CPPD is likely a biomarker of cartilage aging in most circumstances, and, in OA, CPPD may be a biomarker of a dysregulated, but functionally significant, cartilage repair response, and of noxious effects of excess extracellular PPi independent of crystal deposition.8 However, this does not mean that CPPD is simply an epiphenomenon. An illustrative parallel is the dual implication, as biomarker and mediator of tissue complications, of basic calcium phosphate crystal deposition in OA, tendinopathies such as shoulder-rotator-cuff disease, and in arteries in atherosclerosis and diabetic and end-stage renal disease arteriopathies.

Emerging Trends in CPPD Diagnosis

Major advances in CPPD diagnostics include formal recognition by EULAR of the utility of high-resolution ultrasound, now a standard tool for gout diagnosis.14 Ultrasound is convenient, inexpensive, does not involve radiation, picks up even subtle joint inflammation, correlates with positive results by synovial fluid crystal analysis, and can differentiate between gout and CPPD in most circumstances.7 In addition, ultrasound can detect CPPD even in the absence of chondrocalcinosis by plain radiography (see Figure 2).17

Preliminary criteria proposed for CPPD by ultrasound have been published.17 However, false positives and negatives can occur. The approach is best for CPPD detection in fibrocartilages and in middle zones of articular hyaline cartilages. Diagnostic value for CPPD disease in studies of plantar fascia and tendons such as the Achilles remains unclear. Whether dual-energy computed tomography (CT) can be usefully applied to CPPD diagnosis is not resolved, and magnetic resonance imaging is not yet optimized for diagnosis of CPPD.

Rheumatologists increasingly recognize that CPPD is a tremendous disease mimic, going well beyond gout, OA, RA, and septic arthritis to include polymyalgia rheumatica and meningitis.14,15 Given that CPPD is so common, accurate exclusion of entities other than CPPD is accepted clinical practice in acute and chronic arthropathies in which CPPD is present. In particular, since infectious arthritis can coexist with CPPD and gout, imaging approaches do not render synovial fluid analysis obsolete in the diagnosis of acute inflammatory arthritis.

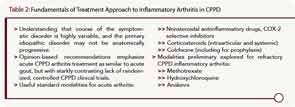

Current and Emerging Treatment for CPPD Clinical Manifestations

EULAR-expert, opinion-based recommendations emphasize that treatment of acute CPPD arthritis is similar to that for acute gout, but with a starkly contrasting lack of randomized, controlled clinical trials for CPPD.18 There are many available modalities (see Table 2). For example, intraarticular steroids are useful, particularly in elderly subjects with multiple comorbidities.15,18 Likely benefits exist for prophylaxis of acute CPPD with low-dose colchicine, and practitioners need to be aware of risks for precipitating acute CPPD arthritis in the postoperative state (including postparathroidectomy, and in affected knee joints after arthroplasty) and after injecting intraarticular hyaluronan, or prescribing bisphosphonates or granulocyte colony–stimulating factor (G-CSF).15