When David Pisetsky, MD, PhD, physician editor of The Rheumatologist, asked me to contribute an article on osteoarthritis, I said yes without hesitation, looking forward to communicating all the exciting new advances taking place regarding osteoarthritis (OA). (Accepting the invitation had its risks. In addition to needing to meet the deadline—which always comes sooner than expected—my wife, Peta, keeps telling me to say no to new academic requests or to stop complaining about being busy!)

There were a number of alternatives—this could be a highly scientific article on everything we know about osteoarthritis (obviously this would be much too long) or a New Yorker–type article with interesting vignettes, a quasi-scientific rendition, or something in between.

After thinking about the content of the article, I decided to write about some of the prevailing quandaries and controversies in the field of osteoarthritis, with respect to etiopathology, guidelines for symptomatic therapy, and our quest for disease modification, the Holy Grail of our search.

I have been an investigator in the osteoarthritis field for almost four decades. I began at a time when the disease was ignored and the victim of a number of myths: it never cripples, it’s an inevitable disease of aging, you can live with the pain without difficulty, and there’s nothing in the way of treatment that really works anyway. Perhaps Sir William Osler was right when he said, “osteoarthritis is an easy disease to take care of—when the patient walks in the front door, I walk out the back door.”

There was a time when, if I gave a lecture on osteoarthritis, five people would show up—three would be technicians in my lab and two would be family members. Now, I have seen 1,500 people attending a lecture on Gene Mutations in Osteoarthritis with a standing room–only audience. The fourth edition of our textbook Osteoarthritis—Medical and Surgical Management, is 750 pages long. We could have added another 750 pages, but the publisher thought that would make the book too costly to sell. Forty years ago, an osteoarthritis textbook would have done well to take up 100 pages. So, with this background, I would like to reflect on OA—what is and what might be.

Table 1: Sources of Pain in OA

Synovium

- Inflammation

Bone

- Medullary hypertension

- Subchondral fracture

Osteophytes

- Periosteal reaction

- Nerve compression

Capsule

- Distension

- Instability

Muscles/Ligaments

- Spasm

- Strain

Pathophysiology and Etiopathology

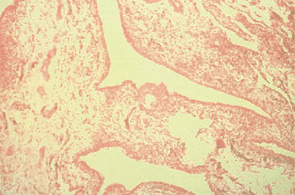

For many years, osteoarthritis was looked at purely as a degenerative disease. (See Figure 1, p. 15.) The analogy was a correlation to erosions that occur over the years as water falls on a rock. It has become obvious over the past decade that osteoarthritis is not only a disease of cartilage and is not only degenerative. Many tissues are involved in the process—subchondral bone characterized by eburnation; synovial involvement characterized by inflammation; bone marrow edema (uncertain pathology but has a relationship to pain); new bone and cartilage formation at the periphery of the joint in the form of osteophytes; inflammatory effusions; and ligamentous and muscle changes.1

In osteoarthritis, inflammation appears to begin early, progressing in parallel with disease worsening. (See Figure 2, p. 15.) Synovitis of involved joints is almost universally seen in patients coming to total joint replacement. The cause of the inflammation is multifold, involving release of inflammatory cytokine mediators, such as IL-1 and TNF-α, and prostaglandins; activation of inflammatory proteases targeted toward destruction of both collagen and proteoglycans; NF-κB activation; and nitric oxide formation.2

Initiation of inflammatory mediator activation and release occurs early with an interplay of responses between synovium and cartilage. It has been hypothesized that suppression of inflammation has the potential to be disease modifying, slowing down disease progression. Perhaps daily intake of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents, if tolerated safely over a prolonged period of time, could be structure modifying as well as pain relieving. Such a hypothesis has yet to be tested.

OA Risk Factor

Major risk factors for OA include age, gender, obesity, heredity, trauma (related to sports or occupation), joint overuse (such as repetitive knee bending), and joint instability or malalignment.3 Does the increased incidence with age result from OA’s asymptomatic early development at age 30 or 40, becoming clinically evident only after 10 or 20 years, or does the aging process itself play a role? There is a suggestion that aging per se may play a role in the form of advanced glycation end products that lead to formation of cross-links between sugars and proteins, making the cartilage more susceptible to injury from other risk factor inputs (obesity, chronic trauma, etc.). Osteoarthritis is more common in women after menopause, possibly relating to estrogen deficiency or (in the case of hand osteoarthritis) genetic predisposition.4

Obesity has a strong relationship to incident osteoarthritis but is even more likely to play a pathogenic role in the presence of joint instability or malalignment. A relationship of osteoarthritis to genetic mutations has been demonstrated, particularly as related to collagen abnormalities.5 Studies suggest that run-of-the-mill osteoarthritis has a hereditary component, with a number of genes under suspicion. Since the only risk factors you can really control at this time are body weight and over- or under-exercise, disease prevention is not easy. Perhaps we ought to be studying not who gets the disease, but who doesn’t get the disease.

