Although the true cause of systemic sclerosis (SSc), or scleroderma, remains unknown, researchers have made progress in detecting the autoimmune disease’s early presence. Beyond the physiological signs of Raynaud’s phenomenon, a capillaroscopy can detect alterations in microcirculation and lab tests can confirm the presence of telltale autoantibodies, such as anti-topoisomerase 1, anti-centromere and anti-RNA polymerase III, in serum.

Later symptoms may include vascular abnormalities with progressing fibrosis in the upper and lower gastrointestinal tract, kidneys and lungs.

“When the disease progresses, you can get the classical tissue involvement and symptoms beyond skin involvement,” says Maurizio Cutolo, MD, professor of rheumatology and internal medicine and director of research laboratories in the Academic Division of Clinical Rheumatology at the University of Genova, Italy. “But this is a story of cells that precede these changes.”

Researchers would dearly love to clarify the identities and alterations occurring early on in these cells. Most studies, though, haven’t examined the characteristics of immune cells past the involvement of B lymphocytes. Of those that have, many suggest that SSc monocytes and macrophages display a phenotype most closely associated with the anti-inflammatory M2 activation state.

Two recent studies in the Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases, including one by Dr. Cutolo’s research group, used different flow cytometry methods to take a much closer look. Their joint conclusion is that from the perspective of macrophage polarization, the SSc picture may be far more complicated than previously assumed.1,2 In fact, they suggest SSc cells may be much better characterized as a hybrid between the M2 and pro-inflammatory M1 polarization states.

Taking a Closer Look

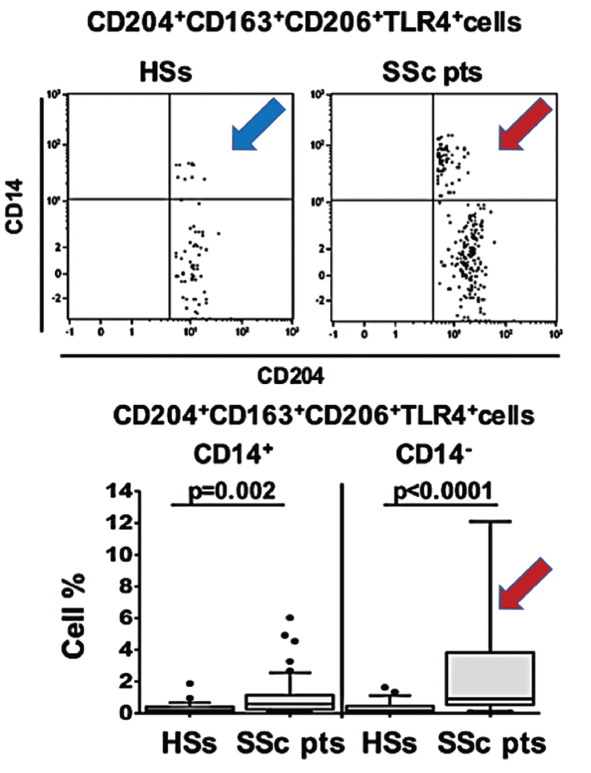

(click for larger image) Figure 1. In this figure, arrows show the increased population of blood circulating hybrid M1/M2 macrophages in scleroderma patients (red SSc) compared with healthy matched subjects (blue HSs).

As progenitor cells, circulating monocytes change in response to physical contact with other cells and signals from cytokines, growth factors and other soluble mediators in the microenvironment. When they differentiate into macrophages, the cells can be pulled toward the M1 activation state typical of immune defense and rheumatoid arthritis, or the M2 state more characteristic of wound healing, immune suppression, fibrosis and cancer growth and proliferation.

Polarization toward M1 or M2 can be identified via the expression levels of associated cell surface markers. The new studies suggest these blood-based biomarkers could help define the disease state. In addition, the high concentrations of hybrid cells circulating in the blood prior to their homing and specialization in body tissues might offer a promising target for early treatment.

