in rheumatoid arthritis (RA) have been studied in chronic inflammatory synovitis in CPPD, but without the benefit of randomized, controlled trials. There remains an unmet need for agents to prevent and lessen deposits of calcium pyrophosphate dihydrate crystals in those patients with chronic inflammatory arthritis and/or advanced degenerative arthritis driven by the crystals. This situation is in stark contrast to the growing array of therapeutic options to decrease urate crystal burden by targeting hyperuricemia in gout. In this article, I discuss progress in CPPD research, outcomes, diagnosis, and treatment over the last decade (see Table 1).

Developments in CPPD Epidemiology

In most patients, CPPD appears to represent a systemic articular and soft tissue pathophysiology disorder in aging, a paradigm reinforced by the results of the unique Genetics of Osteoarthritis and Lifestyle study cohort (GOAL).1,2 In GOAL, radiographic evidence of CPPD at one joint was frequently associated with CPPD at distant joints, whether osteoarthritis (OA) was present or not.2 One unexpected nuance of GOAL was that knee OA, but not hip OA, was associated with radiographic evidence of CPPD at distant joints.2

True prevalence of CPPD as a pathologic finding, let alone symptomatic arthritis, has not yet been reliably measured. This is due to limits of both survey methods and plain radiographic detection, and is highlighted by findings of plain radiographs of knees, hands, and pelvis in roughly equal-sized, large groups with clinically severe hip OA, clinically severe knee OA (defined as radiographic OA, and needing joint arthroplasty), and without knee or hip OA in GOAL.1,2 The knee is the most common site of radiographic chondrocalcinosis, but 42% of the chondrocalcinosis cases in GOAL had no knee involvement.1 This underscores the need, in clinical practice, to do thorough, joint-specific screening for CPPD, where appropriate, rather than knee radiographs to rule in or rule out CPPD at distant joints.

Environmental and genetic factors likely underlie differences in development and clinical phenotype of CPPD in populations. In this context, a markedly decreased prevalence of CPPD in a random sample of Chinese patients aged 60 years and older in Beijing, China, compared to a control population of white patients in Framingham, Mass., is surprising, given the excess of knee OA in the Chinese group of this study cohort.3 Environmental influences on CPPD could include dietary mineral content and other factors regulating body iron, calcium, phosphate, and magnesium stores, and parathyroid function and catalytic activity of enzymes that regulate inorganic pyrophosphate (PPi) formation and hydrolysis.3 Acquired and genetic factors likely include effects of dysregulated mitochondrial function on adenosine triphosphate (ATP) and PPi metabolism in aging and OA.4,5