Symptomatic Treatment Approaches

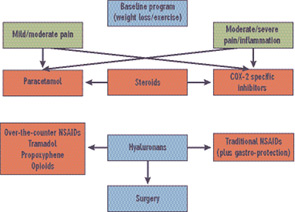

There is an umbrella-like nonpharmacologic approach to management that all patients should receive. Pain in OA has both an inflammatory and non-inflammatory origin. (See Table 1, left.) Therapeutic approaches include weight reduction, appropriate exercise (both joint targeted and nontargeted), avoidance of joint overuse, and use of various orthotics. Unfortunately, most patients require additional analgesic or anti-inflammatory therapy. Guidelines, formulated by the ACR in 2000 (see Figure 3, below right),6 are being reformulated by several groups including the Osteoarthritis Research Society International (OARSI), the European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR), and the ACR. The OARSI recommendations were recently published.7

Recommendations in the ACR guidelines suggested that, after instituting appropriate nonpharmacologic programs, analgesics and anti-inflammatory agents should be considered. The use of acetaminophen in doses up to 4 g per day was recommended as initial therapy. However, in patients with evidence of inflammation or with severe pain, other initial therapeutic approaches, including nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents (NSAIDs) or intra-articular steroids, should be considered. Simple analgesics include acetaminophen followed by agents such as tramadol, propoxyphene, and—in appropriate cases—opioids.

Most patients with OA benefit to various degrees when administered NSAIDs, either traditional nonselective NSAIDs or COX-2 selective agents (called coxibs). COX-2 selective agents have a significant advantage over traditional NSAIDs; they cause fewer adverse gastrointestinal events such as peptic ulcers with associated bleeding, perforation, or obstruction. The observation that some coxibs were associated with an increased rate of cardiovascular events (particularly myocardial infarction) raised concern that increased cardiovascular risk might outweigh the gastrointestinal benefit of the coxibs.8 Coxibs are thought to increase CV risk by causing an imbalance between inhibition of thromboxane and prostacyclin. Coxibs would shift the tendency toward thrombosis by inhibiting prostacyclin, a thrombosis-inhibiting prostaglandin, while not inhibiting thrombosis-promoting thromboxane.

The relationship of nonselective NSAIDs, which effectively inhibit platelets and thromboxane, to CV events is less readily explained.9 Increased thrombotic CV events seen with nonselective NSAIDs may occur because effective inhibition of platelet aggregation requires sustained, over-80% inhibition of platelet COX-1, a level achieved by aspirin and high-dose naproxen. A second mechanism important as a potential cause of increased CV events with NSAIDs of all types, however, relates to increases in hypertension and edema seen to various degrees both with nonselective NSAIDs and coxibs.

A recent statement regarding the treatment of OA by the American Heart Association described a stepped care approach to pharmacologic therapy for osteoarthritis.10 The suggestion was made that initial therapy should include acetaminophen, nonacetylated salicylates, and short-term narcotic analgesics. These recommendations are not evidence based in several respects. Firstly, nonacetylated salicylates (like coxibs) are COX-1 sparing and their potential for increased cardiovascular risk has not been defined. Narcotic analgesics, particularly in older individuals, are associated with significant side reactions, including constipation, cognitive impairment, and the risk of falling. Further, the suggestion that one can differentiate clinical responses to coxibs on the basis of their COX-2–COX-1 specificity ratio has not been clinically validated.

The cardiologists’ suggestion that high-dose aspirin be administered alone as first-line therapy for patients with pain and arthritis might have been true as a recommendation 40 years ago, but I would venture to say that there are few—if any—rheumatologists today who use full doses of aspirin as primary therapy for osteoarthritis.

Source:

ACR Subcommittee on OA Guidelines.

Arthritis Rheum. 2000; 43:1905-1915.

