ACR Convergence 2020—In May 2020, the ACR published its updated guideline for the management of gout.1 It followed on the heels of a 2017 gout guideline published by the American College of Physicians.2 Although the guidelines provide similar recommendations on the treatment of acute gout, they differ importantly in the use of uric acid-lowering therapy for long-term management of gout. In a session titled Evidence-Based Guidance for Optimizing Gout Management, Robert Terkeltaub, MD, chief of rheumatology at the VA Medical Center San Diego, professor of medicine in the Division of Rheumatology, Allergy and Immunology at the University of California, San Diego, and president of the Gout, Hyperuricemia and Crystal-Associated Disease Network (G-CAN), discussed these differences and highlighted the evidence that continues to support the ACR recommendations on uric acid-lowering and treat-to-target strategies for managing chronic or tophaceous gout.

In a session titled Evidence-Based Guidance for Optimizing Gout Management, Robert Terkeltaub, MD, chief of rheumatology at the VA Medical Center San Diego, professor of medicine in the Division of Rheumatology, Allergy and Immunology at the University of California, San Diego, and president of the Gout, Hyperuricemia and Crystal-Associated Disease Network (G-CAN), discussed these differences and highlighted the evidence that continues to support the ACR recommendations on uric acid-lowering and treat-to-target strategies for managing chronic or tophaceous gout.

Calling the new evidence weighed by the 2020 ACR updated guidelines “robust,” Dr. Terkeltaub provided an assessment of the new data supporting the strong benefits of lowering uric acid levels on reducing joint structural effects and damage (e.g., synovitis and erosions), reducing the uric acid burden (e.g., uric crystal deposits in tissue) and managing symptoms (e.g., acute flares). “These are all significant and impactful benefits that justify a uric acid-lowering approach in more patients, as well as a treat-to-target strategy,” he said. Table 1 (below) highlights the results of the key evidence he discussed.

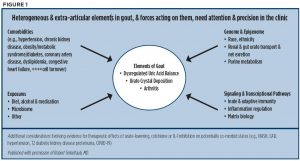

Some unknowns remain: One important question not addressed in the guideline is how to more quickly prevent or limit synovitis and joint damage, including erosions. Another is what the impact of achieving targeted uric acid levels is on the whole patient. Dr. Terkeltaub discussed remaining gaps in the clinical care of gout and emphasized the important role of pharmacogenetics to arrive at a more precise way to treat patients (see Table 2, bottom). He also provided a graphic showing the heterogenous elements of gout that need attention to provide more precise and personalized management of gout (see Figure 1).

Treat the Whole Person

Dr. Terkeltaub believes answers to these questions will be forthcoming, particularly given the work being done in providing good molecular pharmacogenomics. Citing the use of the HLA-B*5801 gene test to predict severe allopurinol hypersensitivity syndrome to identify patients to whom allopurinol should not be given, he underscored the growing interest in, and understanding of, the ABC transporter gene ABCG2 and whether it and its variant, Q141K ABCG2, may offer similar benefits for gout management.

An interesting factor, but one of as yet unknown clinical significance, is data showing that ABCG2 is inhibited by febuxostat, but not allopurinol, which, Dr. Terkeltaub noted, needs further study. Importantly, newly published results of the Febuxostat vs. Allopurinol Streamlined Trial (FAST) showed febuxostat to be non-inferior to allopurinol with regard to cardiovascular events and mortality.3 Commenting on the good retention of patients in this study, Dr. Terkeltaub said he expects the study to be reviewed by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, third-party payers and others to determine how these results will help inform clinicians when making a decision about which therapy to prescribe, particularly in patients with preexisting major cardiovascular disease. “I think it is a very dynamic issue,” he said.

Table 1: Updated Evidence from Key Trials

| Dalbeth et al. Arthritis & Rheumatology. 2017;69. | Febuxostat treat-to-target, uric acid-lowering therapy significantly reduces gout flares and MRI synovitis scores, especially at 1–2 years compared with placebo in early gout. |

| Doherty et al. Lancet. 2018;392. | A treat-to-target, urate-lowering strategy was applied in a nurse-led effort; compared with “usual gout treatment” in primary care, allopurinol 100 mg/d titrated to max 900 mg/d was effective in reducing the urate level burden and flares in most patients. Febuxostat 80–120 mg/d can be used as a backup or second-line therapy for most patients. |

| Ellman et al. Arthritis & Rheumatology. 2019;72. | Xanthine oxidase inhibitor treatment decreases urate crystal deposits in sample joints at 18 months’ follow-up. |

| Hammer HB, et al. Ann Rheum Dis. 2020;79. | Xanthine oxidase inhibitor treat-to-target rapidly improves cartilage surface crystal deposits as shown on ultrasound, with slower decreases in articular urate crystal tophaceous and tendon/enthesis aggregate deposits. |

| Dalbeth N, et al. Arthritis & Rheumatology. 2019;71. | Allopurinol uric acid-lowering, dose-escalation to treat to target limits joint erosion scores assessed by CT scan. |

Table 2: Key Gaps in Gout Care

| Question | Issues |

|---|---|

| What is the target? | Need to better refine serum urate target and anti-inflammation by addressing issues, such as how low, how quick and how long to target uric acid-lowering levels. |

| What is achieved by reaching the target? | Need to consider the impact of targeted uric acid-lowering therapy, as well as other therapies, such as colchicine and IL-1 beta inhibition, on the whole person. How do these therapies benefit patients with cardiovascular, renal or fatty liver disease, and affect mortality? |

| How should we treat hyperuricemia in patients with stage IV chronic kidney disease? | Inadequate evidence currently exists to guide this; need trials to answer this question. |

| What is the role and use of uricosurics, either alone or combined with xanthine oxidase inhibitor therapy? | Need to better understand when to use a uricosuric, particularly as monotherapy, and when to combine it with xanthine oxidase inhibitor therapy to potentially reduce uric acid to very low levels. Is uricosuric therapy helpful, or could the benefits of adding an extra drug be outweighed by adverse events? |

| What is the role of immune modulation/ suppression added to recombinant uricase therapy? | Need to understand how best to use recombinant PEGylated uricase therapy and whether adding it to immune modulation therapy provides better outcomes. Early evidence suggests this off-label approach to be effective. |

| How can pharmacogenomics be applied in uric acid-lowering therapy? | Need to better understand how to use variants of ABCG2, a gene that, when deficient, is linked to early onset and tophaceous gout, and in mice models strongly impacts progression to end-stage renal disease. A quite common variant, ABCG2 Q141K, for example, found in up to ~30% of East Asian populations and up to ~20% of Mexican Americans and Native Americans, is strongly linked to early onset tophaceous gout, and ABCG2 appears to be involved in allopurinol drug resistance. |

Mary Beth Nierengarten is a freelance medical journalist based in Minneapolis.

References

- FitzGerald JD, Dalbeth N, Mikuls T, et al. 2020 American College of Rheumatology guideline for the management of gout. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2020 Jun;72(6):744–760.

- Qaseem A, Harris RP, Forciea MA, et al. Management of acute and recurrent gout: A clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2017 Jan 3;166(1):58–68.

- Mackenzie IS, Ford I, Nuki G, et al. Long-term cardiovascular safety of febuxostat compared with allopurinol in patients with gout (FAST): A multicentre, prospective, randomised, open-label, non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 2020 Nov 9. Epub. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32234-0.