Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) have received much negative attention during the last few years—particularly because of concerns about cardiovascular side effects when they are used to treat RA and osteoarthritis. These concerns contributed to Merck’s decision to withdraw the COX-2 inhibitor rofecoxib from the market in 2004, followed a year later by Pfizer’s withdrawal of a similar medication, valdecoxib. The controversy again heated up early in 2007 when the American Heart Association (AHA) issued a Scientific Statement containing guidelines for the use of all NSAIDs in those with cardiovascular problems or risk factors for ischemic heart disease.1

What the AHA Statement Says

“Our Scientific Statement was a review of the evidence suggesting that NSAIDs may impose an increased risk of heart attack, stroke, and death in patients with known heart disease or who are at risk for ischemic heart disease,” says Elliott M. Antman, MD, director of the coronary care unit at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston and lead author of the article. “Although disease-modifying therapy is very much in the front line of treatment to decrease inflammation and joint damage, at some point consideration will be given to relieving pain. The statement indicates the level of risk as perceived by the American Heart Association for the various drugs and recommends a five-step approach starting with those medications seen as having less cardiovascular risk and moving progressively toward those with higher cardiovascular risks.”

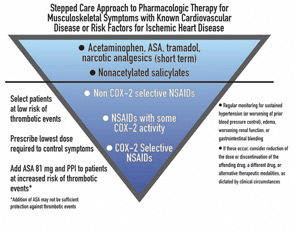

While stressing that they are not trying to overstep the domain of rheumatologists, the authors suggest what they called a “stepped care approach” starting off with acetaminophen, acetylsalicylic acid (ASA), and narcotic analgesics; followed by nonacetylated salicylates; then non COX-2 selective medications; NSAIDs with some COX-2 activity; and reserving COX-2 selective drugs for a last resort. (See Figure 1)

“[The COX-2 inhibitors] are a class of drugs that are not necessarily more effective than traditional drugs, are associated with an increased cardiovascular risk, and do not offer as much gastrointestinal tract protection as originally thought,” says Dr. Antman. “Given all of that, the Scientific Statement says that in patients with heart disease or risk for ischemic heart disease, they should be the last group of medications tried.”

Rheumatologists Take a Different View

There was a consensus among the rheumatologists interviewed for this article that the AHA Statement was oversimplified and only addressed the cardiovascular side effects while ignoring concerns about other types of adverse effects.

“Only discussing safety is a bit unrealistic,” says David G. Borenstein, MD, a rheumatologist with Arthritis and Rheumatism Associates in Washington, D.C., and an editorial board member of The Rheumatologist. “I think one needs to be more sophisticated in regard to the kinds of patients being seen when making a choice as to what is appropriate therapy.”

Tailoring the entire therapy to the individual is key to proper use of all types of NSAIDs, according to the experts. A careful history and physical of both the patient and family to look for heart disease or gastrointestinal concerns is an important first step. The amount of inflammation manifest by the patient is another consideration, as is age and the severity and type of pain. Then decisions can be made on which medication or additional therapies should be prescribed.

“The rheumatologist knows that all NSAIDs can cause many kinds of side effects and they must be used at the lowest possible dose for the shortest possible amount of time,” says Steven B. Abramson, MD, professor of medicine (rheumatology) and pathology at the New York University Medical Center in New York and a member of the ACR Drug Safety Committee.

These side effects are not immutable. Just as proton pump inhibitors can limit gastrointestinal bleeding, some of the cardiovascular risk factors can be mitigated. For example, weight loss and diet changes can lower high blood pressure and diabetes—two major cardiovascular risk factors. Calcium channel-blocking drugs or cholesterol lowering medications may be another consideration.

Limited Options Complicate Therapy

Indeed, with the withdrawal of rofecobix and valdecoxib followed by the recent decision by the Food and Drug Administration to deny marketing approval for the COX-2 inhibitor etoricoxib, the number of options available to the physician has diminished. This may mean the use of multiple medications to address the gastrointestinal and cardiovascular side effects.

“I think that the preference has been to use non-drug means to limit side effects,” says Dr. Borenstein. “What might be new now for clinicians is the fewer choices we will have and with only ‘older drugs’ to select, we will have to make them work like we did a decade ago. The result will be using what is necessary to limit, reverse, or minimize any ill effects from the drugs we need to use to get the patients better.”

As with most other medications, NSAIDs are not something that can be prescribed and then forgotten about. Frequent follow-up with the patient to assess changes in blood pressure, swelling of the extremities, and possible gastrointestinal problems needs to be accomplished. Instructing the patient to recognize these side effects and report them immediately to their physician is also important.

It is important to review with your patients the reasons you think the prescribed medication is the best choice. The controversy over NSAID safety—especially that of COX-2 inhibitors—has changed the dynamic between the doctor and the patient.

“Before the concerns were raised, most of my patients wanted something that would ease their pain,” said Dr. Borenstein. “Their sensitivity level is such that safety now is a greater concern than efficacy in regard to their problem. This idea of having a safe medication and then seeing if it works is putting the cart before the horse.”

Careful patient education is one way to alleviate patients’ safety concerns. “What I try to do when I give any drug is talk about what kinds of side effects they can expect,” says Leslie J. Crofford, MD, chief of the division of rheumatology at the University of Kentucky College of Medicine in Lexington. “For non-specific and COX-2–specific inhibitors, I mention that there might be a small increase in incidence of heart attacks. I also mention that the risk for gastrointestinal bleeding and other adverse events for some of these medications is much higher than the risk for heart attack depending on individual comorbidities. If they remain uncomfortable with a particular drug, you have to respect their wishes.”

Overall, the rheumatologist has to weigh the desirable and undesirable effects of the medication and decide what is best for that particular patient, according to those interviewed.