With respect to guidelines for treating OA, the importance of risk versus benefit is, without question, always an uppermost consideration. Unfortunately, pain itself is a cardiovascular risk factor related to increased blood pressure and pulse rate, so lack of pain relief can put the patient at increased risk. Treatment paralysis is not an attractive alternative. Risks of any type are not to be considered lightly, and need to be balanced against relief of pain and improved quality of life—not always an easy decision. Judgment calls by both the patient and physician are important in determining eventual management in any given individual.

Other agents utilized in the symptomatic treatment of osteoarthritis include intra-articular corticosteroids and intra-articular hyaluronans.11 These have the advantage of minimal systemic effects, and are of particular benefit when one or two joints do not respond adequately to other forms of management. At this time, hyaluronans are indicated only for use in osteoarthritis of the knee; they can be considered for use off-label in other joints if appropriate. I have used them in ankle OA with success, and efficacy in OA of the shoulder has been reported. Pre-approval for insurance coverage is recommended.

Glucosamine and chondroitin sulfate have been recommended in the treatment of OA, particularly the knee.12-14 A large study carried out under the auspices of the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculosleletal and Skin diseases and the National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine showed that, in a post-hoc hypothesis-testing analysis, a combination of glucosamine and chondroitin sulfate appeared to be effective in individuals with higher degrees of OA pain.15 Based on clinical studies and experience with OA patients, I recommend use of glucosamine and chondroitin sulfate as adjunctive therapy in management.

Other modalities of therapy may be considered in the overall therapeutic approach. Acupuncture has been shown to be effective in the treatment of OA of the knee, although the effect size is low in most individuals. The increased interest in alternative therapies such as tai chi and yoga has led to increased research in evaluating these techniques. Although some studies support efficacy, investigations utilizing larger numbers of subjects in double-blinded studies would add to our knowledge in this arena.

Disease Modification

The elusive target of osteoarthritis management is disease modification with prevention of OA onset or (probably more achievable) retardation of disease progression. At this time, there are no specific agents approved for disease modification. Some studies do suggest that certain agents are associated with a slowing of disease progression, including glucosamine sulfate, chondroitin sulfate, sodium hyaluronan, soybean-avocado extract, and diacerrein.16 Identification of drugs as structure modifying is particularly challenging given that there is disagreement as to the best outcome measure for defining such structure modification. Classically, a slowing of joint-space narrowing (a measure of cartilage loss) has been the gold standard for demonstrating inhibition of disease progression. MRI will detect structural changes earlier and more comprehensively than radiologic study of joint-space narrowing alone.17

Using joint-space narrowing as a measure of structural change is dependent on the accuracy of X-ray measurement, not an easily achievable goal. In the past, standing X-rays have been routinely used in study performance. It has been subsequently shown that more accurate definition of joint-space responses can be made using special positioning techniques which involve semiflexed knee positions.18 In an upright position, the joint space appears wider than when studied in a semiflexed position.

As noted, osteoarthritis is a disease not only of cartilage but also of other joint tissues. Accordingly, MRI measures which investigate the whole joint (so called WORMS) are important in designing structure-modification studies.17

Biomarkers

There is a great deal of interest in using biomarkers found in the serum and urine to provide earlier clues to structural disease changes, particularly as they relate to therapeutic responses to disease-modifying agents.18 At this time, biomarkers have limited effectiveness for assessing disease modification. Biomarker assessment is complicated by the fact that osteoarthritis is frequently multi-articular. A given patient may have early as well as late osteoarthritis in various joints, so a biomarker to identify OA responses in one specific joint will be confounded by biomarker responses related to other joints with OA not being assessed. C-telopeptide-II, a biomarker measuring type-II collagen breakdown, seems be the most promising of these biomarkers.

Markers of inflammation including hyaluronans and C-reactive protein may help identify patients more likely to have increased rates of disease progression, based on studies demonstrating a positive correlation. This may be because these are measures of inflammation, which is associated with more severe and rapid disease advancement.

Surgical Approaches

Partial or total joint replacement, particularly in the knee or hip, is recognized as a major advance in decreasing pain and increasing quality of life in patients with late-stage osteoarthritis. New procedures, including minimally invasive techniques and uni-compartmental replacement rather than total knee replacement, represent additional improvements offering faster rehabilitation and fewer complications. Surface replacement in the hip in carefully selected patients allows maintenance of bone stock and increases opportunities for additional therapeutic alternatives if future surgery is required.

