(Reuters Health)—Many doctors who serve on hospital panels overseeing the ethics and safety of human research trials have industry relationships that may compromise their objectivity, but reporting these conflicts has become more common over the past 10 years, according to a new study.

Physicians who serve on so-called institutional review boards (IRBs) may also be providing biotechnology, drug and device companies with services or expertise in return for payment.

“(IRBs) approve and oversee the studies which are often funded by pharmaceutical companies,” said lead author Eric G. Campbell of Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston. “People who serve on these committees may have financial relationships with companies whose research they oversee, and that has potential positive and potential negative consequences.”

Having a relationship with the company funding the research may mean you have more experience with the area of study and can be an expert judge of whether a study protocol is safe and ethical, but it could also bias your decision in favor of the company, Campbell told Reuters Health by phone.

“It’s important to disclose their relationships and also to not vote on protocols for which they have conflicts,” he said. “Universities have gotten much better at disclosing conflicts,” but many physicians still vote on protocols they have a relationship with, he said.

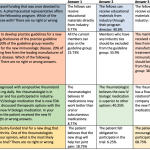

For the new study, researchers replicated a 2005 survey of IRB members, mailing surveys to 115 research-intensive medical schools and teaching hospitals. They received responses from 493 members in 2014, slightly more than had answered in 2005.

About a third of IRB members had some kind of industry relationship in 2005 and 2014, but the percentage who felt another member did not properly disclose their financial relationships in the past year decreased from 10.8 percent to 6.7 percent, the researchers reported in JAMA Internal Medicine.

More than half of physicians in 2014 said their institution had a formal written definition of a conflict of interest, compared to fewer than half of those who responded in 2005.

The percentage who felt another IRB member had presented a protocol in a biased manner because of their industry relationship decreased, as did the percentage who felt pressure to approve a protocol they felt was not ready.

But the percentage of members who voted on a study protocol with which they had a conflict of interest did not decrease significantly over time.

Academic medical centers could still improve how they clarify and publicize their conflict of interest policies, as many physicians are still in the dark about their institution’s policy, Campbell said.

Patients who enroll in clinical trials, whether they know it or not, need to be able to trust an IRB to make sure the trial is ethical and safe, he said.

“Clinical research is so important—there are so many serious diseases and health conditions that we must understand to improve the health of the public,” said Dr. Laura Weiss Roberts of Stanford University School of Medicine in California, who wrote a commentary on the new results. “For this reason, a strong IRB is really the ‘best friend’ to great clinical researchers.”

“Professionals should, in my view, engage in many different kinds of activities that make the best use of their expertise in society,” which generates potential conflicts, she told Reuters Health by email.

Conflicts of interest should not be misunderstood or vilified, she said.

“Some conflicts are incompatible with certain roles and activities, but many role conflicts and resulting conflicts of interest can be managed very effectively,” Roberts said.