Studies highlighting the large numbers of people affected by knee osteoarthritis (OA) point to what clinicians who treat knee OA have been seeing for the past few decades: a substantial increase in the prevalence of knee OA in the U.S. and globally. Roughly 250 million people are affected by knee OA worldwide, and about 14 million people in the U.S. have been diagnosed with the disease in the past 20 years.1,2

This high prevalence of knee OA is fairly new, and its rapid rise over the past several decades coincides with two emerging realities of contemporary life: People are living longer and living heavier. Most studies suggest that the increased prevalence of knee OA during the past several decades correlates with both an aging population as well as rising obesity. It is widely thought that knee OA is a function of age and weight, making it only marginally preventable.

“People tend to think of knee OA as related to age and body mass index (BMI); you can’t control aging, and the obesity epidemic has been pretty intractable,” says Ian Wallace, PhD, who works in the Department of Human Evolutionary Biology at Harvard University in Cambridge, Mass. “People have really started to almost think of knee OA as an unmanageable disease; once you get it, you either begin taking pain medication, or if you have good insurance, you get a knee replacement.”

But is this the full picture?

Dr. Wallace doesn’t believe so. As a paleoanthropologist, he is used to looking at things through a long lens, as he and his colleagues did recently in a study that reached back to prehistoric times to gain insight into the etiology of knee OA and better understand its current high prevalence.3 That they found near double the rate of knee OA over the past 50 years compared with past ages is not surprising, but what is surprising, he says, is the finding that age and weight may not explain the whole picture of why the prevalence has increased so drastically in current times.

Tefi / shutterstock.com

“We found that knee osteoarthritis is far more common [now] than in the past,” says Dr. Wallace. “But the surprising finding is that it is not completely due to the two risk factors of age and BMI.”

This high prevalence of knee OA … coincides with two emerging realities of contemporary life: People are living longer & living heavier.

Learning from the Past

Dr. Wallace

As a paleoanthropologist, Dr. Wallace is interested in the evolutionary history of certain diseases, particularly those common today but not as common in the past. Called mismatch diseases, these afflictions common in contemporary culture are attributed to current lifestyles that differ from the conditions under which humans evolved. Diabetes is an example of a mismatch disease.

Recognizing that knee OA may be one of these mismatch diseases, Dr. Wallace and his colleagues undertook the study to examine the long-term trends in knee OA prevalence in the U.S., and to look at how the prevalence has changed from prehistoric times to today.

The researchers looked at cadaver-derived skeletons of people aged 50 years and older from three different time periods: a prehistoric period (i.e., 6,000–300 years ago); the early industrial period (i.e., the 1800s to the early 1900s); and the modern post-industrial period (i.e., the late 1900s to the early 2000s). The 176 skeletons examined from the prehistoric period came from Native American hunter-gatherers and early farmers. The 1,581 skeletons examined from the early industrial period came from individuals who lived in Cleveland, Ohio, and St. Louis, Mo., and the 819 skeletons examined from the modern, post-industrial period came from people who lived in Albuquerque, N.M., and Knoxville, Tenn.

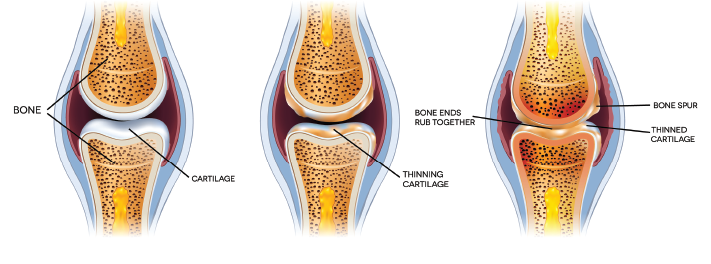

Knee OA was identified in the skeletal samples based on the presence of eburnation (i.e., polish from bone-on-bone contact). The study found the prevalence of knee OA was significantly higher among skeletal samples from the post-industrial period compared with the two earlier periods. After controlling for sex, the prevalence of knee OA found in the post-industrial skeletal samples measured 2.6 times higher than in the early industrial period (i.e., 16% vs. 6%; P<0.001) and two times higher than in the prehistoric period (i.e., 16% vs. 8%; P=0.003).

To examine whether the current knee OA prevalence is attributable to age and BMI, the authors analyzed a subset of skeletal samples for whom age and BMI data were available (which only occurred with the skeletal samples from the early and post-industrial periods). After controlling for age and BMI, the prevalence of knee OA remained 2.1 times higher in the skeletal samples from the postindustrial period compared to skeletal samples for the early industrial period (i.e., 11% vs. 5%; P<0.001).

“The surprising result is that even after you adjust for BMI and age, the increase in prevalence persists,” says David Felson, MD, who works with the Clinical Epidemiology Research & Training Unit at the Boston University School of Medicine.

