Rheumatology is such a gratifying and emotionally rewarding medical specialty. There is no better feeling than helping patients with conditions whose proper diagnosis and management have eluded other practitioners. To our grateful patients, we are their Dr. House, the superstar doctor. Since we only number about 6,000 in the United States and there are probably no more than 12,000 rheumatologists practicing worldwide, most of us get the opportunity to develop large and diverse clinical practices.

I recall one particularly interesting Thursday morning clinic from years gone by. This morning session seemed to be the best time for me to see new referrals. I really enjoy meeting new patients; they each present as a puzzle in need of a solution. What a fascinating game. Here are the rules: the patient tells you their story and you parse through those key tidbits of information from their tale and add them to those observations gleaned from your careful physical exam. Listen carefully, observe critically, and voila! Case solved. Sometimes.

Lessons from a Thursday Clinic

My first patient that morning was a pleasant guy with a pretty straightforward problem. I thought he had a familiar-sounding name, but I couldn’t seem to place it until I stared at his problem list on the top corner of his electronic medical record and noticed that his primary-care physician had inserted “Nobel Laureate” as problem No. 1. We should all suffer from such problems. Anyway, he just needed some straightforward advice to remedy his benign musculoskeletal problem. Weeks later, Mr. Nobel was kind enough to send me a thank-you note along with a copy of his Stockholm acceptance speech. A grateful patient!

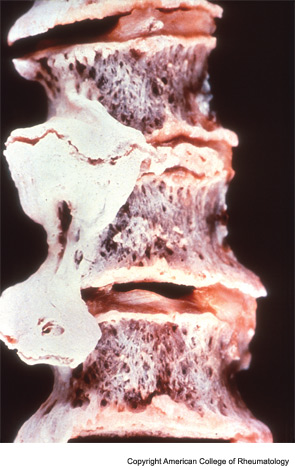

My next patient was a 50-something-year-old man complaining of an aching back. He had been referred to me because his doctor suspected he had an unusual spine disease that needed the expertise of a rheumatologist. He described how his pain was so severe that he had to quit his job as a plumber. His life was miserable and no doctor could seem to help him. He described his entire low back as being sore to touch. For a moment I considered following William Osler’s quip: “When a patient with arthritis walks in the front door, I feel like leaving out the back door.” His physical exam was not unusual for someone with these complaints. He was out of shape and had trouble bending forward. He brought along a voluminous radiology file. I reviewed his spine films and noted a couple of large, thorny-looking osteophytes protruding from his lower thoracic and upper lumbar vertebra. Clearly he had diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis (DISH).

I explained why I disagreed with his prior diagnosis of ankylosing spondylitis and how these prominent bony spurs were not likely causing his back pain. “They were just placed there to confuse your doctors,” I said. I recommended some simple stretching exercises and, if he was motivated, for him to try some physical therapy. He was so grateful! “Thank you doctor, I have been to so many doctors and you are the first one who explained what is wrong with my back and what I need to do about it.” He did not require any pain medication—or so I thought; about an hour later I realized that my prescription pad was missing. He must have had a fleeting opportunity to grab it when I turned my back to study his X-rays. So much for his so-called loss of mobility! Two days later a local pharmacy was paging me to confirm my “prescription” for 200 tablets of a brand name of oxycodone. The following day there was another call, but this time the prescription was for generic oxycodone.

A call to the state police confirmed that Mr. DISH had 22 other similar citations for what is euphemistically known in the Commonwealth of Massachusetts as “uttering a false prescription.” Such a grateful patient! I wondered whether he used this ruse of an abnormal-appearing spine X-ray to extract authentic narcotic prescriptions from unsuspecting physicians. After all, DISH isn’t supposed to be symptomatic, but I doubt that nonrheumatologists are aware of this fact.

