The intersection of rheumatology and ophthalmology is one in which each specialist needs to truly work well with the other to ensure proper communication and patient care, according to James Rosenbaum, MD, an expert in both fields. Dr. Rosenbaum may be the only rheumatologist in charge of an ophthalmology department. As chair of the Division of Arthritis and Rheumatic Diseases, Oregon Health & Science University, and chief of ophthalmology at Legacy Devers Eye Institute, both in Portland, he understands what he calls the “lacunae in our information” for both fields.

The intersection of rheumatology and ophthalmology is one in which each specialist needs to truly work well with the other to ensure proper communication and patient care, according to James Rosenbaum, MD, an expert in both fields. Dr. Rosenbaum may be the only rheumatologist in charge of an ophthalmology department. As chair of the Division of Arthritis and Rheumatic Diseases, Oregon Health & Science University, and chief of ophthalmology at Legacy Devers Eye Institute, both in Portland, he understands what he calls the “lacunae in our information” for both fields.

“Ophthalmologists typically don’t know a lot of about immunosuppressive medication, and on the other hand, rheumatologists typically don’t know a lot about eye disease,” Dr. Rosenbaum says. “If two physicians are equally important in the management [of eye disease], I guess it becomes a little bit like two 5-year-olds sharing a toy. Who’s in charge? Who gets what when? Who gets credit? How do you divide the responsibility?”

The answer to each of these rhetorical questions is teamwork, Dr. Rosenbaum says. And although the mantra of teamwork is preached for all situations in which subspecialists co-manage patients, he suggests it is even more important for rheumatologists and ophthalmologists because their skill sets are often vastly different.

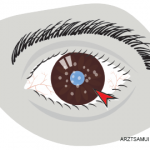

“The rheumatologist is impaired in the sense that he or she doesn’t have the instruments to look inside the eye and know whether there is ongoing inflammation,” Dr. Rosenbaum says. “The ophthalmologist is impaired only in the sense of [their] training and approach, so that systemic medications are usually a little bit intimidating.”

One reason for the lack of knowledge on rheumatologists’ part is the change over the past few decades in how physicians are taught to approach physical exams.

“When I started medical school, we had an ophthalmoscope, and we were taught to use the ophthalmoscope. And when we made rounds and worked up a patient in internal medicine, we would do an ophthalmic exam,” Dr. Rosenbaum says. “Now, if you have a patient in the hospital and you want to look for a sign called a ‘Roth spot’ or look in the back of the eye, it’s very hard to ask anyone on the hospital floor to find an ophthalmoscope. They just don’t exist anymore. As technology has gotten better, our imaging has gotten better, our ultrasound and radiology and all kinds of diagnostic tests have gotten better, [but] our skills with the physical exam have disappeared.”

Dr. Rosenbaum says that when his rheumatologist colleagues are evaluating patients with eye disease, they have two jobs: determine if the eye disease is related to a systemic problem and provide a risk–benefit analysis of potential therapies. Both need to be done in conjunction with an ophthalmologist, and both physicians should work to communicate in real time.

“It’s a difficult process, because first of all, the patient is a ping pong ball in the middle,” Dr. Rosenbaum says. “Let’s say that doctor to whom [the patient has] gone to is an ophthalmologist and the ophthalmologist says [to them], ‘Well, you have a serious problem, but before I do anything, you’ve got to see a rheumatologist, and it’s going to be six weeks before you get in.’ … We have to communicate.”

Language barrier: That communication extends to interpreting abbreviations associated with physical exams. In rheumatology, SLE stands for systemic lupus erythematosus. In ophthalmology, it stands for slit-lamp examination. In ophthalmology, RSVP stands for redness, sensitivity to light, vision change and pain or persistence in symptoms. A rheumatologist may read that abbreviation as simply an invitation to respond to a note left by a prior physician.

“It can get complicated,” Dr. Rosenbaum says.

An additional complication surfaced last summer for both specialties when the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved adalimumab to treat adults with non-infectious intermediate, posterior and panuveitis.1 (Note: Dr. Rosenbaum disclosed in an interview that he serves as an advisor to AbbVie Inc., the drug’s manufacturer.) The federal sign-off drew attention from rheumatologists because the treatment, which is common for rheumatoid arthritis, juvenile idiopathic arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, psoriatic arthritis and other conditions, had never before been approved for an ophthalmic disease. Dr. Rosenbaum says the drug can be valuable, but for patients with eye issues, it is the first non-corticosteroid therapy. In that vein, the FDA in 2014 allowed an orphan drug designation for treating certain forms of non-infectious uveitis.2

Before an ophthalmologist prescribes the drug to a rheumatic patient, Dr. Rosenbaum argues they should be in touch with that person’s rheumatologist—and vice versa.

“Ophthalmologists see patients with uveitis, but feel uncomfortable prescribing a drug, [such as] adalimumab. And rheumatologists should never prescribe adalimumab for uveitis on their own [without an ophthalmology consult] because a rheumatologist can’t gauge how active the inflammation is,” Dr. Rosenbaum says. “Again, both parties need each other, and it’s like a marriage.”

Richard Quinn is a freelance writer in New Jersey.

References

- AbbVie Inc. News release: AbbVie’s HUMIRA (adalimumab) receives U.S. Food and Drug Administration approval to treat adults with non-infectious intermediate, posterior and panuveitis. 2016 Jun 30.

- AbbVie Inc. News release: AbbVie receives orphan drug designation for Humira (adalimumab) from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for the investigational treatment of certain forms of non-infectious uveitis. 2014 May 20.