Conclusion

We know a great deal more about OA etiopathogenesis and treatment than we did even a short time ago. The therapeutic advances have not, unfortunately, been as striking as those that have occurred over the past decade in the management of RA. Advances in our knowledge of disease pathophysiology, however, auger well that agents capable of better and safer symptomatic control and disease modification will be forthcoming.

Interest in OA from investigators, governmental agencies, nonprofit institutions, and pharmaceutical companies is at an all-time high—an appropriate response to the ever-increasing burden we can expect in the aging baby-boomer population over the next decade. I am hopeful that, down the line, when Dr. Pisetsky asks me to write an update on OA treatment, we will have found “Dr. Ehrlich’s Magic Bullet” for OA.

Dr. Moskowitz is professor of medicine at Case Western Reserve University and director of the Rheumatology Clinical Research Center at University Hospitals, both in Cleveland. The editorial assistance of Ann Awadalla, rheumatology clinical research center student intern, is appreciated.

References

- Felson DT, Kim YJ. The futility of current approaches to chondroprotection. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56(5):1378-1383.

- Pelletier JP, Martel-Pelletier J, Abramson SB. Osteoarthritis, an inflammatory disease: potential implication for the selection of new therapeutic targets [review]. Arthritis Rheum. 2001;44:1237-1247.

- Moskowitz RW, Altman, RD, Hochberg, M, Buckwalter, J, Goldberg, VM. Osteoarthritis—Diagnosis and Management. 4th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2006.

- Abramson SB, Honig S. Antiresorptive agents and osteoarthritis: More than a bone to pick? Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56:2469-2473.

- Holderbaum D, Haqqi TM, Moskowitz RW. Genetics of osteoarthritis: Exposing the iceberg. Arthritis Rheum. 1999;42:397-405.

- ACR Subcommittee on Osteoarthritis Guidelines. Recommendations for the medical management of osteoarthritis of the hip and knee. Arthritis Rheum. 2000; 43:1905-1915.

- Zhang W, Moskowitz RW, Nuki G, et al. OARSI recommendations for the management of hip and knee osteoarthritis, Part II: OARSI evidence-based, expert consensus guidelines. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2008;16:137-162.

- Moskowitz RW, Abramson SB, Berenbaum F, Simon LS, Hochberg M. COXibs and NSAIDS—Is the air any clearer? Perspectives from the OARSI international COX-2 workshop 2007. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2007;15(8):849-856.

- Singh G, Mithal A, Triadafilopoulos G. Both selective COX-2 inhibitors and non-selective NSAIDs increase the risk of acute myocardial infarction in patients with arthritis: Selectivity is with the patient, not the drug class. Ann Rheum Dis. 2005;64:S85-S86.

- Antman EM, Bennet JS, Daughtery A, et al. Use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs: An update for clinicians. Circulation. 2007;115:1634-1642.

- Altman RD, Moskowitz RW. Hyaluronate sodium injections for osteoarthritis. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162:2498-2499; author reply 2499-2500.

- Reginster JY, Deroisy R, Rovati LC, et al. Long-term effect of glucosamine sulfate on osteoarthritis progression: a randomized placebo-controlled clinical trial. Lancet. 2001;27:251-265.

- McAlindon TE, LaValley MP, Gulin JP, et al. Glucosamine and chondroitin for treatment of osteoarthritis: a systematic quality assessment and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2000;283:1469-1475.

- Leeb BF, Schweitzer H, Montag K, et al. A meta-analysis of chondroitin sulfate in the treatment of osteoarthritis. J Rheumatol. 2002;27:205-222.

- Clegg D, Reda D, Harris H, et al. Efficacy of glucosamine, chondroitin sulfate, and the combination in painful knee osteoarthritis. N Eng J Med. 2006;354:797-808.

- Moskowitz RW, Hooper M. State-of-the-art disease-modifying osteoarthritis drugs. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2005;7:15-21.

- Peterfy CG, Guermazi MD, Zaim MD, et al. Whole-organ magnetic resonance imaging score (WORMS) of the knee in osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2004; 12:177-190.

- Brandt KD, Mazucca SA, Conrozier T, et al. What is the best radiographic protocol for clinical trial of a structure modifying drug in patients with osteoarthritis. J Rheumatol. 2002;29:1308-1320.

- Garnero P, Ayral X, Rousseau JC, et al. Uncoupling of type II collagen synthesis and degradation predicts progression of joint damage in patients with knee osteoarthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2002;46(10):2613-2624.