For the next few weeks, I became obsessed with DISH. Maybe the shock of having to deal with my medical identity theft made me determined to learn all I could about this obscure condition. So what is DISH? Is it really just a radiographic phenomenon seen in older men carrying little, if any, clinical significance? Why does it develop in the first place? As I delved deeper into the topic, I came to realize that DISH is one of those arcane, truly fascinating rheumatologic conditions with a rich history that spans civilizations.

Did you know that pathognomonic osteophytesin DISH are almost always seen on the right side of the vertebra, except in cases of dextrocardia or situsinversus? Talk about a great trivia question for your next cocktail party!

Some Definitions

Jacques Forestier and Jaume Rotés Querol first described this radiographic finding in 1950 and termed it senile ankylosing hyperostosis of the spine. They defined it as “an ankylosing disease of the spine developing in old people with a painless onset and clinical, pathological, and radiological features distinguishing it from ankylosing spondylitis.” There were about six different names given to this condition before Donald Resnick, one of the great musculoskeletal radiologists, renamed the entity DISH and established diagnostic criteria requiring the involvement of at least four contiguous vertebrae of the thoracic spine with preservation of the intervertebral disc space and an absence of any apophysealor sacroiliac joint inflammatory changes. Nowadays, most clinicians consider DISH when they spot those pathognomonic osteophytes coursing over the anterolateral aspect of the thoracic spine. Did you know that they are almost always seen on the right side of the vertebra, except in cases of dextrocardia or situsinversus? Talk about a great trivia question for your next cocktail party!

Paleorheumatology

To learn more about DISH, we need to travel back to 15th-century Italy. Natale Villari and a group of researchers working at the Universities of Florence, Pisa, and Siena have studied the exhumed remains of the Medici family. The Medici was one of the richest and most powerful families of the Italian Renaissance. Beginning in the 14th century, through careful management of banking ventures and skillful political action, the family rose to the pinnacle of social and political power in the city of Florence in the Tuscany region of Italy, which the Medici made the intellectual center of the Western world for the next two centuries. Members who included Cosimo “the Elder,” Piero “the Gouty,” and Lorenzo “the Magnificent” were lovers of the arts and sciences and patrons of Michelangelo, da Vinci, Botticelli, and Galileo.

Detailed paleontological studies demonstrated a high degree of prevalence of DISH in the Medici clan, suggesting an association between DISH and elite status. Further studies have linked DISH with a high-caloric diet, obesity, and type 2 diabetes mellitus. The Italian Renaissance aristocratic classes had access to a wide variety of foods. Historical data and carbon isotope dating reveal that their diet was primarily based on wine and meat, occasionally enriched by eggs and cheese and, on penitential occasions, by fish. In contrast, the consumption of vegetables was scarce and fruit was almost never eaten. Not surprisingly, several of the DISH-afflicted members of the Medici family were also found to have suffered from gout. Ouch.

If you look hard enough, you will find DISH in many other famous remains including the Egyptian pharaoh Ramses II and in hominid specimens as old as the Neandertal Shanidar I, who lived approximately 50,000 years ago. Our colleague, Bruce Rothschild, working with anthropologists from the University of Nevada, has identified DISH in the skeletal remains of about one in eight Nubian males who resided in northern Sudan a few thousand years ago. The Nubians were a nomadic tribe of hunters and gatherers. They had access to food, and archeological evidence suggests that they were well nourished. Being well fed is a recurrent theme in the DISH story. Dr. Rothschild has suggested that there may have been an evolutionary benefit to having DISH. The paravertebral bone deposition could have protected the host against the development of neuroforaminal narrowing by providing additional bracing support to the aging spine. In a world of kill or be killed, undoubtedly it was far more advantageous to have DISH than lumbar spinal stenosis.

Metabolic Factors

An intriguing study by Juliet Rogers and Tony Waldron found DISH to be present in six out of 52 excavated males of the population buried in the church and chapels from The Royal Mint Medieval site in London, while the prevalence of DISH in a nearby lay cemetery where the general population (likely to be peasants and farmers)was buried was zero out of 99 males. They suggested that this disparity was due to a difference in occupation and social class resulting indifferent diets. Similar findings have been noted in studies of Dutch clergy. Prior descriptions of the dietary habits of monks in the Middle Ages indicate that saturated (animal) fats combined with small portions of vegetables and ample alcoholic beverages were frequently on the menu, not unlike the current diet in many Western societies.