“The emerging picture is that now we are investigating the role of not just B cells, but also the monocytes and macrophages in systemic sclerosis,” Dr. Cutolo says. “Now. we know they play an important role as cells involved in the fibrotic process.”

Dr. Cutolo emphasizes that such potential applications should be verified. Even so, he notes a subsequent study by his group suggested systemic sclerosis patients with interstitial lung disease have high concentrations of the M1/M2 hybrid monocyte/macrophage population as well.3

Collectively, Dr. Cutolo says, the research points toward a better way to characterize SSc patients, particularly when the disease involves the lungs. Beyond their utility as biomarkers of disease, the cell surface markers could be further examined for their role in pathogenesis. “So we have in our hands a lot of work to do, but they are very promising results, very interesting results,” he says.

Patricia Pioli, PhD, an assistant professor of microbiology and immunology at Dartmouth University who wasn’t involved in either study, agrees the research represents a big step forward in characterizing SSc. “These studies are really important in that they’re the first time, really, that people are looking at immune cells—macrophages and monocytes—in the context of the disease and trying to characterize them on some level beyond saying that they’re there,” she says.

The take-home message, Dr. Pioli says, is that there’s nothing uniform about the mix of activated macrophages in the disease. “Data from our lab in this regard also indicate that in the context of scleroderma, macrophages are not uniformly conforming to this either M1 or M2 activation profile,” she says. Therefore, rheumatologists should take a closer look at these peripheral blood cell populations and not just fibroblasts.

Study Details

Dr. Cutolo says other clinicians could readily adopt his study’s relatively straightforward cell characterization method. For the flow cytometry analysis, he and colleagues assessed 58 consecutive SSc patients and 27 age- and gender-matched healthy controls. The researchers collected peripheral blood from each study subject and used anti-CD14 and anti-CD45 antibodies to separate out the monocyte/macrophage lineage. Their analysis then used the CD163, CD204 and CD206 cell surface receptors as M2 phenotypic markers and the CD80, CD86, toll-like receptor (TLR) 2 and TLR-4 receptors for the M1 phenotype.

The macrophage phenotype results, which report the target cells as a percentage of the total number of circulating leukocytes, supported past associations between SSc patients and the M2 phenotype. Even so, they more clearly pointed to an association between the disease and a mix of cells expressing both M1 and M2 surface markers. By contrast, the analysis revealed no difference in the percentage of circulating M1 cells between the SSc patients and healthy controls.

The second study, led by Alain Lescoat, MD, Department of Internal Medicine at Rennes University Hospital in Rennes, France, took a different approach. Instead of circulating monocytes and macrophages, the researchers used macrophage-colony stimulating factor (M-CSF) to differentiate resting blood monocyte-derived macrophages (MDM) from a smaller cohort of SSc patients and matched controls. The group’s flow cytometry approach measured the mean of fluorescence intensity (MFI) ratio for cells expressing a slightly different mix of six polarization markers: CD163, CD204, CD206 and CD200R1 for M2 macrophages; and CD80 and CD169 for M1 macrophages.

Again, the results revealed a mixed M1/M2 signature for macrophages in the SSc patients. Despite the potential limitations of the small sample size, the authors wrote that they agreed with the suggestion by Dr. Cutolo’s research group to “think outside the box: beyond the dichotomous M1/M2 paradigm, using new phenotyping approaches may offer a more encompassing vision of macrophages in SSc.”

Dr. Cutolo says he was “very happy” to see the results of Dr. Lescoat’s study reinforce his own group’s findings.

In effect, Dr. Pioli says, the similar discoveries could open the door to additional prognostic and therapeutic markers. The relative expression levels of surface markers associated with M1 or M2, she agrees, may yield a more useful indication of how the disease is progressing and responding to interventions. “I think that looking at different levels of expression of these markers might be useful therapeutically if we can figure out interventions that are associated with down-regulation of some of these monocytes and macrophages that are potentially mediating fibrotic activation in the disease,” she says.

