Physical inactivity is the fourth leading risk factor for global mortality, resulting in an estimated 3.3 million deaths a year globally, accounting for 6% of global deaths.1,2 A sedentary lifestyle (i.e., too much sitting) is associated with an increased risk for all-cause and chronic disease-related morbidity and mortality, including cardiovascular disease, diabetes, metabolic syndrome, various cancers and obesity.3,4 People living with rheumatoid arthritis (RA) will experience several additional benefits from being more physically active, including improved mobility, strength, physical functioning, mood and bone health, as well as reduced fall risk, with little risk of increased pain or joint damage.5,6 However, despite the clear health benefits of a more active lifestyle, people living with RA remain less active than their age- and gender-matched peers.7-9

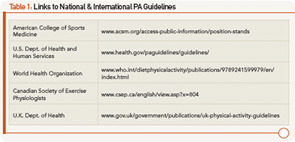

The health promotion message of Exercise More, with the goal of meeting weekly physical activity (PA) guidelines for moderate- or higher-intensity aerobic exercise, is widely adopted.2,10,11 International guidelines recommend that adults aged 19–65 acquire at least 150 minutes (two-and-a-half hours) of moderate-effort aerobic activity each week, accumulated in bouts of at least 10 minutes, to receive health benefits. Guidelines also suggest that similar benefits can be achieved with 75 minutes (one and one-quarter hours) of more vigorous activities, similarly acquired in sessions of 10 minutes or more over a week. Additionally, it is recommended that adults also include strengthening, flexibility and balance-type activities two or three days a week2,10-11 (see Table 1).

The health promotion message of Sit Less is also becoming more widely known.12 Adults in North America spend up to 60% of their waking time (i.e., nine hours or more each day) sitting or lying still.13 Replacing time spent sitting or lying around while awake with activities that involve standing up and moving around a little bit reduce the health risks associated with a sedentary lifestyle.14 Moreover, the health benefits associated with being less sedentary have been shown to be independent of whether or not the same person is also meeting PA guidelines.15

Notably, the specific health benefits associated with reducing sedentary behaviors for people living with RA have not been specifically explored. However, it can be argued that the message of some light activity is better than none may have even more relevance for someone living with RA, whose pain and fatigue can play roles in limiting their ability to participate in higher-intensity activities.16 Additionally, encouraging people living with RA to replace prolonged sitting with light activities fits well with our other health messages around the importance of joint protection, pacing and energy conservation.

What Does “Exercise More” Mean?

Every day, adults living with RA should plan to do two to three moderate-to-vigorous-effort physical activities that they need to do or like to do and can do comfortably for at least 10 minutes. Note:

People living with RA should aim for 20 to 30 minutes of moderate-effort activities every day, done in bouts of 10 minutes or more at a time.

- Moderate effort means the heart rate, breathing and body temperature will increase a little bit with activity, but the person can still talk or carry on a conversation without difficultly. At the end of a moderate-effort activity, a person should feel refreshed. Moderate-effort activities include purposeful walking around 3 mph (>100 steps/minute), standing and intermittent walking activities that require moderate upper-extremity use, such as raking leaves and circuit-based low-resistance training.

- Need to do includes activities that need to be done regularly as part of the normal weekly routine (e.g., walking the dog, vacuuming or gardening) or occupational activities (e.g., walking from the bus stop/car to work, packing boxes for shipping or moving).

- Like to do means working leisure or recreational activities into your weekly plan that are both enjoyable and include an element of socialization (e.g., walking with a friend, attending a pool exercise class, fishing while standing—not sitting).

- Comfortable means there should be no additional joint discomfort or swelling during or immediately after the activity. New activities should be introduced gradually and monitored to ensure there is no increase in disease activity with progressing both the effort and time doing the activity.

- People living with RA do not need to participate in more vigorous activities to achieve the health benefits associated with aerobic physical activity. However, there are many potential physical and emotional health benefits to participating in higher-intensity activity, as long as there is no increase in fatigue or joint symptoms.17 Note the following:

- Vigorous-effort activities generally leave a person tired, sweaty and a little short of breath after a few minutes and include activities that most people traditionally consider exercise, such as jogging, climbing several flights of stairs or using a push mower.

- Participation in vigorous physical activities should be introduced gradually, beginning with a trial session of 10 minutes or less, depending on joint symptoms. This trial should be followed by a day with no vigorous activity to monitor if the new activity is contributing to an increased level of fatigue or acute joint symptoms.

- Balancing the amount of time doing moderate- vs. vigorous-effort activities during any one activity session (e.g., 10 minutes of activity = five minutes of brisk walking [moderate effort] + five minutes of jogging [vigorous effort]) can be a helpful way to self pace and reduce the overall physical stresses to the body and joints while also gaining the additional health benefits from a more physically active lifestyle.

What Does “Sit Less” Mean?

