Several quantitative sensory studies have shown that RA patients are more likely to have widespread pain sensitivity than are healthy controls.9 This sensitivity occurs at both joint and nonjoint sites, suggesting a dysfunction in CNS pain processing rather than site-specific, peripheral changes. Although pain thresholds at joint sites are associated with both inflammatory (e.g., increases in C-reactive protein) and noninflammatory factors (e.g., sleep problems), pain thresholds at nonjoint sites are only associated with noninflammatory factors.10 This pattern of association is consistent with two mechanisms of pain: 1) a peripheral mechanism associated with inflammation; and 2) a central mechanism associated with a symptom complex that includes sleep problems, fatigue, and changes in mood.

To date, only one study has specifically assessed the role of descending analgesia in RA. This study documented a smaller magnitude of descending analgesia among RA patients compared to healthy controls, but the difference was not statistically significant.11

Pain Assessment in RA

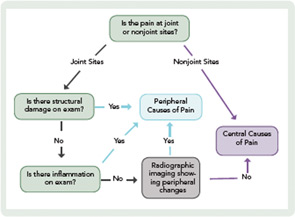

Although future studies are needed to clarify the role of central pain mechanisms in RA, it is essential that rheumatologists implement comprehensive pain assessment and management strategies now. Routine pain assessment should include a thorough history and physical exam, as well as careful consideration of radiographic imaging. Key points to consider are the following: 1) the location of pain; 2) the presence of inflammation; and 3) the presence of structural damage (see Figure 2).

When assessing the location of pain, the main distinction is whether the pain is at joint or nonjoint sites. Pain at joint sites is more likely to be RA-related than pain at nonjoint sites. However, many patients may have pain at joint sites but no signs of inflammation or structural damage on physical examination. In these patients, it may be helpful to perform radiographic imaging via ultrasound or MRI to look for evidence of synovitis or erosions.

In the absence of radiographic findings, dysregulation of central pain processing mechanisms should be suspected, prompting the assessment of comorbid fibromyalgia. This assessment may be aided by the new ACR clinical and survey criteria for the diagnosis of fibromyalgia.12,13 These criteria do not require physical examination but are based on self-report measures that assess widespread pain and other symptoms (see Table 1).13 It is also important to ask the patient about fatigue, poor sleep, subjective cognitive problems, and/or psychiatric comorbidity (predominantly mood disturbance and anxiety). These symptoms are frequently present and can contribute, either individually or in concert, to the pain experience.