Rheumatologists recommend these sites for reliable patient-education materials:

ACR NSAIDs patient education fact sheet:

www.rheumatology.org/public/factsheets/nsaids.asp

Arthritis Today NSAIDs drug guide:

www.arthritis.org/arthritistoday/drugguide/about_nsaids.asp

Concerns with the Science

One of the concerns expressed by rheumatologists interviewed here is that the Circulation article takes a “tunnel view” of the situation by focusing on cardiovascular effects without weighing other concerns. For example, the use of narcotic analgesics raises concerns of its own, including constipation, dizziness, and falls in older patients.

Others question the science behind the AHA Statement. “There are two areas of misrepresentation that I see,” says Dr. Abramson. “There is no evidence, with the exception of high-dose naproxyn in a clinical-trial setting, that COX-2–specific inhibitors carry a greater cardiovascular risk than traditional NSAIDs, yet their algorithm suggests that they are safer than COX-2 inhibitors. They also suggest starting treatment with ASA, non-ASA, and opioids which is totally outrageous because there is no data to support it.”

Another concern is that “the statement does not take into account the differences between the musculoskeletal conditions for which these agents might be used or the diversity of biological effects of the COX-1– and COX-2–derived prostaglandins that may affect other organ systems,” says Dr. Crofford. “The way the statement was put together from a specific cardiovascular risk-focused perspective did not adequately capture the diversity of conditions [we see] that would need different types of therapy and also the diversity of personal risks seen in our patients.”

Bottom Line: Balance Benefit and Risk

Dr. Crofford suggests that physicians need to realistically evaluate drug risks in the specific patient before them.

“The bottom line is that there has to be a balance in the risk–benefit ratio, the patient has to be informed, and the physician has to be knowledgeable,” she says. “If these criteria are met, I am in favor of giving patients and physicians choices of drugs.”

Kurt Ullman is a freelance writer based in Indiana.

References:

- Antman EM, Bennet JS, Daughtery A, et al. Use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs: An update for clinicians: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2007;115:1634-1642.

- Callahan LF, Pincus T. Mortality in the rheumatic diseases. Arthritis Care Res. 1995;8:229-241.

Guidelines for the Perplexed, Or how I lost my poetic license but not my medical license

By David Fox, MD

Now, as you know, with the drug hydralazineSome cases of lupus are now and then seen. So should rheumatologists hold a convention To promulgate guidelines about hypertension?

Wait! Before you might answer, consider the statin, That cute little pill that will lower the fat in Your arteries cardiac—yet there’s a fuss all Because this same statin can inflame your muscle!

Would it therefore not be especially sensible, Indeed, one could even suggest, indispensable, To have ACR guidelines on lowering lipid? Or would this sort of venture instead be insipid?

Now here come our friends from American Heart, Eager, as always, to play a big part, In telling us all how we should treat arthritis, Rheumatoid, osteo-, even bursitis.1

Great experts are they as they quickly will tell us, And their wise advice now is designed to propel us To change how we treat the diseases rheumatic, To avoid any more cardiology static.

“It’s RA! Well, goodness, do not use an NSAID, Until you have tried heat and cold—even rest in bed. If you say ‘pretty please’ we’ll allow a naproxen, Even though those who get it might then need digoxin!

And narcotics—be sure that you use lots of those, To treat inflammation in fingers and toes. Reduction in swelling? The joints might not show it, But your patient will be too obtunded to know it!”

So how should we deal with this unsought advice? Should we fuss and protest or instead just make nice? Should our own guidelines undergo major revision, Or should we instead merely laugh in derision?

We might instead say, “Cardiology friends, It seems that our specialties could make amends, If you, notwithstanding the size of your fees, Acknowledged some limits of your expertise,

And saw that when treating arthritic disease Rheumatology input is critical, please!”

Dr. Fox is chief of rheumatology at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor.

ACR Speaks Out: Comments from the College

The AHA recently issued a position statement on the use of NSAIDs.1 While this statement provides a useful overview of the published studies relating to cardiovascular risk associated with both the selective and non-selective COX inhibitor NSAIDs, the position statement suggests a treatment strategy for arthritis pain that is not based on solid evidence or clinical judgment.

As the current president and members of the Drug Safety Committee of the ACR, we feel that the “stepped-care approach to management of musculoskeletal symptoms” in this article oversimplifies the management of patients with rheumatic diseases. In many acute and chronic musculoskeletal disorders, the pathophysiologic underpinnings are a direct result of inflammation. NSAIDs have been shown to specifically suppress the inflammatory process and provide excellent relief in many painful rheumatic conditions in both experimental and clinical studies. These agents improve symptoms and minimize tissue complications associated with progression of inflammatory processes.

Randomized placebo and active controlled clinical trials have established the efficacy of NSAIDs over and above many other analgesic agents. Moreover, to be effective in suppressing the inflammatory process, these NSAIDS need to be used in the pharmacologic doses and dosing duration found to suppress the COX mediated inflammatory process. RA, the spondyloarthropathies, psoriatic arthritis, and osteoarthritis have been shown to cause early death, chronic disability, and a significant negative effect on overall quality of life.2

While we appreciate the documented cardiovascular toxicity associated with selective and non-selective NSAIDs, the current AHA statement does not reflect the proven benefits of these agents in patients with arthritis and other chronic inflammatory conditions. Sufficient treatment options are critical for patients with arthritis. Just as collaborative treatment plans for a given patient result in improved care, we urge the cardiology community to engage their rheumatology colleagues in formulating optimal recommendations for the use of NSAIDs.

Neal S. Birnbaum, MD, ACR President Daniel J. Lovell, MD, MPH, and Daniel H. Solomon, MD, MPH, for the ACR Drug Safety Committee members