Breaking up sitting time by standing up to stretch and take a few steps every 20–30 minutes will reduce sedentary time by about two minutes.

Two common leisure activities that people do in sitting for more than 30 minutes include screen-time activities (e.g., watching TV/movies, playing video games, surfing the Web on their computer or mobile device) and reading.

Standing up & stretching during TV commercials & after each computer game or chapter in a book & limiting leisure screen-time activities to less than two hours a day are simple ways to reduce leisure-time sedentary behaviors.

Three common occupational activities that people do while sitting for more than 30 minutes include working at a desk/computer, meetings and commuting for work. It’s easy to reduce occupational sitting by standing up and stretching every half hour when working at the computer and during meetings, standing up to talk on the phone, using the stairs (e.g., one floor up, two floors down), and having standing or walking meetings.

- Adding 100 steps or 50 meters of slow leisurely walking to home and work activities will reduce sedentary time by two minutes. Try walking 50 meters (i.e., the length of an Olympic-sized swimming pool or a short city block) to and from five home- or work-based activities. This will add 1,000 steps or 20 minutes of light activity into your day.

You Won’t Know If You Don’t Ask: 2 Simple Screening Questions

Physical Activity Screening Question: In the past week, approximately how many days did you do at least one walking or other moderate-to-vigorous physical activity that lasted 10 minutes or more? Note: In other words, your heart rate, breathing and body temperature would have increased slightly during the activity, but you could still talk without difficulty while doing the activity.

Interpretation

- Active: five to seven days with 20–30-plus minutes of moderate-effort activity.

- Fairly Active: five to seven days a week with 10–20 minutes of moderate-effort activity.

- Less Active: three to four days a week with 10–20 minutes with moderate-effort activity.

- Inactive: two or fewer days a week with 10–20 minutes of moderate-effort activity.

Sedentary Behavior Screening Question: In the past week during your leisure time, approximately how many hours a day did you spend sitting or lying still doing screen-time-related activities? Note: Screen-time activities include watching TV/movies, playing video games or surfing the Web on your computer or mobile device.19

Routinely asking patients about their normal physical activity & sedentary behaviors will help you understand when & what additional information or support may be needed to assist them to become more active & sit less throughout the day.

Interpretation

- Very Sedentary: >two hours a day of leisure screen-time activities.

- Sedentary: one to two hours a day of leisure screen-time activities.

- Minimally Sedentary: less than an hour a day of leisure screen-time activities.

- Non-Sedentary: no leisure screen-time activities.

What You Can Do

You can help people living with RA develop and maintain a physically active lifestyle. Some tips:

- Active: Acknowledge that the person is likely meeting PA guidelines and encourage ongoing physical activity. Ask about how much higher-intensity/vigorous activity they are doing each week, and refer them for advice if they are possibly doing too much exercise (i.e., complaining of joint pain or increased fatigue after vigorous activities).

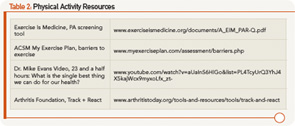

- Fairly Active: Acknowledge that the person is close to meeting PA guidelines, and encourage an ongoing physically active lifestyle. Offer some individualized advice and support for ways to increase their PA, and provide information and resources that will help them maintain their motivation (see Table 2).

- Less Active: Explore the person’s readiness and motivation to change their PA behaviors, and explore their possible barriers to being more physically active (see Table 2). Provide some individualized support with problem solving, goal setting and action planning to improve their PA behaviors or refer them to an arthritis-trained health professional to provide this support.

- Inactive: Refer them to an arthritis-trained health professional to assess the person’s readiness and motivation to change their PA behaviors and explore possible barriers to being more physically active through individualized support to increase their activity.

Some tips for how you can support people living with RA to be less sedentary:

- Non-Sedentary: Ask about other sitting behaviors/activities besides screen-time activities that they may be doing for long periods of time during their leisure time. Acknowledge their non-sedentary lifestyle, and reiterate the important health benefits of doing a little bit of activity frequently throughout the day. Encourage pacing, rest and energy conservation as important elements of self-management in RA.

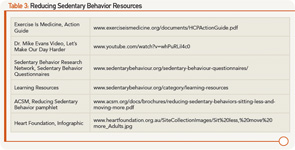

- Minimally Sedentary: Ask about other sitting behaviors/activities as above and acknowledge their minimally sedentary lifestyle. Discuss the health benefits of doing a little bit of activity frequently throughout the day. Provide additional information on and resources for ways to reduce sitting in their day (see Table 3).

- Sedentary: Explore the person’s readiness and motivation to change their sedentary behaviors and discuss possible reasons for or barriers to not reducing their sedentary behaviors (see Table 3). Provide some guidance or support on reducing sedentary time or refer them to an arthritis-trained health professional who can provide more individualized support through problem solving, goal setting and action planning.

