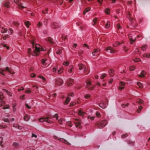

Blood smear in lupus erythematosus.

SPL / Science Source

A study published in the May issue of Arthritis Care & Research may be the first to examine the long-term outcomes of childhood-onset lupus, otherwise known as pediatric systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), a chronic, multisystem autoimmune disease with a highly variable clinical course. Previous studies examined cross-sectional views of damage accrued.

According to the Childhood Onset Lupus Education and Research Foundation, 1.5 million people in the U.S. have systemic lupus, and approximately 20% are children or teens. In addition, pediatric patients with lupus are more likely than adults to develop kidney disease, neurologic complications and hematologic disease.

Conducted by Canadian researchers, the May 2018 journal study followed 473 pediatric patients from the Hospital for Sick Children (SickKids) Paediatric Lupus Clinic in Toronto from their diagnosis as children into adulthood. Unlike previous studies, in which damage seemed to plateau among pediatric SLE patients, this study showed that damage continued to accrue throughout the observation period.

Of the 473 participants, 2% died and 14% were lost to follow-up. Earl Silverman, MD, FRCPC, a study co-author and staff rheumatologist at the Hospital for Sick Children, says the mean duration of follow-up was 5.63 years, with the longest being 26.3 years.

“In looking at childhood lupus, we know that as we follow patients, their prognosis can change over time,” Dr. Silverman says. “We were interested in looking at what happens to these patients in adulthood, [because] very little is known about this.”

Dr. Silverman says researchers sought to identify baseline factors that predict membership into different classes of disease activity. These factors included sex, (self-reported) ethnicity, age at diagnosis, pubertal status at diagnosis (yes/no), time period of diagnosis, number of ACR classification criteria met at diagnosis and life-threatening, major organ involvement.

The study found the most common form of organ damage was cataracts, which developed in 14% of the children, and avascular necrosis, seen in 10% of patients.

Dr. Silverman notes the primary outcome was the SLE International Collaborating Clinics/ACR (SLICC/ACR) Damage Index, a validated measure of irreversible damage in SLE.

“We found 13 cases of cardiovascular damage in 10 patients, including 11 cerebrovascular events and two myocardial infections,” he says. “The median age of cardiovascular damage was 16.8 years.”

Evaluating Treatment Options

Although prompt treatment for lupus is important, Dr. Silverman notes the care and treatment of children and teens with SLE is different than for adults. He says people who have SLE onset in childhood have a more severe disease presentation, have a more aggressive clinical course, require more medications and suffer more rapid damage accrual than adult-onset disease.

“Typically, lupus in children tends to be overtreated or undertreated,” Dr. Silverman says. “By examining different prognostic factors, we wanted to determine what patients might need less treatment and those who might require more aggressive treatment.”

Researchers also found the use of prednisone and immunosuppressives (particularly cyclophosphamide) were associated with an increase in damage; whereas, antimalarial use protected against organ damage. Dr. Silverman notes that researchers believe the association of immunosuppresives with increased damage likely reflects their use in patients whose condition was seen as more severe and does not show direct damage by these treatments.

The researchers hope once their research is validated in independent cohorts, it will help rheumatologists determine the best patient management strategies to reduce the risk of organ damage.

“We found antimalarial use from six months prior to a visit protected against an increase in damage, even in the face of high-dose prednisone and cyclophosphamide, which illustrated a window of protection,” Dr. Silverman says. “We were able to show the protective effects were continued six months after exposure, illustrating that in order to achieve sustained benefits, physicians need to encourage long-term adherence to antimalarials.”

Dr. Silverman noted that although the study had no surprises, it did validate the researchers’ clinical intuition. He says his team hopes to perform follow-up studies and believes their research can be reproduced in other cohorts.

“Some of the patients were followed for 20 years, but the median was five years, which emphasizes the need for future studies,” Dr. Silverman says. “We also found that Afro-Caribbean patients, who have been known to [suffer] more SLE damage, also have a higher damage trajectory that started early compared to Caucasians and Asians.”

Among other notable findings, the study found acute confusion, lupus headache or fever predicted a subsequent increase in the damage trajectory, and active SLE, independent of steroids, was identified as a risk factor for avascular necrosis.

Ultimately, the researchers hope once their research is validated in independent cohorts, it will help rheumatologists determine the best patient management strategies to reduce the risk of organ damage.

“For instance, [patients] destined to have disease refractory to current standards of treatment might be considered for newer therapies,” Dr. Silverman says. “And for those with low-grade disease activity, attention should be paid to continue closely monitoring their condition.”

Unlike rheumatoid arthritis, in which flares cause obvious symptoms, such as an increase in joint pain, joint swelling and fatigue, SLE can lead to silent flares detected only by ongoing bloodwork, says Dr. Silverman.

“There are currently no guidelines for how often SLE patients should be

tested, but doing bloodwork every three to four months at a minimum is a good baseline to prevent complications,” Dr. Silverman says.

Linda Childers is a health writer located in the San Francisco Bay Area.

References

1. Lim LSH, Pullenayegum E, Feldman BM, et al. From childhood to adulthood: Disease activity trajectories in childhood-onset systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2018 May;70(5):750–757.