The emerging data may aid a closer examination of the underlying pathways as well, Dr. Pioli says. “The value is that once we figure out which cells these are that are potentially being pathogenic, we can then figure out what they’re making that’s inducing the fibroblast to become activated. Then we can really begin to discern some of the molecular mechanisms behind the way they’re actually inducing fibrosis in the disease.”

Next Steps

To further understand the respective roles of the macrophage cells, Dr. Cutolo says his group is conducting follow-up studies on rheumatoid arthritis characterized by the prevalence of pro-inflammatory M1 cells.

“We would like to try to reduce the M1 polarization and possibly increase the M2 polarization,” he says. The work may help reveal the differing M1-M2 balance between the pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokines in both diseases.

The CD86 marker, which is more closely associated with M1 cells but also up-regulated in M2 cells, for example, has been linked to both rheumatoid arthritis and systemic sclerosis macrophages. A CD86 blocker consisting of the fusion protein CTLA4-Ig (abatacept) has been a classical target for rheumatoid arthritis therapy. In a recent ACR presentation, Dr. Cutolo’s group suggests the biologic drug may benefit systemic sclerosis patients as well.

Combination therapies often include immune suppressors such as low-dose methotrexate or rituximab to deplete the C19 B lymphocytes that produce disease-promoting autoantibodies. Vasodilators plus vasoconstrictor inhibitors (such as endothelin-1 receptor blockers) can help promote blood flow and drug diffusion into tissues.

Researchers have long known that glucocorticoids can induce expression of the CD163 marker. In their study on lung involvement, Dr. Cutolo and colleagues analyzed the patients’ treatment regimens and noted that glucocorticoid use increased M2 polarization.

“This is probably one of the reasons why we don’t use glucocorticoids in systemic sclerosis too much—especially in high doses for overt disease—because it may induce a worsening of the disease,” Dr. Cutolo says.

He also says rheumatologists don’t yet know how other therapies in the existing and developing arsenal may alter the percentages of circulating macrophages, however. “So we have to treat patients with different drugs and we will see what happens.”4

Dr. Pioli cautions that it will be important to verify the study results with data from tissue macrophages, in part because the activation of macrophages is influenced by their local microenvironment. Researchers know that macrophages in different anatomical contexts, even within the same person, can have different activation profiles.

The low recovery rate of macrophages from human skin, she concedes, can present a major challenge for conducting functional studies. “But I think complementing these data with things like single-cell sequence data from primary tissue macrophages will be really important,” says Dr. Pioli. “And we can certainly use these peripheral blood cells as models based on what we know about their activation.”

If verified, the resulting signature of up-regulated markers could provide a better indicator of active systemic sclerosis, Dr. Pioli says. “I think it will be important for things like sub-setting patients, and down the line for potentially devising differential therapeutics for different patients based on their gene expression profile of the macrophages.”

Those goals are likely to be aided by a growing pool of macrophage cell surface markers. “I think that there are many, many more. This is really just scratching the surface,” Dr. Pioli says. “We can get a much more defined picture, I think, because this is just a very general survey, but I think it’s important because nobody’s done it.”

Bryn Nelson, PhD, is a medical journalist based in Seattle.

References

- 1. Soldano S, Trombetta AC, Contini P, et al. Increase in circulating cells coexpressing M1 and M2 macrophage surface markers in patients with systemic sclerosis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2018 July 16. [Epub ahead of print]

- 2. Lescoat A, Ballerie A, Jouneau S, et al. M1/M2 polarisation state of M-CSF blood-derived macrophages in systemic sclerosis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2018 Sep 29. [Epub ahead of print]

- 3. Trombetta AC, Soldano S, Contini P, et al. A circulating cell population showing both M1 and M2 monocyte/macrophage surface markers characterizes systemic sclerosis patients with lung involvement. Respir Res. 2018;19(1):186.

- 4. Cutolo M, Trombetta AC, Soldano S. Monocyte and macrophage phenotypes: a look beyond systemic sclerosis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2018 Sep 29. [Epub ahead of print]