Rheumatology is such a gratifying and emotionally rewarding medical specialty. There is no better feeling than helping patients with conditions whose proper diagnosis and management have eluded other practitioners. To our grateful patients, we are their Dr. House, the superstar doctor. Since we only number about 6,000 in the United States and there are probably no more than 12,000 rheumatologists practicing worldwide, most of us get the opportunity to develop large and diverse clinical practices.

I recall one particularly interesting Thursday morning clinic from years gone by. This morning session seemed to be the best time for me to see new referrals. I really enjoy meeting new patients; they each present as a puzzle in need of a solution. What a fascinating game. Here are the rules: the patient tells you their story and you parse through those key tidbits of information from their tale and add them to those observations gleaned from your careful physical exam. Listen carefully, observe critically, and voila! Case solved. Sometimes.

Lessons from a Thursday Clinic

My first patient that morning was a pleasant guy with a pretty straightforward problem. I thought he had a familiar-sounding name, but I couldn’t seem to place it until I stared at his problem list on the top corner of his electronic medical record and noticed that his primary-care physician had inserted “Nobel Laureate” as problem No. 1. We should all suffer from such problems. Anyway, he just needed some straightforward advice to remedy his benign musculoskeletal problem. Weeks later, Mr. Nobel was kind enough to send me a thank-you note along with a copy of his Stockholm acceptance speech. A grateful patient!

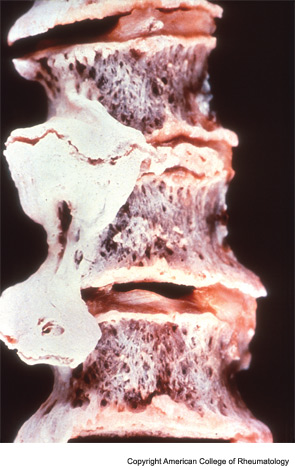

My next patient was a 50-something-year-old man complaining of an aching back. He had been referred to me because his doctor suspected he had an unusual spine disease that needed the expertise of a rheumatologist. He described how his pain was so severe that he had to quit his job as a plumber. His life was miserable and no doctor could seem to help him. He described his entire low back as being sore to touch. For a moment I considered following William Osler’s quip: “When a patient with arthritis walks in the front door, I feel like leaving out the back door.” His physical exam was not unusual for someone with these complaints. He was out of shape and had trouble bending forward. He brought along a voluminous radiology file. I reviewed his spine films and noted a couple of large, thorny-looking osteophytes protruding from his lower thoracic and upper lumbar vertebra. Clearly he had diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis (DISH).