Angioimmunoblastic T cell lymphoma (AITL) is an aggressive, peripheral T cell, non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma with an incidence of 0.05 cases per 100,000 person-years in the U.S., and it typically manifests in adults older than 60 years.1,2

AITL was previously known as angioimmunoblastic lymphadenopathy with dysproteinemia, immunoblastic lymphadenopathy or lymphogranulomatosis X, due to the hypothesis that the disease was an immune dysregulation of both B and T cells.1,3 Subsequent advancements in genomic studies uncovered its true pathogenesis as a primary T cell malignancy. AITL has a multitude of clinical presentations with notable systemic B symptoms: splenomegaly, hepatomegaly, polyarthritis and generalized lymphadenopathy.

In this article, we present the case of a patient diagnosed with AITL and referred to a rheumatologist for the management of rheumatoid factor-positive polyarthritis, suspicious for rheumatoid arthritis (RA).

The Case

A 71-year-old white man was referred to a community hospital rheumatology clinic in September 2017 for evaluation of a month-long history of generalized arthralgias. A month earlier, the patient had been evaluated by his primary care provider in a routine checkup. A pneumococcal vaccination was administered, and within 24 hours the patient’s arthralgias began. He also reported worsening malaise, fatigue, nausea and subjective fevers that had occurred over the preceding several weeks. Concerned for infection, his doctor hospitalized the patient briefly. After tests for infection proved negative, the patient was started on prednisone at 20 mg daily, his symptoms improved substantially, and he was discharged home.

During the patient’s initial workup in the rheumatology clinic, he was tested for rheumatoid factor, which was positive at 47 IU/mL (normal <15). Anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide (anti-CCP), IgG, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, C-reactive protein and hepatitis B and C screening tests were normal or negative.

Radiographs of the hands taken in September 2017 demonstrated no erosions. His prednisone dosage was decreased, but the decrease to 15 mg daily led to a substantial worsening of his symptoms. Methotrexate 15 mg once a week was then added to his prednisone (held at 20 mg daily), but again when prednisone was tapered, his symptoms quickly returned.

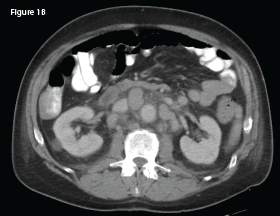

Computed tomography (CT) imaging of his chest, abdomen and pelvis in late 2017, pursued out of concern he had an illness other than RA (see Figure 1A), was unremarkable.

Sulfasalazine and hydroxychloroquine were added, but his symptoms persisted. Ultimately, tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitors were added, but tapering of other medications, specifically prednisone, led to the return of symptoms.

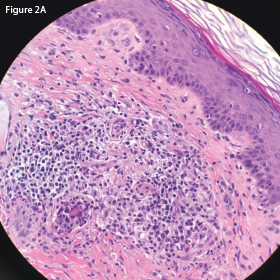

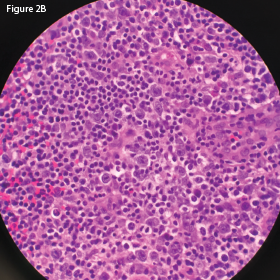

In May 2018, the patient was evaluated in the emergency department of the same hospital for possible diverticulitis. CT scans demonstrated bulky retroperitoneal and abdominal lymphadenopathy (see Figure 1B, below). He was hospitalized, and a biopsy of a retroperitoneal lymph node revealed AITL. Bone marrow biopsy showed similar involvement. Histologic findings demonstrated a marked proliferation of small- to medium-sized lymphocytes with clear cytoplasm, in addition to increased arborizing high endothelial venules (see Figures 2A–2B8).

This CT of the abdomen from September 2017 demonstrates no intra-abdominal abnormalities or lymphadenopathy.

This CT of the abdomen from May 2018 demonstrates interval development of intra-abdominal lymphadenopathy (indicated by the white arrow).

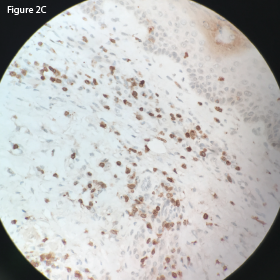

Immunohistochemistry staining demonstrated a diffuse predominance of CD3 positive T cells (see Figure 2C, p. 28). Flow cytometry was notable for an expanded population of CD3-positive T cells.

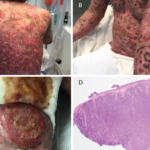

The patient was evaluated by oncology and treated with CHOEP (cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, etoposide, vincristine and prednisone). Despite treatment, he experienced a rapid decline in his health, with cutaneous metastases developing in late 2018 and recurrent hypercalcemia in early to mid-2019. He succumbed to his AITL in mid-2019.

Discussion

AITL is a rare disease that accounts for 1–2% of all non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas and about one in five cases of peripheral T cell lymphomas.4 First described in 1974, the disease was named angioimmunoblastic lymphadenopathy with dysproteinemia.2,4,5 Patients classically presents with B symptoms, as described above, or with a rash (observed in 20–50%), which may include urticarial lesions and nodular tumors.4

AITL leads to three pathologically characteristic histological and architectural changes in lymph nodes: extensive alteration of the nodal architecture, abundance of small vessels and polyclonal proliferation of immune reactive cells.6

Once considered an aggressive neoplasia that derived from an abnormal immune reaction, genomic studies have since demonstrated AITL to be a clonal rearrangement of T cell receptor genes due to acquired driver genes.2,7 Follicular T helper cells are the main subset implicated in the pathogenesis of AITL. This subset of T cells resides within the follicles, and their main role is to support B cell survival, proliferation, maturation and migration.3

Several genetic changes have been implicated in the neoplastic transition of T follicular helper cells, such as the G17V mutation of Ras homolog family member A.3 Although this mutation has also been identified in other malignancies, such as diffuse gastric carcinoma and Burkitt lymphoma, it may serve as a non-invasive diagnostic test for AITL in the future.1,3

Given the immune-activating effects of AITL, the production of detectable levels of rheumatoid factor and the anti-smooth muscle antibody may result in positive autoantibody tests.3

This hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) stain of the retroperitoneal lymph node at 40x magnification demonstrates atypical lymphocytes and numerous plasma cells.