- Very Sedentary: Refer them to an arthritis-trained health professional for an evaluation of readiness and motivation to change their sedentary behaviors and overcome their barriers to reducing sedentary behaviors, and individualized support to reduce sedentary behavior.

Summary

Encouraging more physical activity and less sitting throughout the day are equally important health and lifestyle messages that we should reinforce with every patient living with RA. To support our RA patients to exercise more and sit less, it’s important that we understand what these messages mean in terms of actual behaviors to screen for and encourage in our patients. It is particularly important to refer newly diagnosed RA patients or those with moderate to higher levels of disease activity to an arthritis-trained health professional for individualized support and guidance on safe and appropriate physical activities and minimizing sedentary behaviors.

Lynne Feehan, PhD, PT, is the leader, clinical research for rehabilitation in the Fraser Health Authority in British Columbia and a clinical associate professor in the Department of Physical Therapy at the University of British Columbia, Vancouver, Canada.

Marie Westby, PhD, PT, is the physical therapy teaching supervisor in the Mary Pack Arthritis Program, Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada, a postdoctoral fellow in the School of Public Health, University of Alberta, Edmonton, Alberta, Canada, and a member of the ARHP Practice Committee.

References

- World Health Organization. Global health risks. 2009. http://www.who.int/healthinfo/global_burden_disease/global_health_risks/en/index.html

- World Health Organization. Global recommendations on physical activity for health. 2010. http://www.who.int/dietphysicalactivity/publications/9789241599979/en/index.html.

- Matthews CE, George SM, Moore SC, et al. Amount of time spent in sedentary behaviors and cause-specific mortality in US adults. Am J Clin Nutr. 2012 Feb;95(2):437–445.

- Thorp AA, Owen N, Neuhaus M, et al. Sedentary behaviors and subsequent health outcomes in adults. A systematic review of longitudinal studies, 1996–2011. Am J Prev Med. 2011 Aug;41(2):207–215.

- Conn VS, Hafdahl AR, Minor MA, et al. Physical activity interventions among adults with arthritis: Meta-analysis of outcomes. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2008 Apr;37(5):307–316.

- Plasqui G. The role of physical activity in rheumatoid arthritis. Physiol Behav. 2008 May 23;94(2):270–275.

- Munsterman T, Takken T, Wittink H. Are persons with rheumatoid arthritis deconditioned? A review of physical activity and aerobic capacity. BMC Musculoskel Disord. 2012 Oct 18;13:202.

- Tierney M, Fraser A, Kennedy N. Physical activity in rheumatoid arthritis: A systematic review. J Phys Act Health. 2012 Sep;9(7):1036–1048.

- Prioreschi A, Hodkinson B, Avidon I, et al. The clinical utility of accelerometry in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2013 Sep;52(9):1721–1727.

- Garber CE, Blissmer B, Deschenes MR, et al. American College of Sports Medicine position stand. Quantity and quality of exercise for developing and maintaining cardiorespiratory, musculoskeletal, and neuromotor fitness in apparently healthy adults: Guidance for prescribing exercise. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2011 Jul;43(7):1334–1359.

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The Surgeon General’s vision for a healthy and fit nation. Rockville, Md. January 2010. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK44660/pdf/TOC.pdf.

- Dunstan DW, Howard B, Healy GN, et al. Too much sitting—A health hazard. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2012 Sep;97(3):368–376.

- Schuna JM, Johnson WD, Tudor-Locke C. Adult self-reported and objectively monitored physical activity and sedentary behavior: NHANES 2005–2006. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2013 Nov 11;10:126.

- Hamilton MT, Healy GN, Dunstan DW, et al. Too little exercise and too much sitting: Inactivity physiology and the need for new recommendations on sedentary behavior. Curr Cardiovasc Risk Rep. 2008 Jul;2(4):292–298.

- Tremblay MS, Colley RC, Saunders TJ, et al. Physiological and health implications of a sedentary lifestyle. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2010 Dec;35(6):725–740.

- Buman MP, Winkler EA, Kurka JM, et al. Reallocating time to sleep, sedentary behaviors, or active behaviors: Associations with cardiovascular disease risk biomarkers, NHANES 2005–2006. Am J Epidemiol. 2014 Feb 1;179(3):323–334.

- Wen CP, Wai JP, Tsai MK, et al. Minimal amount of exercise to prolong life: To walk, to run, or just mix it up? J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014 Aug 5;64(5):482–484.

- Tudor-Locke C, Craig CL, Aoyagi Y, et al. How many steps/day are enough? For older adults and special populations. Int J Behav Nutri Phys Act. 2011 Jul 28;8:80.

- Chau JY, Merom D, Grunseit A, et al. Temporal trends in non-occupational sedentary behaviours from Australian Time Use Surveys 1992, 1997 and 2006. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2012 Jun 19;9:76–83.