To understand pain mechanisms that may operate in RA, fibromyalgia provides an important model. Fibromyalgia is a condition associated with chronic widespread pain. Many patients with this condition also experience fatigue, cognitive difficulties, sleep problems, and mood and anxiety disorders. In contrast to RA, fibromyalgia is not associated with obvious peripheral causes of pain; instead, studies have suggested that the etiology of fibromyalgia pain lies in the CNS.

The clinical pain experienced by fibromyalgia patients may be due to enhanced pain sensitivity. When exposed to noxious experimental stimuli, fibromyalgia patients report pain at lower stimuli intensities compared to controls.4 This increased pain sensitivity occurs at numerous sites across the body. Functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) studies show corresponding changes in brain activity when fibromyalgia patients are exposed to a painful stimulus. These activations are not observed among healthy individuals who are exposed to a stimulus of the same magnitude but who do not consider the stimulus to be painful. However, if the magnitude of the stimulus is increased such that healthy individuals rate the stimulus at the same pain level as the stimulus provided to fibromyalgia patients, then brain activation is observed in the same areas.5 These observations strongly support the hypothesis that fibromyalgia patients are more sensitive to noxious stimuli than are healthy controls.

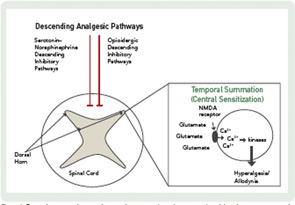

The CNS mechanisms that modulate pain in fibromyalgia involve: 1) dampening of descending analgesic pathways; and 2) augmentation of excitatory pain pathways (see Figure 1). The descending analgesic pathways originate in the cortical structures, hypothalamus, and brainstem and pass through the spinal cord to regulate sensory input from primary afferent fibers. These pathways act through serotonin, norepinephrine, and endogenous opioids, molecules that block excitatory neurotransmitter release, thereby dampening pain sensitivity. The descending serotonergic–adrenergic pathways are often impaired in fibromyalgia patients relative to those in healthy controls, and this impairment is associated with greater pain sensitivity and clinical pain severity. This deficit in inhibitory pain regulation is termed loss of “descending analgesia” or “diffuse noxious inhibitory controls.”

In addition to a loss of descending analgesia, some fibromyalgia patients also exhibit enhanced temporal summation, otherwise known as central sensitization. Temporal summation describes the phenomenon by which repetitive painful stimuli lead to the lowering of pain thresholds and heightened pain sensitivity. This process is mediated by the excitatory neurotransmitters, glutamate and substance P. These molecules activate N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor channels, leading to an influx of calcium ions which activate kinases that lower the pain threshold. These changes in CNS processing have implications for pharmacological and nonpharmacological treatment.

Pain Mechanisms in RA

In contrast to the situation in fibromyalgia, the role of augmented CNS pain processing in systemic inflammatory diseases, such as RA, is not well established. Several studies have reported that the prevalence of fibromyalgia is higher among patients with rheumatic diseases associated with peripheral pain and inflammation than among control populations. The prevalence of fibromyalgia ranges from 13% to 22% among patients with RA, compared to only 2.5% for healthy controls.6,7 Which RA patients are at risk for secondary fibromyalgia is not clear, although a recent study suggested that the development of fibromyalgia in RA is associated with psychosocial distress, comorbidities, and sociodemographic disadvantages.8