Artemida-psy / shutterstock.com

Living like a king has its price. And while kings and queens are primarily something of yesteryear, the vast majority of those living in reasonably wealthy nations can now live like kings. Now, back to that price.

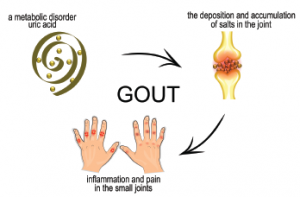

Gout, once known as the disease of kings, has been around at least since the time of the Egyptians.1 It is now the most common form of inflammatory arthritis worldwide, and its prevalence is on the rise around the globe.2

Hyperuricemia, an excess of uric acid in the blood (upper limit of normal 6.8 mg/dL), is an indicator of gout. Although the level of uric acid can be changed, researchers need reliable information on how many cases of hyperuricemia are preventable through risk factor modification.

A study published in Arthritis & Rheumatology, “Population Impact Attributable to Modifiable Risk Factors for Hyperuricemia,” studied the very real problem of how to prevent hyperuricemia and how much can actually be prevented.3

Diet vs. Genetics

Lead author Hyon K. Choi, MD, DrPH, is professor of medicine in the Division of Rheumatology, Allergy and Immunology, Massachusetts General Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston. “Recent research stands at odds with the traditional thinking regarding diet and genetics as related to increased serum urate levels [gout’s precursor],” he says. “This work has left many with the impression that there is nearly no role for diet as compared to genetics in gout. One particular study, which utilized the erroneous statistical measurement of ‘variance explained,’ examined how much variance in uric acid level is explained by diet.

“At face value the name sounds reasonable,” Dr. Choi continues. “However, the problem is that the variance only works when the exposure of interest is in the middle ground (e.g., 40% of the population is ‘exposed’). But when it is 85% or higher who have a poor diet (the U.S. population), then virtually everyone is ‘exposed.’ It is rather like the cause of a certain condition is invisible when it is ubiquitous. If everyone has it, then you can’t see it because the difference isn’t apparent. … So there is hardly any variance being explained.”

A Reliable Model

Using an approach proved successful in estimating the impact of lifestyle factors on myocardial infarction, diabetes and hypertension, among other conditions, Dr. Choi and his colleagues determined the population-attributable risk (PAR) for obesity, alcohol intake, diet and diuretic use.

“We took data on 14,624 adults from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey III, determined food intakes over the preceding month and developed a DASH [Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension] score based on items that are emphasized or minimized in the DASH diet (i.e., high intake of fruits, vegetables, nuts and legumes, low-fat dairy products and whole grains, and low intake of sodium, sweetened beverages and red and processed meats),” says Dr. Choi. “We calculated the PAR according to non-adherence to a DASH-style diet, body mass index [BMI], alcohol intake and diuretic use.

“Our study was able to ask, for example, ‘What is the proportion of XYZ that would disappear if you eliminate alcohol?’ This approach [i.e., PAR] takes into account how common those factors are.

“Our findings suggest that BMI strongly elevates uric acid levels at the population level. If you shed pounds, you shed uric acid. In fact, individuals who undergo bariatric surgery can essentially be cured of hyperuricemia. If everyone were to attain a normal, healthy weight (i.e., a BMI of less than 25), then 44% of hyperuricemia would disappear. Theoretically, that tells us how much BMI is responsible for this condition in the general population.”

Dr. Choi continues, “with regard to diet, [DASH] compliance is typically poor; however, if everyone is fully compliant, then more than 40% of hyperuricemia would disappear. As you might imagine, that is too stringent and, in fact, unattainable. We aimed for less than half compliance and found that if 40% are compliant, then 9% of hyperuricemia would be eliminated.

“Now to alcohol,” states Dr. Choi. “If there is no alcohol use, then 8% of hyperuricemia is explained. Diuretic use explained 12% of hyperuricemia.”

Unfortunately for researchers and clinicians alike, how people measure diet and alcohol consumption lacks precision. Asking people how much they eat and drink doesn’t result in accurate answers (unlike measuring genetic exposures). “Thus, we suspect the effects of diet and alcohol are higher than calculated,” says Dr. Choi.

Plan of Action?

Transforming research into a clinical plan of action is a thorny issue, Dr. Choi notes, because measuring “the consumption of food and alcohol is multifaceted. Promoting individual behavior changes must be done on the private and public fronts simultaneously. We need broader policy changes targeting sugary drinks, labeling reforms, federal nutrition programs addressing obesity and more. It is important to know that 44% of hyperuricemia was coming from obesity, but we have to look more closely at what is causing obesity. For example, we will likely have to invest more in behavioral and psychological interventions for obesity.”

Concerned that prior research has led patients to think their food and alcohol choices are irrelevant, Dr. Choi states, “It is not helpful if researchers take a misguided approach to this. The public puts its trust in us, and we must have what it takes to get it right. We cannot just blame genetics and close the book on hyperuricemia. That would be equivalent to blaming genetics entirely for the current obesity epidemic and recommending nothing about diet and exercise.”

Limitations

“Of course, our study contained limitations, namely that the measurement error for diet and alcohol underestimates the impact of these variables,” says Dr. Choi. “Unfortunately, that is the nature of this type of study. There is just no way to accurately assess how much food and alcohol someone is consuming over an extended period of time—especially because people tend to report consuming less alcohol than they actually imbibe.”

He says, “Going forward I would like to see more high-level longitudinal, prospective studies that measure exposures before endpoints of interest, particularly regarding the risk of gout.”

With one in five people having a high uric acid level, this research has the potential for a widespread impact.4

Elizabeth Hofheinz, MPH, MEd, is a freelance medical editor and writer based in the greater New Orleans area.

References

- Richette P, Bardin T. Gout. Lancet. 2010 Jan 23;375(9711):318–328.

- Kuo C-F, Grainge MJ, Zhang W, Doherty M. Global epidemiology of gout: Prevalence, incidence and risk factors. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2015 Nov;11(11):649–662.

- Choi HK, McCormick N, Lu N, et al. Population impact attributable to modifiable risk factors for hyperuricemia. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2020 Jan;72(1):157–165.

- High uric acid level: Definition. Mayo Clinic.