So what might be the metabolic link connecting obesity, diabetes, and DISH? It has been observed that insulin-like growth factor-I stimulates alkaline phosphatase activity in osteoblasts and that growth hormone can induce the local production of this factor and its binding proteins in chondrocytes and osteoblasts. DISH patients have elevated insulin and growth hormone levels, which may explain the robust osteoblast cell growth and proliferation seen in this condition.

Other studies have suggested possible roles for matrix Gla protein, bone morphogenetic protein-2, and possibly leptin. Dickkopf-1 (DKK-1) is an inhibitor of osteoblastogenesis. Higher levels of DKK-1 are related to bone resorption, whereas lower levels are linked to new bone formation. A recent study observed that total circulating DKK-1 levels are lower in patients with DISH and may correlate with the severity of spinal involvement.

What About Pain?

So what about pain in patients with DISH? A major clinical tenet has been the lack of an association between DISH and pain. Based on this assumption, I dismissed the painful back symptoms described by my ungrateful patient. The literature on this subject is scant, but one of the best-designed studies to address this issue actually observed a reduction in self-reported incidences of back pain in elderly men with DISH compared with age-matched controls. There may be a corollary to this observation; that is, the presence of pain should suggest other possible causes of back pain such as occult vertebral fracture. On the other hand, the cervical spine region involvement by DISH can be more problematic for two reasons. First, some of the more sizable osteophytes may impinge on the adjacent esophageal structures resulting in dysphagia. Second, there may be ligamentous calcification adjacent to the spinal cord. Non-Asian patients with DISH generally have ossification of the anterior longitudinal ligament developing anywhere along the spine. Since this ligament sits on the far side of the vertebra, away from where the cervical or thoracic spinal cord resides, it cannot impinge or irritate the cord. This is not the case for the posterior longitudinal ligament.

In some DISH patients, primarily those of Asian descent, there is a curious condition known as ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament (OPLL). It can be seen in about 2% of the Japanese population, though the majority of patients are asymptomatic. Since the posterior longitudinal ligament and the spinal cord are neighbors, any excessive calcification in this area can cause extreme neck pain with nuchal rigidity mimicking meningitis. Sometimes it can present as a cervical myelopathy with extremity numbness and weakness.

I happened to meet a young woman who had the misfortune of experiencing these symptoms. She was 37 years old, born to an Irish mother and a father from the Philippines. She never experienced any back or neck problems until her “Night of Hell.” She awoke from a sound sleep with the worst imaginable headache and arm numbness. She could not move her neck at all. Her partner drove her to the local hospital emergency room where, for some strange reason, the doctors were not impressed. They gave her a prescription for hydrocodone and sent her home. Two hours later, she presented to our emergency room in total misery.

The immediate concern was that she was experiencing a catastrophic intracranial event, either acute meningitis or an intracranial bleed. Neuroimaging identified the problem. There was a great deal of bone deposition coursing along the OPLL as it wove through its congested neighborhood. That evening, she underwent an extensive corpectomy of nearly the entire cervical spine. She was referred to me after her discharge from hospital. Although she was grateful to be alive and able to walk, she was still miserable because of the pain. She had already tried a variety of analgesics without much benefit. She was hoping that I could offer her “some kind of miracle drug.” Sadly, that would not be the case. We reviewed her films and I was amazed to see how much orthopedic hardware was required to stabilize her neck. No wonder she was so miserable, but unfortunately there was nothing I could recommend to lessen the pain. When I turned back from the X-ray viewer to my desk, I noticed that my prescription pad was just where I had left it. Untouched.

Dr. Helfgott is physician editor of The Rheumatologist and associate professor of medicine in the division of rheumatology, immunology, and allergy at Harvard Medical School in Boston.