Dr. Felson, a co-author who has expertise in OA clinical research, emphasizes, however, that despite controlling for BMI in the study, he believes weight remains an important risk factor.

“Earlier populations were really much thinner than our more recent and current populations,” he says. “I think weight is still an important factor [because] obesity is such a big risk factor for arthritis. I think it does probably explain some of the increase in prevalence even though we tried to adjust for that.”

However, Dr. Felson acknowledges the study raises important questions about other possible risk factors that remain largely unrecognized. The study paid close attention to one in particular: physical activity.

Physical Activity & Knee OA

Although the study did not look at physical activity or other potential risk factors, the finding that the prevalence of knee OA has doubled since early times even after controlling for BMI and age allowed the authors to hypothesize that perhaps physical activity is a risk factor.

“Our data suggest that rather than physical activity being bad for our joints, it actually may be good, particularly during the growing years when a person is developing cartilage and bone,” says Dr. Wallace.

Dr. Callahan

According to Dr. Wallace, although the common assumption is that knee OA is related to wear and tear of the joint (through age and weight), the study results suggest the opposite is possible. “If knee OA is simply a matter of wearing out your joints, then we’d expect the prevalence would have been going down since World War II because, if anything, physical activity declined in the 20th century,” he says. “So it doesn’t make sense that knee OA is solely due to wear and tear when the prevalence is going up at the same time that people are getting more sedentary.”

Dr. Felson agrees physical activity is part of the picture, but cautions that physical activity has lots of complicated effects on knee OA. “We don’t know anything about the different levels or types of physical activity in these earlier populations,” he says. “We know individuals in the early industrial populations were often manual laborers and not recreational athletes and that manual laborers get more knee OA than people who are sedentary. But that is probably due to injuries they sustain at work, and that joint injury becomes knee OA later.”

Leigh F. Callahan, PhD, the Mary Link Briggs Distinguished Professor of Medicine, associate director at the Thurston Arthritis Research Center, and director of the Osteoarthritis Action Alliance at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, wrote an editorial looking at research on physical activity and osteoarthritis.4 The article emphasized the limited evidence to date on the preventive effects of physical activity on knee OA. “Currently, there are no conclusive data one way or another regarding increased physical activity being protective for OA,” she says.

However, Dr. Callahan urges rheumatologists to encourage physical activity for their patients.

The ACR published recommendations in 2012 for healthcare providers on counseling patients with arthritis on physical activity.5 Strong recommendations for patients with knee OA included:

- Participation in cardiovascular (aerobic) and/or resistance land-based exercise;

- Participation in aquatic exercise; and

- Weight loss (for overweight patients).

“Although the evidence supporting the use of physical activity for primary prevention of OA is not established, the evidence is solid that once someone has OA, physical activity has positive benefits,” Dr. Callahan says. “There is also overwhelming evidence that physical activity is good for overall health, and the evidence to date appears to indicate it does not cause OA, so appropriate activity should be recommended.”

Is Knee OA Preventable?

According to Dr. Wallace, thinking about physical activity as a potential risk factor suggests knee OA may be preventable. “From a clinical perspective, the real message is that the disease does seem to be more preventable than clinicians commonly acknowledge,” he says. “To develop robust preventative strategies, however, we have to start exploring different candidates for what the causes are for this disease.”

Dr. Felson agrees. “I’d say weight is part of the picture, and physical activity is part of the picture, and probably other factors that we have not well identified are part of the picture, too.” He thinks diet is one of those factors.

We need a better understanding of all the risk factors that may make knee OA a preventable disease. Looking back to earlier times to track disease prevalence is one way in which the risk factors may emerge, drawing from a better understanding of the conditions from which humans evolve and adapt to their changing environments.

Mary Beth Nierengarten is a freelance medical journalist based in Minneapolis.

References

- Murray CJ, Vos T, Lozano R, et al. Disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) for 291 diseases and injuries in 21 regions, 1990–2010: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet. 2012 Dec 15;380(9859):2197–2223.

- Deshpande BR, Katz JN, Solomon DH, et al. The number of persons with symptomatic knee osteoarthritis in the United States: Impact of race/ethnicity, age, sex, and obesity. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2016 Dec;68(12):1743–1750.

- Wallace IJ, Worthington S, Felson DT, et al. Knee osteoarthritis has doubled in prevalence since the mid-20th century. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2017 Aug 29;114(35):9332–9336.

- Callahan LF, Ambrose KR. Physical activity and osteoarthritis – considerations at the population and clinical level. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2015 Jan;23(1):31–33.

- Hochberg MC, Altman RD, April KT, et al. American College of Rheumatology 2012 recommendations for the use of nonpharmacologic and pharmacologic therapies in osteoarthritis of the hand, hip, and knee. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2012;64(4):465–474.