This H&E stain of the retroperitoneal lymph node at

60x magnification demonstrates enlarged and

atypical lymphocytes.

This CD3 stain at 40x magnification of the retroperitoneal lymph node demonstrates

diffuse uptake.

A case report in 1982 by Meyers et al. discussed a patient who presented with generalized arthralgias and failure to respond to conventional therapy for RA who was subsequently diagnosed with AITL.5

Another case report in 1986 by Bignon et al. reported the development of AITL in a patient with sicca symptoms.8 AITL has been reported to arise from extra-nodal lymphoid tissue, and in the case reported by Bignon et al., lymphoproliferation was observed involving the lip of the patient with the immunohistological comparison similar to the primary site of the kidney.9-11

Pathak et al. reported a case of AITL in association with Guillain-Barré syndrome diagnosed after rapid onset of ascending lower extremity paralysis.12 In this case the patient developed lymphadenopathy after being discharged, and immunohistological biopsy later revealed the diagnosis.12

The correlation of malignancy with rheumatic illness is a complex, fascinating aspect of immunology. The arthritis associated with AITL can present very similarly to that of RA, with symmetric involvement of proximal joints. It is usually non-erosive, seronegative and non-deforming, but is typically associated with constitutional symptoms and elevated markers of inflammation.

Although [the G17V mutation of Ras homolog family member A] mutation has also been identified in other malignancies, … it may serve as a non-invasive diagnostic test for AITL in the future.

The arthritis of AITL responds well to low to moderate prednisone doses, but remains unresponsive to disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs and biologic response modifiers. Our patient demonstrated this with multiple relapses after his prednisone dose was decreased.

This case highlights several diagnostic and therapeutic challenges. First, not all positive rheumatoid factor tests are associated with RA.

Second, a patient’s difficulty tolerating a taper in prednisone, especially when used in conjunction with other disease-modifying drugs or biologic response modifiers, should prompt the rheumatologist to consider an alternative etiology for arthritis.

Finally, failure of RA to respond to triple or even quadruple therapy should also prompt concern for an alternative etiology.

Francis Essien, DO, is an internal medicine resident at Keesler Medical Center, Keesler Air Force Base, Miss.

Matthew B. Carroll, MD, FACP, FACR, is a rheumatologist with Singing River Health System, Ocean Springs, Miss.

References

- Lunning MA, Vose JM. Angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma: The many-faced lymphoma. Blood. 2017 Mar 2;129(9):1095–1102.

- Mangana J, Guenova E, Kerl K, et al. Angioimmunoblastic T-Cell lymphoma mimicking drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS syndrome). Case Rep Dermatology. 2017 Mar 21;9(1):74–79.

- Fukumoto K, Nguyen TB, Chiba S, Sakata-Yanagimoto M. Review of the biologic and clinical significance of genetic mutations in angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma. Cancer Sci. 2018 Mar;109(3):490–496.

- Yachoui R, Farooq N, Amos JV, Shaw GR. Angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma with polyarthritis resembling rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Med Res. 2016 Dec;14(3–4):159–162.

- Meyers OL, Klemp P. Lymph node enlargement in rheumatoid arthritis. A case of angio-immunoblastic lymphadenopathy. S Afr Med J. 1982 Dec 25;62(27):1038–1039.

- Mukherjee T, Dutta R, Pramanik S. Aggressive angioimmunoblastic T cell lymphomas (AITL) with soft tissue extranodal mass varied histopathological patterns with peripheral blood, bone marrow, and splenic involvement and review of literature. Indian J Surg Oncol. 2018 Mar;9(1):11–14.

- Ozoran K, Turgay M, Kinikli G, et al. Angioimmunoblastic lymphadenopathy with dysproteinemia arising in a patient with rheumatoid arthritis. Scand J Rheumatol. 1995;24(1):58–60.

- Bignon Y, Mercier A, Dubost J, Ristori J, et al. Angioimmunoblastic lymphadenopathy with dysproteinaemia (AILD) and sicca syndrome. Ann Rheum Dis. 1986 Jun;45(6):519–522.

- Hashefi M, McHugh TR, Smith GP, et al. Seropositive rheumatoid arthritis with dermatomyositis sine myositis, angioimmunoblastic lymphadenopathy with dysproteinemia-type T cell lymphoma, and B cell lymphoma of the oropharynx. J Rheumatol. 2000 Apr;27(4):1087–1090.

- Kojima M, Motoori T, Hosomura Y, et al. Atypical lymphoplasmacytic and immunoblastic proliferation from rheumatoid arthritis: A case report. Pathol Res Pract. 2006;202(1):51–54.

- Pierce DA, Stern R, Jaffe R, et al. Immunoblastic sarcoma with features of Sjögren’s syndrome and systemic lupus erythematosus in a patient with immunoblastic lymphadenopathy. Arthritis Rheum. 1979 Aug;22(8):911–916.

- Pathak P, Perimbeti S, Ames A, Moskowitz A. Guillain Barré syndrome heralding the diagnosis of angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma. Leuk Lymphoma. 2019 Jul;60(7):1835–1838.